Book review: Swamiji: An Early Disciple, Brahmananda Dasa, Remembers His Guru

By Vineet Chander (Venkata Bhatta Das) | Jan 08, 2015

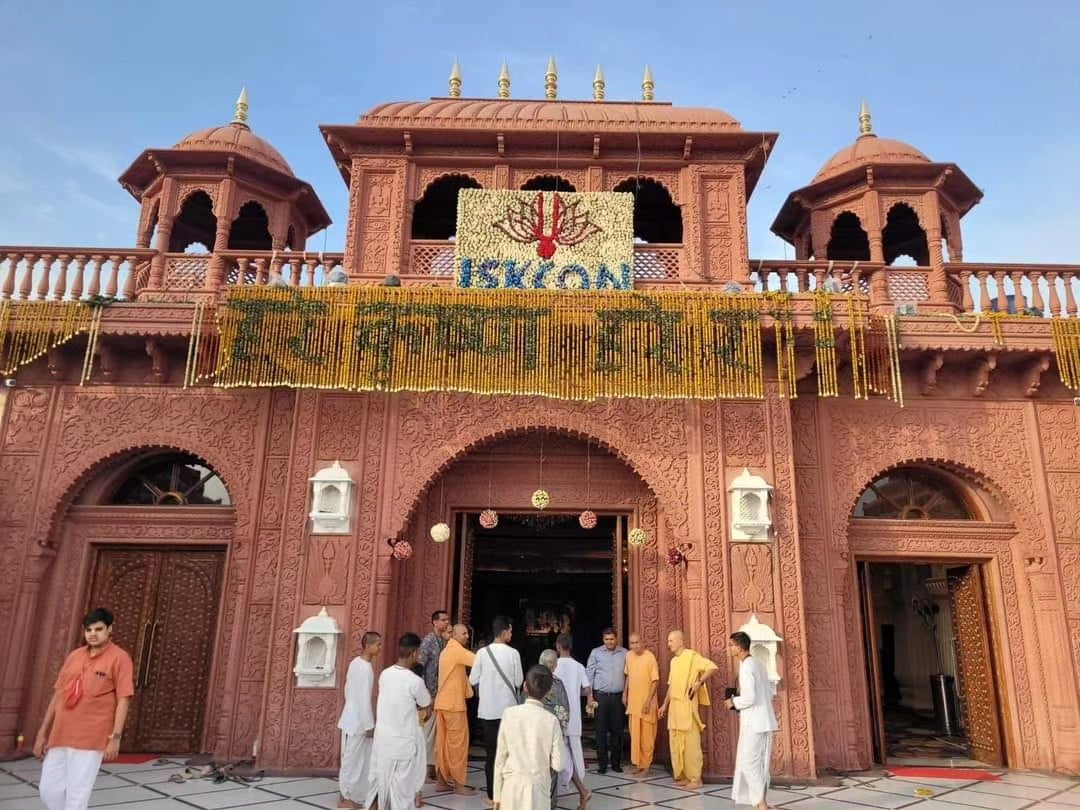

Swamiji by Steven J. Rosen is a recent and particularly delightful addition to the growing body of books recording the memories of direct disciples of Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the Hare Krishna movement (more formally the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, or ISKCON). These memoirs seek to supplement more formal hagiographies, such as the multi-volume ISKCON-commissioned biography of Prabhupada penned by Satsvarupa dasa Goswami. In Hare Krishna parlance, they are “nectar books”—devotional testimonies that are to be savored like a sweet dessert or an ambrosial elixir, rather than merely read.

Rosen (better known to fellow Krishna devotees as Satyaraja Das) presents us with a remarkable bit of nectar in Swamiji. The book, obviously drawn from thorough interviews and meticulous fact checking, shares the remembrances of Rosen’s friend Brahmananda Das. As one of Prabhupada’s first disciples, Brahmananda was an eyewitness to, and a participant in, the birth of a religious movement. Moreover, even among early disciples, he is a figure of singular importance. He was quite literally at the center of almost all of ISKCON’s “firsts”—he served as its first president; was one of its first sannyasis, or itinerant monks; played an instrumental role in facilitating its first major publications; was intimately involved in securing its first icon for worship; and so on and so forth. As the eminent scholar Dr. Thomas J. Hopkins writes in his foreword, “nobody apart from Bhaktivedanta himself was more of an insider” than Brahmananda. I concur with Dr. Hopkins that Rosen is owed a debt of gratitude for his putting such an important disciple’s memories to print.

Of course, we ought to commend Rosen for much more than just his wisdom in choosing to tell Brahmananda’s story. How he chooses to tell the story deserves recognition, as well. Let me just highlight a few of the book’s many strong points. The writing is crisp, engaging, and thoughtful—deep such that it warrants reflection, but light enough to make for excellent on-flight or bedside reading. Rosen writes the book so that his subject is intelligible to any reader (as he does with virtually all of his books), but also plays to a target audience—in this case, Krishna devotees, and perhaps sympathetic academics with a particular interest in ISKCON’s history, like Dr. Hopkins. Swamiji doesn’t seem particularly concerned with connecting with a wider mainstream readership; I will return to this a bit later in the review.

Another way in which Swamiji excels is in the book’s remarkable ability to convey the child-like sweetness and intimacy of Brahmananda’s relationship with his guru. This is particularly evident in Rosen’s recounting of Prabhupada’s stroke and convalescence. Readers are able to experience through this episode, in vivid detail, the love the Swami’s young disciples felt as they nursed their ailing master back to health. This heart-rending care is mirrored later in the book when Rosen recounts a car accident Brahmananda and Prabhupada suffered in Mauritius; the disciple flagged down a passing car and exclaimed that his “grandfather” had been injured and needed to be taken to the hospital. It is this side of the Prabhupada story—the loving grandfather and his devoted wards—that Rosen brings out so well in Swamiji.

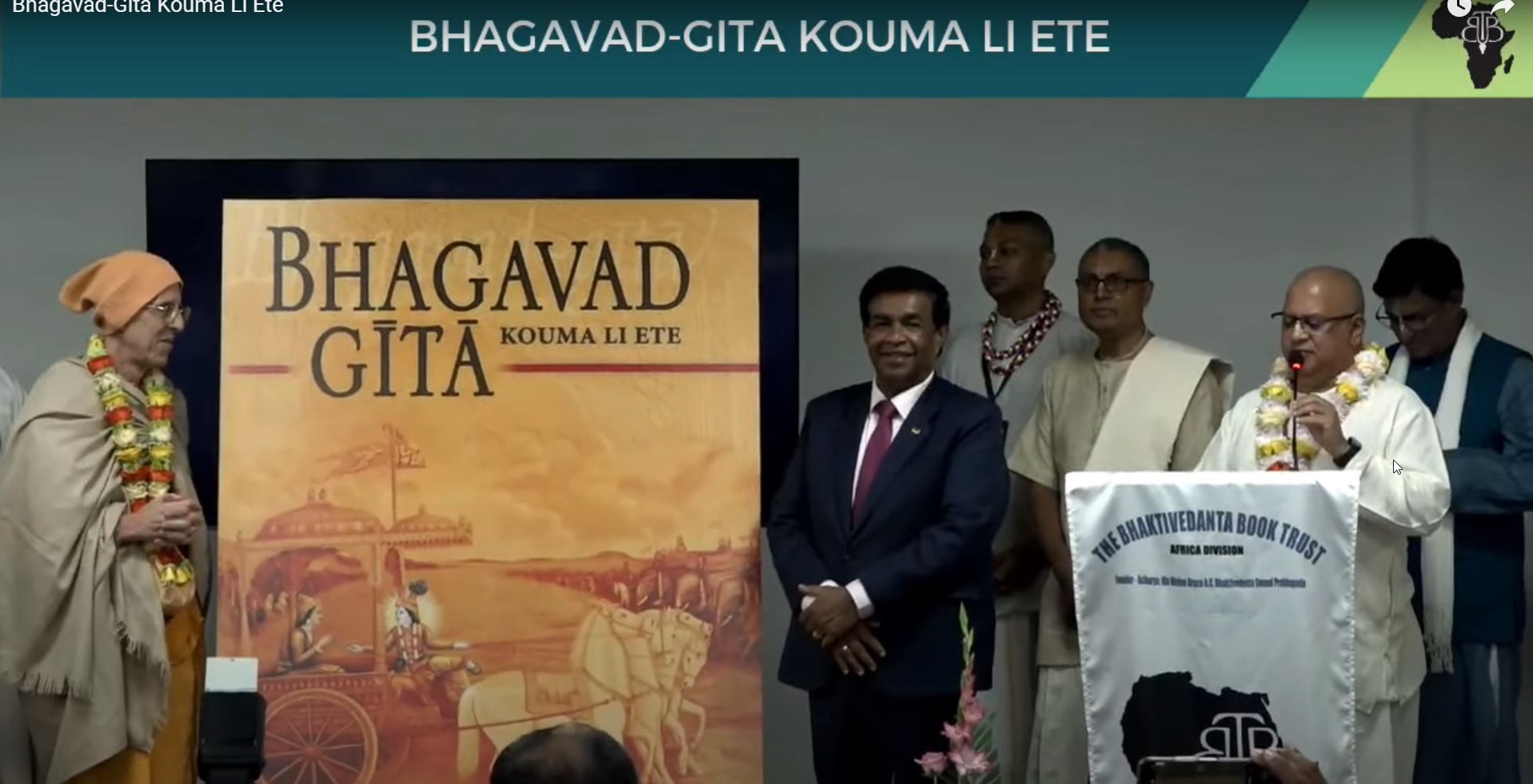

Similarly, Swamiji does a great job of evoking the “magic” of the Hare Krishna movement’s birth. Rosen tells a number of stories—some of which have not been recorded anywhere else—that proclaim the amazing, even miraculous, nature of the extraordinary episodes that marked these pioneering days. Brahmananda remembers, for instance, how a mysterious and unsolicited call from an Indian importer acquaintance resulted in ISKCON acquiring its first murti of Krishna. He also recalls the remarkable tale of how one of the biggest mainstream publishers in the world agreed to publish Prabhupada’s Bhagavad Gita translation, sight unseen—something so astounding that Rosen subtitles the episode “the Macmillan miracle.” Rather than spoil the surprise by giving away more details on either of these stories, suffice it to say that Brahmananda’s remembrances give us a fascinating glimpse into the “hand of Krishna” at work in his devotees’ lives. Rosen narrates these glimpses skillfully—relishing in their fantastical undertones while still maintaining their plausibility.

Rosen is to be commended for venturing into some controversial and darker territory, as well—he writes about Brahmananda’s role in a murky plot to undermine Prabhupada’s leadership of the movement. Nonetheless, I must confess that I found this to be the weakest part of the book; Rosen seems too inclined to “play it safe” in his description of the episode, preventing readers from making a strong enough emotional connection to it. He narrates how Brahmananda and a handful of his peers began to propound the unorthodox idea that Prabhupada was Krishna himself. The guru roundly condemned this as heresy and declared it to be part of a conspiracy designed to usurp the organization from him. Prabhupada dealt with the conspirators by sequestering them from the other devotees, stripping them of their ecclesiastic positions and financial support, and exiling them to the wilderness of the missionary field—in Brahmananda’s case, a field that included war-torn Pakistan. Rosen describes this all lucidly, but a bit too cautiously; he frames the controversy in abstract and philosophical terms, but veers away from exploring the emotional impact that it must have had on the relationship between master and disciple. Doubt, remorse, guilt, anger, despair—it would have been only natural for Brahmananda to have wrestled with these, but Swamiji doesn’t offer us a way to connect with him in them. As a result, readers—particularly those who might not already identify as Hare Krishna devotees—are deprived of a chance to relate to either Brahmananda or Prabhupada in their humanness.

Likewise, Swamiji does a good job drawing us into Brahmananda’s story, but “leaves us hanging” when it comes to his life today. At book’s end, he is depicted as a monk and globetrotting leader of the Hare Krishna movement; today, he leads a decidedly low-key (and, I imagine, more content) life as a layperson in Vrindaban, India. How did that come to pass? Let me be clear: I do not mean to suggest that Rosen ought to have written a salacious tell-all, detailing every challenge Brahmananda faced in the tumultuous decades following his guru’s death. But some efforts to “fill in the blanks”—perhaps in the afterword—might have served to close the loop on his story, and again helped readers to relate to this important devotee in a more personal way. In this regard, Rosen and Brahmananda might have followed the example set by a number of western Buddhist memoirists, who share their adventures as monastics but also candidly relay their eventual decision to leave that lifestyle and re-integrate with the world outside the monastery.

To be fair, my complaint is less a critique of Swamiji per se and more a lament at the lack of devotee-penned memoirs that might speak to a postmodern mainstream audience. To resonate with this audience, I think, would require the memoirist to share the fullness of his or her experiences as a devotee—a “mixed bag” of memories that would include the good with the bad, the doubts with the devotion, the salty with the sweet. There are now dozens of remembrances published by Prabhupada’s disciples waxing nostalgic about their time at the feet of the master. Meanwhile there are also a handful of books authored by former devotees, looking back at their time in the movement through a sharply critical lens—Nori Muster’s Betrayal of the Spirit is a particularly noteworthy example in this genre. What may be missing are the voices in the middle: devotees approaching the past with fondness and gratitude, but also willing to swap out some of the nostalgia for more critical (and self-critical) reflection. Thoughtful books like Swamiji move us closer to hearing from such voices, but also remind us that we’re not quite there yet.