The Economy in Three Modes – Part II

By Ravindra Svarupa Dasa | Jun 28, 2009

Knowledge of the three modes (guṇa–traya) proves to be fruitful on a variety of levels. The principles that offer insight into the working of individuals also illuminate the characteristics of entire cultures or civilizations. PrabhupÄda demonstrates this application in a comment on the GÄ«tÄ: “Modern civilization is considered to be advanced in the standard of the mode of passion. Formerly, the advanced condition was considered to be in the mode of goodness.”

PrabhupÄda’s remark provides us with an illuminating and useful way to comprehend recent western history.

We can clearly recognize the shift from the standard of goodness to that of passion in the great historical transformation from an agrarian economy to an industrial economy—or “modernization” as it is called.

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century was a watershed in the process, but neither the beginning nor the end of it. Industrialization has kept on going: Agriculture did not become fully industrialized until after World War II, when traditional family farms became replaced by huge “factory farms,” agri-businesses controlled by multinational corporations.

Reviewing Michael Pollan’s recent documentary “Food, Inc.” Andrew O’Hehir notes

We’ve got the fact that, as Pollan puts it, the production of food has changed more in the last 50 years than it did in the previous 10,000. With the massive application of fertilizers, pesticides and economies of scale after World War II, raising crops and animals for food ceased to be a rural lifestyle based on many small farmers and ranchers, and rapidly became a heavily mechanized (and lightly regulated) industry dominated by a handful of big companies who run on low-wage labor.

Most recently, computer technology has been transforming “white collar” occupations—including those of medicine and education—into factory-style assembly-line labor.

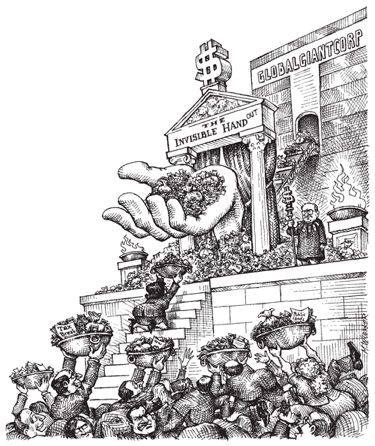

The rajo–guṇa gospel of “progress” has converted nearly the whole world, and everyone worships at the feet of Economic Development.

What can we expect of all this progress? The answer is not in dispute: rajasas tu phalaṠduḥkham. The fruit of the mode of passion is suffering.

Our refugees from the Wall Street storm, reflecting on their travail, call on the President to lead us away from a culture of greed and avarice, of “more is better,” in effect to lead us from passion to goodness. Yet the great government bail-out of financial firms seems mostly to have prompted an additional frenzy of greed.

In terms of our science, we recognize that modernity is a hypertrophy, a monstrous overdevelopment, of rajo–guṇa and the predicted, inevitable outcome—misery—is arriving big time, on multiple fronts: the financial storm crashing around is just the leading edge of the mother of all hurricanes on the way: the global climate crisis.

The reactions to the misery engendered by rajo–guṇa will be in the three modes also. As often happens, Lewis and Cohan are at least attracted to sattva–guṇa, and the Lewis Family Farm, “devoted to the principles of organic sustainable agriculture” seems a laudable attempt to return to a purer, more sattvic way of life.

Unfortunately, he has some way to go. Those who know the science of the guṇas doubt that much will be gained by exchange of this:

Exploiting the Bull Market for Money—Rajo–guna

For this:

Exploiting the Hereford Bull for Beef—Tamo–guna

Knowledge of the three guṇas is greatly needed to help us deal effectively with our overwhelming crisis, the ever-growing global misery engendered by the hypertrophy of the mode of passion.

Whenever rajo–guṇa yields its harvest of suffering and misery on which we feast, we undergo the typical reactions to such a diet—for instance, rage and its internalize form known as depression, sedation by low- or high-tech drugs, escape into illusions and delusions—such reactions convey us into tamo–guṇa.

Yet there is also the chance that with a little help we can also elevate ourselves to goodness.

PrabhupÄda asserts that we have choices.

Here in his account of struggles of the individual spiritual self (the ÄtmÄ) with the modes, PrabhupÄda describes our options:

When a living entity comes in contact with the material creation, his eternal love for Kṛṣṇa is transformed into lust, in association with the mode of passion. Or, in other words, the sense of love of God becomes transformed into lust, as milk in contact with sour tamarind is transformed into yogurt. Then again, when lust is unsatisfied, it turns into wrath; wrath is transformed into illusion, and illusion continues the material existence. Therefore, lust is the greatest enemy of the living entity, and it is lust only which induces the pure living entity to remain entangled in the material world. Wrath is the manifestation of the mode of ignorance; these modes exhibit themselves as wrath and other corollaries. If, therefore, the mode of passion, instead of being degraded into the mode of ignorance, is elevated to the mode of goodness by the prescribed method of living and acting, then one can be saved from the degradation of wrath by spiritual attachment.

(The word “lust” here—kÄma in Sanskrit—denotes the strong desire to enjoy the pleasures of the sense. KÄma is not limited to sexual desire, although sex, as Freud said, “is the prototype of all pleasure.”)

Most of us can see everywhere the increase in the effect of the mode of ignorance. Mental disturbances proliferate all around us. In America, one out of four adults suffer in a given year from a diagnosable mental disorder, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Look it up—or just turn on a television or take a walk through the city streets. . . . Based on a 2001 study, the World Health Organization predicted that by 2020 mental illness would become the second leading cause of death and disability in the world.

Politically, the increase in tamo–guṇa can be seen in the rise of social or cultural rage, resentment, panic, and despair. The rant has become a favorite form of political discourse (check out “Rant of the Year”), with a concomitant rise of ideologically motivated violence.

The economy in the mode of ignorance is chronically depressed (and depressing), and prosperity turns out to be illusory, producing fortunes as insubstantial as the airy nothing of day-dreams, made only of “bubbles.” Livelihoods increasing depend on the black market or underground economy. Prisons, mental facilities, addiction recovery centers, and similar institutions that care for those overwhelmed by tamo–guṇa become a vital element of the visible economy.

Although those committed to the culture and economy of rajo–guṇa see and fear the increase of tamo–guṇa, they do not know how to deal with it effectively. This is because their own solution to the problems caused by rajo–guṇa is simply more rajo–guṇa.

In dealing with mental illness, for example, it rarely occurs to them that if many people are disturbed it is because the conditions of their lives are in fact disturbing. If they should recognize this, they have no idea of how to deal with it; or if they do have some inkling, they think the solution “impracticable.” They rely on the mode of passion, and put their hopes in “big pharma.”

I remember well the first great oil shock that rocked the country in 1973. Many saw it as a harbinger of things to come, especially in light of a study published the previous year, which argued that in view of the earth’s finite resources, we were approaching The Limits to Growth. The book sold thirty million copies.

People began to give serious consideration to proposals that we should live in ways that had many features of what would be, in our terms, an economy in the mode of goodness: local self-sufficiency in food and energy (features of an agrarian economy), shift to a largely vegetarian diet, employ appropriate technology, and so on.

The idea of limits to growth is anathema to those in the mode of passion. I remember receiving several issues of a newsletter, put out by some consortium of large energy corporations, assailing the idea of limits to growth as sacrilege against Progress itself. Whatever problems human ingenuity creates, that same ingenuity solves. When the “cavemen” learned to control fire, and found the flames of their hearths filled their shelters with smoke, did they abandon fire? No! That is not the human way! They “advanced” by devising further technology—in this case, chimneys. The problems of technology will be solved by more technology.

Now that further technology threatens apocalyptic catastrophe produced global climatic changes, scientists are busy developing ingenious technological fixes. The cavemen now must erect a chimney on the earth. Well, not that, exactly.

Here’s one plan: We have already seen that erupting volcanoes produce global temperature drops by pouring vast amount of sun-blocking sulfur dioxide into the air. We engineer the same effect, thus counteracting the temperature increase from greenhouse gases. Imagine, then, an armada of 1,500 zeppelins hovering at 65,000 feet, each one studded with nozzles that continuously spew a mist of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere. Flexible hoses trail from each airships like strands of vermicelli from an uplifted fork; the sulfur dioxide aerosol is pumped aloft through these conduits from production plants on the ground at a rate of ten kilos per second. This process goes on 24/7, no end in sight.

Graeme Wood surveys a number of such breathtaking geo-engineering plans under development in his article “Moving Heaven and Earth” in the latest issue of The Atlantic.

Wood is concerned to emphasize the great risk such solutions pose. We are messing with our entire ecology, and there is a distinct danger of unforeseen consequences on a catastrophic scale. If we employ the sulfur dioxide or other sun-blocking schemes—because reduction of greenhouse gas emissions proves politically or economically unworkable—then those gases will continue to build up in the atmosphere. If, for any reason, one of these projects stops, then the accumulated atmospheric carbon could produce a sudden and drastic temperature rise, with calamitous results.

Wood notes that these schemes are considerably cheaper than the cost of sufficiently reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Estimates that geo-engineering could completely reverse human caused climate change for $100 billion—and some say for much less. Reducing emission will cost an estimated one trillion dollars, yearly.

The low cost of such schemes makes them more attractive. And, in fact, it brings some of them within the scope of unilateral action by even a poor nation—or of a single very rich individual. Those who worry about these things dread the emergence of a hypothetical “Greenfinger,” the environmental cognate of Goldfinger, the mega-villain of the James Bond sagas.

Wood, in fact, hopes that these geo-engineering solutions are so frightening and affordable that these very features may prompt—through sheer terror—a serious effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Yet the possibility of geo-engineering would remain, lurking in the near shadows, poised to pounce like the monster in a horror movie, the price of our failure.

It is typical for those controlled by rajo–guṇa to try to assuage the resulting misery by means of the very mode that produced it. At best, these efforts can no more than retard the fruition of misery, and the delay only amplifies the suffering when it arrives with tamo–guṇa in its train, smothering the earth.

One thing is sure: We are soon to be instructed and entertained by some of the several dozen eco-disaster-horror-thriller novels and screenplays now filling up hard drives across the land. Greenfinger! Who could resist?

Wood’s overview of geo-engineering plans provides us with a textbook-worthy study of rajo–guṇa in large scale action. Be very scared.

Under these circumstances it is encouraging to see a widespread increase in attraction for what is, in effect, the mode of goodness. Impelled by danger and dire need, Wordsworth’s “plain living and high thinking,” disappearing in his own time, awaits a revival.

Here the science of the modes has a major contribution to make: how to free the human heart from the control of rajas and tamas and situate it in sattva. Such an effort attacks our social, political, and environmental problems at their very root. This treatment of the disease of the heart, including “the prescribed method of living and acting,” is proven efficacious: PrabhupÄda’s ISKCON may be seen as a kind of pilot program in this regard. Where the treatment has been properly applied, it has worked.

Where the treatment has failed of proper application, it should be implemented once more, with greater care. This is an urgent matter. In our global emergency, any who undertake a renewed and revivified effort to elevate themselves to goodness by the “proscribed methods” will bring inestimable benefit not only to themselves, but also to all humanity—more—to all living beings on earth.

The clock is ticking.