A Voice in the Public Debate

By Sesa Dasa | Июн 06, 2009

Something old or something new, this question lies at the center of a friendly rivalry between me and my friends from England. Americans loves firsts. The first automobile, the first airplane flight, the first man on the moon, America is a nation built on firsts. England on the other hand is a country that revels in maintaining the old. St. Michael’s Tower in Oxford dates from 1040.

My friends point to their deep roots as a measure of the value of their 1000+ year culture and civilization. I point to the incredible diversity of the American experience that, to our credit, and admittedly sometimes even to our detriment, 230 years into its existence continues to produce firsts.

Media legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin recently wrote about firsts and American diversity in The New Yorker magazine when covering the most recent first, President Obama’s (a notable first himself) nomination of Sonia Sotomayor to the United States Supreme Court, “Sixth Catholic. Second woman. Third New Yorker (First from the Bronx, Ruth Bader Ginsburg hails from Brooklyn, Antonin Scalia from Queens.) First Hispanic.”

Toobin adds, “It’s understandable and appropriate to examine Sonia Sotomayor’s nomination to the Supreme Court according to the customary demographic designations.” OK, fair enough, just as everyone demographic designation can be placed into the public debate, and those of all demographic designations deserve a right to participate in the public debate, to have a voice in the public debate, I say the Hare Krishnas do too.

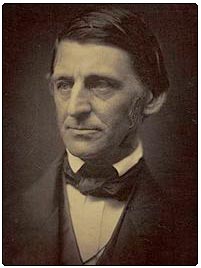

For those who would be skeptical about giving a voice to the Hare Krishnas in the public debate, let me point out another interesting American first. The first voice given to Bhagavad-gita, the mainstay of the Hare Krishnas, in American public debate dates back 180 years to the American Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

Dr. Ashton Nichols, an English professor at Dickinson College, describes Transcendentalism as an American attempt to produce a new philosophy that would serve a new nation. Although drawn from various intellectual traditions, Transcendentalism was to be a first, something uniquely American. Of Emerson Professor Nichols says, “Emerson wanted to shrug off the shackles of European society and stake a prophetic claim for American culture.”

A major component of Transcendentalism was found in the traditional writings of Eastern religions. Professor Nichols explains, “Emerson was reading Asian sacred and historical writings long before most Americans knew they existed, especially those from India. The texts included the Bhagavad-Gita, the Vedas, and the Laws of Manu. Thoreau read these works and reported on their immediate influence on him: ‘In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial.’ ”

American Transcendentalism was meant to be more than an intellectual pastime. It was in part a response to the socio-political landscape of the emerging American nation, and the ideas were decidedly social in their aim. The Web of American Transcendentalism site explains the kind of America that Emerson was responding to: politically stagnant as neither major party supported significant changes; the rights of minorities and women at question; and issues about ethical values and economic wealth. (NOTE: Seems that despite our culture of firsts our problems remain the same.) The response, Emerson believed; lie in a personal version of spiritual life.

As Hare Krishnas, students of Bhagavad-gita, we can clearly recognize this text’s influence on tenants of American Transcendentalism as described by Professor Nichols: “1. The essential idea was that a portion or spark of divinity resided in each individual and could be accessed by a transcendent self; 2. The idea of the self gained a new value and authority because of the role played by this inner voice; 3. The individual soul could be identified with the Over-Soul, or the world soul, or perhaps even “God;” 4. The details of our own experiences are a microcosm of overall existence; 5. The world needed to be understood in spiritual terms rather than through reductive materialism.”

Professor Nichols concludes, “Out of the Emersonian idea of America emerged a wide range of related ideas, a new view of American psyche or soul arose, a soul that is expansive and sensitive, delicate in its observational abilities yet powerful in its potential to bring about social change.” Hare Krishnas may not be the first, but do indeed deliver the same message of social change through spiritual discipline today.

Here’s where I have to give credit to my friends from England and their insistence on maintaining the old. There is great value in the wisdom of the ancients. The value of good ideas is that they transcend time and thus remain always relevant. Bhagavad-gita itself speaks of truth in this way, “Those who are seers of the truth have concluded that of the nonexistent there is no endurance and of the eternal there is no change. This they have concluded by studying the nature of both.” BG 2:16. Seems that the old and new actually work more effectively together than as rivals.

So, the next time issues of public debate come up, no need to feel shy about being a Hare Krishna and shrink away, take heart and enrich the debate with a true American original, the philosophy of Bhagavad-gita. It’s been done before.

Hmm”¦I wonder if Judge Sotomayor has ever issued a ruling on a sankirtan book distribution case?