Ancient Monument to the Soul Discovered in Turkey

By John Noble Wilford | Ноя 22, 2008

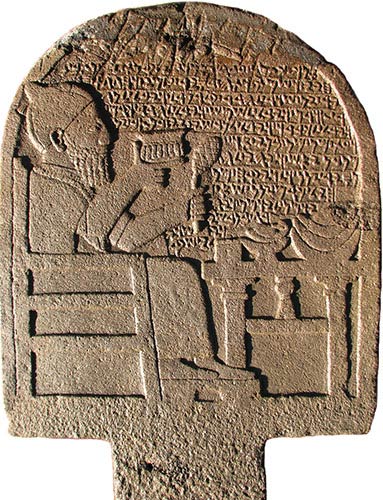

In a mountainous kingdom in what is now southeastern Turkey, there lived in the eighth century B.C. a royal official, Kuttamuwa, who oversaw the completion of an inscribed stone monument, or stele, to be erected upon his death. The words instructed mourners to commemorate his life and afterlife with feasts “for my soul that is in this stele.”

University of Chicago archaeologists who made the discovery last summer in ruins of a walled city near the Syrian border said the stele provided the first written evidence that the people in this region held to the religious concept of the soul apart from the body. By contrast, Semitic contemporaries, including the Israelites, believed that the body and soul were inseparable, which for them made cremation unthinkable, as noted in the Bible.

Circumstantial evidence, archaeologists said, indicated that the people at Sam’al, the ancient city, practiced cremation. The site is known today as Zincirli (pronounced ZIN-jeer-lee).

Other scholars said the find could lead to important insights into the dynamics of cultural contact and exchange in the borderlands of antiquity where Indo-European and Semitic people interacted in the Iron Age.

The official’s name, for example, is Indo-European: no surprise, as previous investigations there had turned up names and writing in the Luwian language from the north. But the stele also bears southern influences. The writing is in a script derived from the Phoenician alphabet and a Semitic language that appears to be an archaic variant of Aramaic.

The discovery and its implications were described last week in interviews with archaeologists and a linguist at the University of Chicago, who excavated and translated the inscription.

“Normally, in the Semitic cultures, the soul of a person, their vital essence, adheres to the bones of the deceased,” said David Schloen, an archaeologist at the university’s Oriental Institute and director of the excavations. “But here we have a culture that believed the soul is not in the corpse but has been transferred to the mortuary stone.”

A translation of the inscription by Dennis Pardee, a professor of Near Eastern languages and civilization at Chicago, reads in part: “I, Kuttamuwa, servant of [the king] Panamuwa, am the one who oversaw the production of this stele for myself while still living. I placed it in an eternal chamber [?] and established a feast at this chamber: a bull for [the god] Hadad, a ram for [the god] Shamash and a ram for my soul that is in this stele.”

Dr. Pardee said the word used for soul, nabsh, was Aramaic, a language spoken throughout northern Syria and parts of Mesopotamia in the eighth century. But the inscription seemed to be a previously unrecognized dialect. In Hebrew, a related language, the word for soul is nefesh.

In addition to the writing, a pictorial scene chiseled into the well-preserved stele depicts the culture’s view of the afterlife. A bearded man wearing a tasseled cap, presumably Kuttamuwa, raises a cup of wine and sits before a table laden with food, bread and roast duck in a stone bowl.

In other societies of the region, scholars say, this was an invitation to bring customary offerings of food and drink to the tomb of the deceased. Here family and descendants supposedly feasted before a stone slab in a kind of chapel. Archaeologists have found no traces there of a tomb or bodily remains.

Joseph Wegner, an Egyptologist at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the research, said cult offerings to the dead were common in the Middle East, but not the idea of a soul separate from the body — except in Egypt.

In ancient Egypt, Dr. Wegner noted, the human entity has separate components. The body is important, and the elite went to great expense to mummify and entomb it for eternity. In death, though, a life force or spirit known as ka was immortal, and a soul known as ba, which was linked to personal attributes, fled the body after death.

Dr. Wegner said the concept of a soul held by the people at Sam’al “sounds vaguely Egyptian in its nature.” But there was nothing in history or archaeology, he added, to suggest that the Egyptian civilization had a direct influence on this border kingdom.

Other scholars are expected to weigh in after Dr. Schloen and Dr. Pardee describe their findings later this week in Boston at meetings of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the Society of Biblical Literature.

Lawrence E. Stager, an archaeologist at Harvard who excavates in Israel, said that from what he had learned so far the stele illustrated “to a great degree the mixed cultural heritage in the region at that time” and was likely to prompt “new and exciting discoveries in years to come.”

Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute, said the stele was a “rare and most informative discovery in having written evidence together with artistic and archaeological evidence from the Iron Age.”

The 800-pound basalt stele, three feet tall and two feet wide, was found in the third season of excavations at Zincirli by the Neubauer Expedition of the Oriental Institute. The work is expected to continue for seven more years, supported in large part by the Neubauer Family Foundation of Chicago.

The site, near the town of Islahiye in Gaziantep province, was controlled at one time by the Hittite Empire in central Turkey, then became the capital of a small independent kingdom. In the eighth century, the city was still the seat of kings, including Panamuwa, but they were by then apparently subservient to the Assyrian Empire. After that empire’s collapse, the city’s fortunes declined, and the place was abandoned late in the seventh century.

A German expedition, from 1888 to 1902, was the first to explore the city’s past. It uncovered thick city walls of stone and mud brick and monumental gates lined with sculpture and inscriptions. These provided the first direct evidence of Indo-European influence on the kingdom.

After the Germans suspended operations, the ruins lay unworked until the Chicago team began digging in 2006, concentrating on the city beyond the central citadel, which had been the focus of the German research. Much of the 100-acre site has now been mapped by remote-sensing magnetic technology capable of detecting buried structures.

This summer, on July 21, workers excavating what appeared to be a large dwelling came upon the rounded top of the stele and saw the first line of the inscription. Dr. Schloen and Amir Fink, a doctoral student in archaeology at Tel Aviv University, bent over to read.

Almost immediately, they and others on the team recognized that the words were Semitic and the name of the king was familiar; it had appeared in the inscriptions found by the Germans. As the entire stele was exposed, Dr. Schloen said, the team made a rough translation, and this was later completed and refined by Dr. Pardee.

Then the archaeologists examined more closely every aspect of the small, square room in which the stele stood in a corner by a stone wall. Fragments of offering bowls to the type depicted in the stele were on the floor. Remains of two bread ovens were found.

“Our best guess is that this was originally a kitchen annexed to a larger dwelling,” Dr. Schloen said. “The room was remodeled as a shrine or chapel — a mortuary chapel for Kuttamuwa, probably in his own home.”

They found no signs of a burial in the city’s ruins. At other ancient sites on the Turkish-Syrian border, cremation urns have been dated to the same period. So the archaeologists surmised that cremation was also practiced at Sam’al.

Dr. Stager of Harvard said the evidence so far, the spread of languages and especially the writing on stone about a royal official’s soul reflected the give-and-take of mixed cultures, part Indo-European, part Semitic, at a borderland in antiquity.