Autobiographical Writing in Vaishnavism

By Chaitanya Charan Das | Июн 20, 2014

As an author, I am often asked questions about the different kinds of writing that devotees can engage in. One genre whose authenticity comes up for questioning is the genre of autobiographical writing in Vaishnavism. The most prominent example of this kind of writing is The Journey Home by Radhanath Swami, but several other devotees have also written or are writing their memoirs or autobiographies e.g.Diary of a Traveling Monk by Indradyumna Swami, Lost and Found in India by Braja Sevaki Devi Dasi and Urban Monk by Gadadhar Pandit Das.

In this article, I address common questions about autobiographical writing.

Are there any precedents for this kind of writing in Vaishnavism?

Yes, there are many.

Some examples of sharing one’s own story of spiritual evolution to encourage others on the path of spiritual evolution are:

1. In the Bhagavatam (1.4 and 1.5), Narada Muni shares his own story with Vyasadeva

2. In the Mahabharata (Vana Parva), Marakandeya Rishi shares his story with the Pandavas, Narada Muni and even Krishna himself.

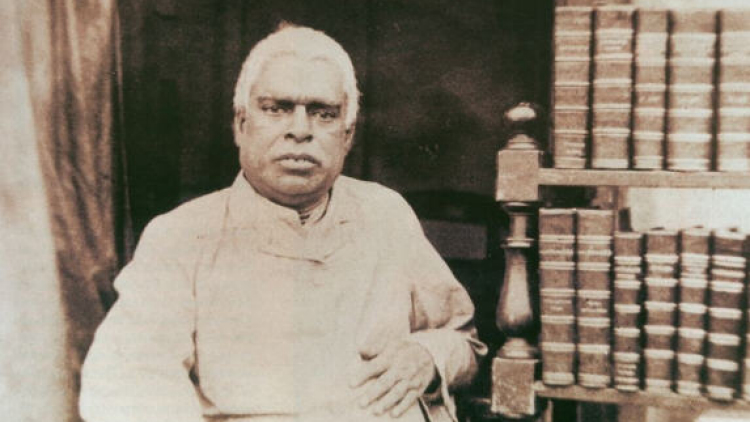

3. In the Gaudiya tradition, Bhaktivinoda Thakura wrote his Sva-likhita Jivani, a significant portion of which deals with his pre-devotional and non-devotional life.

4. In ISKCON’s official magazine, Back to Godhead, Srila Prabhupada encouraged devotees to share their stories in the feature “How I came to Krishna consciousness.”

Эта scriptural examples refer to great souls. Today’s devotees are not on their level, so how can the example of those souls be relevant?

Then whose examples would be relevant? Scriptural precedents of neophyte devotees? That raises the obvious question: would scripture record the example of some neophyte seeker who never rose to the level of becoming exalted? And even if somehow scripture did contain such an example, that example would be subject to dismissal with the charge: this was just a neophyte devotee and so was not an example to be followed.

So the net reasoning becomes: the advanced devotee is too advanced to be an example for us and the neophyte devotee is too neophyte to be an example for us. Such an argument is a lose-lose discussion, something like a rigged toss: Heads I win; tails you lose. Does that sound reasonable?

While scripture cautions us against imitating great souls, that caution is primarily when those souls do something against standard scriptural moral or spiritual principles eg. Shiva drinking bhang and Krishna dancing with the gopis. But as a matter of general principle, scripture tells us that the behaviour of great souls is what we have to follow e.g. Bhagavad-gita 3.21 yad yad acharati shreshtas … and Mahabharata Vana Parva 313.117 mahajano yena gatah sa panthah..

So unless scripture gives a specific caveat against doing something that the great souls have done, we can reasonably and safely consider scriptural precedents as examples to be emulated. While emulating their example, we don’t claim equality in spiritual stature with those great souls; we simply gain authorization for following in their footsteps, while acknowledging that our footsteps are lilliputian as compared to their giant footsteps.

Would such autobiographical books focus on the author and not convey the essence of Krishna consciousness?

That’s a possibility, but it’s by no means an inevitability.

Without a clearly stated and universally accepted definition of what comprises the essence, this charge is vague and insubstantial. To understand what the essence is, ISKCON devotees can rely primarily on the books of Srila Prabhupada. Let’s consider the example of The Journey Home. It talks about the difference between the body and the soul, the chanting of the holy names including specifically the Hare Krishna mahamantra, the superiority of bhakti-yoga over other forms of yoga and indeed over other forms of sadhana, the four regulative principles, Krishna as the sweetest manifestation of divinity higher than the impersonal brahman, the supreme charm of Vraja and the unparalleled compassion of the pure devotee, Srila Prabhupada. Anyone who has studied the teachings of Srila Prabhupada can easily recognize that these are the essence of the message that he gave to the world through his books.

Srila Prabhupada was resourceful in using outreach strategies that could ensure that Krishna’s message reached the world. Thus, whereas his spiritual master’s Western outreach was centered on the book “Sri Krishna Chaitanya” by Nishikant Sanyal, he chose to center his own outreach on the Bhagavad Gita. And he encouraged his followers to be similarly resourceful: to present the message he gave in the language of the people. Thus, for example, he asked devotee-scientists to present our philosophy in scientific language. And he approved wholeheartedly books such as “The Scientific Basis of Krishna consciousness” by Dr T D Singh (Bhakti Swarupa Damodar Maharaj) – and even wanted that book to be distributed vigorously. If one is obsessed with imagining that the essence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism is something esoteric, then this book would fall far short of such an essence: it focused primarily on one point – the existence and intelligence of God, Krishna, as the Supreme Scientist. In fact, in terms of coverage of essential themes of Krishna consciousness, Journey Home would score far higher than The Scientific Basis of Krishna Consciousness. This comparison is not meant in any way to minimize the latter book, but simply to point out that books based on contextual outreach strategies have been recommended and appreciated by our founder-acharya.

If one neglects this strategic dynamism demonstrated by our founder-acharya and stays locked in some frozen definition of the essence of Krishna consciousness, then one may end up committing offenses to many of Prabhupada’s learned and dedicated followers, who by their books have brought intellectual respectability to our tradition amidst the contemporary intellectual ethos. Some such books are Searching for Vedic India by Devamrita Maharaj, Mechanistic and Non-mechansitic Science by Sadaputa Prabhu and Деволюция человека by Drutakarma Prabhu. What to speak of offending venerable Prabhupada’s followers, one may even end up offending Prabhupada himself, because some of his books such as “Easy Journey to Other Planets” could be accused of not conveying the core truths of Krishna consciousness.

Wouldn’t such writing be a form of self-glorification that is opposite to the principles of bhakti?

Yes, it’s possible. But writing autobiographically doesn’t necessarily have to be self-glorificatory. In fact, when an author uses an autobiography as a vehicle to go on an ego trip, such autobiographies rarely become popular, even in the mainstream culture – hardly anyone likes an egotist. To be done effectively, autobiographical writing is a delicate and elusive skill that has to be learnt by finding. developing and sticking to a non-bragging voice.

Moreover, the essential principle of bhakti is neither self-glorification nor self-condemnation, but Krishna-glorification – and doing whatever is required for that.

The Mahabharata on one had condemns self-glorification as poison in the Karna Parva and on the other hand contains many instances of self-glorification by even virtuous characters, whenever the context calls for it. For example, Arjuna praises his own prowess when Yudhisthira asks him in the Bhishma Parva how quickly he can defeat the Kaurava forces; when Krishna cautions him in the Drona Parva that reaching Jayadratha on the fourteenth day would be a near-impossible task; and when (during the same incident in the Karna Parva that contains the condemnation of self-glorification) Arjuna assures Yudhisthira that he will soon slay Karna.

What to speak of the Mahabharata, even the amala-purana, the Bhagavatam contains several instances of self-glorification such as when Bhishma calls himself a pure devotee (1.9.22: ekanta bhakteshu).

The purpose of a devotee’s speech is neither self-glorification nor self-vilification, but Krishna-glorification. If Krishna’s purpose can be served by glorifying one’s own abilities so as to raise the morale of others in Krishna’s service (as is done by Arjuna and Bhishma), then self-glorification can also be used according to the principle of yukta-vairagya.

What is the need for this kind of autobiographical writing?

Because it has special authenticity in the contemporary cultural-intellectual ethos known as post-modernism.

In modern times (which are now considered outdated in the West), people there had faith in reason and science, which they considered as reliable means to certain knowledge. Prior to modern times, people had faith in revelation and scripture, but that faith was assaulted by science which apparently showed certain mistakes in the biblical scriptures. However, science didn’t reign on the human intellect for long; the influential works of historians of science like Thomas Kuhn have shown how science is not objective and how scientific theories are formulated, popularized and accepted based on the prevailing cultural and intellectual biases. Consequently, people in today’s post-modern times have faith neither in science nor in scripture as a reliable source of knowledge; they view with deep suspicion any source of knowledge that claims to be absolute. They consider all claims to final, indisputable knowledge as flawed and base their lives solely on experience, and so consider as authentic those teachers who speak based not on dogma but on experience. The enduring popularity of “Autobiography of a Yogi” is a testimony to this attractiveness of experiential spirituality. Many Mayavadis, Buddhists and Christians have popularized their philosophy by presenting it according to post-modern sensibilities, but not many people have done the same for Gaudiya Vaishnavism. In fact, the post-modernist fascination with experiential spirituality opens a great opportunity for us to share Krishna consciousness, because bhakti-yoga is highly experiential; it gives direct perception of the self by realization (pratyakshavagamam, Bhagavad-gita 9.2). Acknowledging this experiential potency of bhakti, Sanatana Goswami enthrones experience as the highest of all pramanas (ways of acquiring knowledge).

So sharing our experiences in our search for bhakti and the practice of bhakti enables us to tap a hitherto untapped opportunity to share Krishna consciousness opened by post-modernism. Through this genre, we can get around the post-modernist phobia towards value judgments and exclusivist ideologies, and skillfully and sensitively assist people to gain appreciation for the bhakti core of Krishna consciousness.