Bhaktivedanta Manor Bans Tallow Note, Sparks Debate

By Madhava Smullen | Дек 09, 2016

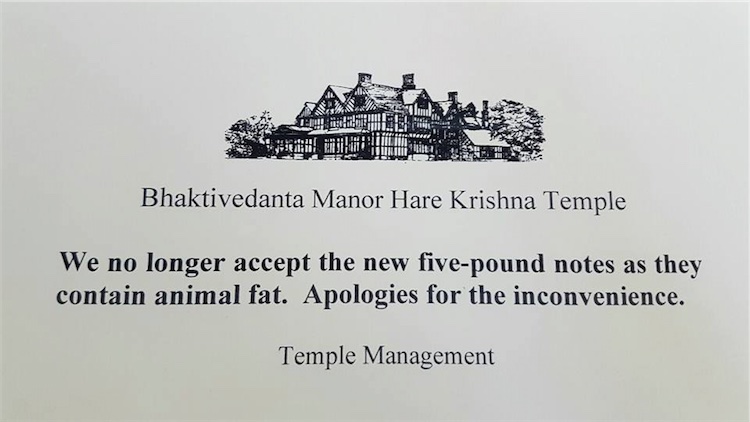

Bhaktivedanta Manor, the largest ISKCON temple in the UK, has stopped accepting a new five pound note that contains traces of tallow, made with animal fat like mutton and beef.

Many devotees support the move. Many others, however – while agreeing with the principle that there should not be meat fat in currency we all have to use – have issues with the practicality and even the philosophical grounding in actually banning it.

Therefore, other ISKCON temples in the UK have chosen not to ban the note.

The issue has also opened up a wider discussion in ISKCON about how to navigate a world where animal products are in so many other everyday things we use.

Bhaktivedanta Manor is not accepting the new fiver in its shop, bakery, or as donations to the Deities. “Our ethos is not to harm animals,” managing director Gauri Das explained to the BBC. “It’s problematic for us because we’re implicated in the process. So it’s immediately become a matter of concern for our community.”

The Manor’s main meditation in making the decision, says communications director Radha Mohan Das, was that otherwise people would be walking into the temple room, taking darshan of Radha Gokulananda, and putting a note in the donation box in front of the Deities that we all know has beef in it.

Bhaktivedanta Manor is not alone in making the decision. When the news came out, social media exploded with vegetarians, vegans and animal lovers expressing their frustration. The Rainbow Vegetarian Café in Cambridge refused to accept the notes, saying they were “repulsive.”

At least two Hindu temples also urged worshippers not to give charitable donations with the new £5, including Shree Sanatan Mandir, one of the largest Hindu temples in Leicester. And on its website, the National Council of Hindu Temples UK said the note incorporated substances “derived from acts of violence” and that “we would not want to come into contact with it.”

Meanwhile an online petition stated the new notes were “unacceptable to millions of vegans, vegetarians, Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and others in the U.K.,” and said, “We demand that you cease to use animal products in the production of currency that we have to use.” The petition attracted over 100,000 signatures.

Radha Mohan points out that Bhaktivedanta Manor is ISKCON UK’s flagship temple with Deities installed by Srila Prabhupada, a high standard of worship and tens of thousands of pilgrims. It is also the UK’s foremost center for cow protection. Thus managers felt that it was important for them to stand with vegetarian, vegan and Hindu groups across the UK on a united principle.

“Ultimately it’s a good opportunity to highlight issues of animal rights, and how so many animal products are sneaked in there, not just in objects but in our food as well,” Radha Mohan says.

He also explains that because the new polymer note is so tough and practical, it’s likely to act as a pilot for other notes in the future. Therefore taking a stance now could stop all UK currency being made with meat fat in the future.

Sure enough, the Bank of England has already responded, saying it is treating the concerns with “utmost seriousness” and that its supplier is working on “potential solutions.”

Still, other ISKCON temples in the UK are continuing to accept the note for a combination of philosophical and practical reasons.

All money, they say, is contaminated. Many banknotes contain traces of cocaine. Some are even made with gelatin, another animal product, to give them extra strength. All have been used at some point in their lifetime in activities such as gambling, meat-eating and pornography. So we cannot avoid contaminated currency. Rather, when we reclaim the notes for Krishna and use them in His service, they become purified, and the people who donated them are benefitted.

Devotees choosing not to institute the ban also ask the question “How far do we go?” Do we ban all items containing animal products from the temple, including car tyres, plastic bags, paint, candles, and even computers? Do we turn away guests wearing leather shoes?

Some suggest that Srila Prabhupada would not have supported such activism. They cite the occasion when devotees in the 1970s suggested protesting against slaughterhouses, and Prabhupada turned the idea down, saying we should instead give people prasadam, tell them about the consequences and continue with our preaching.

Others open up the issue to a wider debate on cow protection, appreciating that the Manor is taking the opportunity to draw attention to such topics, but encouraging its management to take as strong a stance on commercial dairy, which supports the meat industry.

Then there are practical considerations. Many temples foresee serious problems in refusing certain notes from customers. They also worry about how long to keep the ban in a country that may soon stop caring once the media hype dies down. Even if the Bank of England does stop producing the tallow notes and stops its plan to produce more in other denominations – which is not a sure thing yet — many will continue to stay in circulation.

“I understand the principle,” says one UK temple president. “I just need to know how far we’re going to go with that principle.”

Bhaktivedanta Manor has responses to some of the arguments against the ban. Radha Mohan says that a guest wearing leather shoes is a different case because they are not offering them to the Deities, as they would money in the donation box.

He agrees that money used in Krishna’s service becomes purified, and points out that the ban is not being instituted with book distributors on the street, but specifically with direct donations at the Deities’ altar.

To the argument that the Manor should ban commercial dairy if they ban the notes, Radha Mohan states that Bhaktivedanta Manor already uses cruelty-free milk from its own farm as much as possible, but the reality is that its cows cannot provide enough for the whole congregation during festivals. Essentially, the Manor is doing its best.

To the argument that so many other things we use are made from animal products, he says that two wrongs don’t make a right, and that this was an opportunity to act on something the Manor’s influence might actually help change.

“We don’t live in an ideal world,” he says. “But we’re saying that whenever practical, whenever reasonable, we should not support cruelty to any living creature, as much as possible. It’s a case of just doing our best, and standing up for principles we feel are right, at times when we feel we can make a difference.”

More discussion could certainly continue on these points, and currently other temples not participating in the ban are opening up a bigger dialog with Bhaktivedanta Manor. Of course, all temples agree with the principle that they would rather not have to use notes with meat fat in them. And the Manor says it respects whatever decision each individual temple makes.

“This is an example of one of the kinds of issues that ISKCON and its members are going to have to grapple with today and in the future as we become a larger community, and as we interact more with the world around us,” comments ISKCON Communications Director Anuttama Das.

He adds: “These are very real issues about interacting with an imperfect world. How do we balance philosophical stances on issues with the practicalities of existing within the larger society? And at the same time, influence the world around us through a more sattvic way of life that does not abuse the environment and other living beings.”