Book Review: Christ and Krishna: Where the Jordan Meets the Ganges

By Vineet Chander (Vyenkata Bhatta Das) | Июл 13, 2012

Originally published in the Journal of Vaishnava Studies.

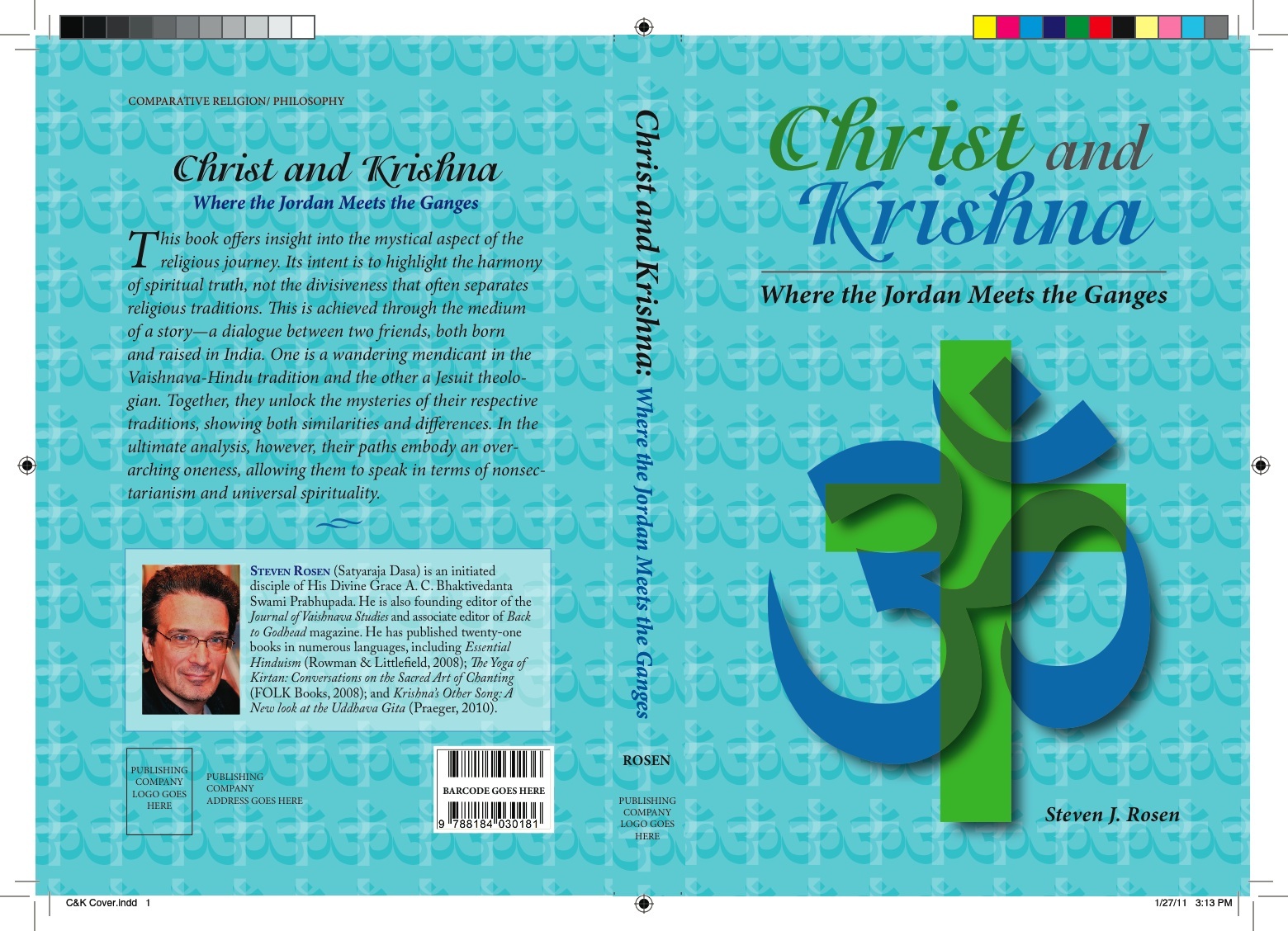

Christ and Krishna: Where the Jordan Meets the Ganges (New York, FOLK Books, 2011), 140 pp., by Steven J. Rosen

Christ and Krishna. Much has been said about these two figures. From rigorous academic comparisons of their narratives, to New Age attempts at synthesizing their teachings, to wildly speculative conspiracy theories that they were, in fact, the same historical person—the more cynical among us might conclude that nothing more can (or should) be said about this subject. Fortunately, author and scholar Steven J. Rosen is not one to let cynics get in the way of exploring what beckons to be explored. The result is Christ and Krishna: Where the Jordan Meets the Ganges (FOLK Books, 2011), a refreshing and engaging look at devotional Christianity and Vaishnava Hinduism in conversation. The book’s diminutive size (a concise and readable 140 pages) and casual tone belie its powerful impact; it is as informative as it is informed, and as moving as it is grounded in impeccable scholarship and thoughtful analysis.

Of course, this is hardly surprising to those who are familiar with Rosen’s work and qualifications. A versatile writer, he is as comfortable authoring a textbook on Hinduism (Essential Hinduism, Praeger, 2008) or editing a well-respected academic journal (The Journal of Vaishnava Studies, which he founded) as he is musing on the parallels between Star Wars and the Ramayana (The Jedi and the Lotus, Arktos Media, 2010). Moreover, Rosen gets interfaith. He served for many years as the director for interreligious affairs for the New York chapter of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. As a Jewish-born practitioner of a tradition with roots in India, Rosen also has a unique (if not complicated) lens through which to peer at both Abrahamic and Dharmic faiths.

In fact, my first encounter with Rosen’s work came when, as a High School student perusing a bookstore in my native New York City, I chanced upon a short book on interfaith dialogue he co-authored. The book, called East-West Dialogues (FOLK Books, 1989), featured transcripts of conversations between Rosen and the Rev. Alvin V.P. Hart, head chaplain at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital. As I read through the book, I became thrilled that such dialogue actually happened—and in my own backyard, as it were. Coincidentally, many years later my own vocational journey would find me serving as a chaplain at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital as well. As the only Hindu in a program that was largely dominated by and rooted in a Christian model of pastoral care, I dug up my old copy of East-West Dialogues (by now, well-read and dog-eared) to help me navigate through the experience.

If Rosen and Hart lay the foundation in East-West Dialogues, Rosen builds on that foundation in Christ and Krishna in order to explore intersections and parallels between the two faiths on a deeper level. This is laudable for a number of reasons. In the present review, I’d like to focus on three things about Christ and Krishna that particularly struck me: Rosen’s stylistic choice to present the book as a dialogue between old friends; his straightforward and courageous tackling of uncomfortable issues; and his sensitivity to religious feeling as a valid aspect of interfaith dialogue.

I feel that one of the book’s greatest strengths is the way in which Rosen frames the dialogue itself. By presenting the exploration of these two faiths as a fictional conversation between two childhood friends—Father Francis (Frank) and Saragrahi Maharaj (Swami)—whose lives have led them to embrace commitments to different faiths, Rosen immediately and naturally draws us away from the theoretical and into the realm of the personal. Employing a narrative involving characters makes for more engaging reading, of course, but it does much more. It also conveys the awareness that truly meaningful interfaith dialogue doesn’t take place on the level of religions in conversation, as much as it does on the level of people in conversation.

This awareness seems to be on the rise. Many of us have experienced, especially in the last five to ten years, a palpable shift in the way people of faith now view interfaith dialogue. Increasingly, the institutional, formal and doctrine-driven approach that dominated the field in previous decades seems to be giving way to the personal, informal, and relational model. Rosen is able to show the obvious benefits of such an approach through Frank and Swami’s interactions. As readers, we benefit from the theological insights and wisdom that Rosen writes into their dialogue, but we also get an invaluable glimpse into the context within which that dialogue takes place. We witness them eat together and walk together; we eavesdrop on them as they laugh while sharing their childhood memories; in an especially poignant scene, we find them gazing out at the vastness of the Ganges river and waxing philosophical, coming to terms with the bittersweet truth that their paths have called them in different directions. All of this is, at least according to some of us, is a critical part of what it means to “do interfaith” in the real world, and Rosen captures it beautifully.

Secondly, I feel that Christ and Krishna is admirable for its boldness in addressing, head on and unapologetically, thorny issues that often go untouched in Hindu-Christian dialogue. For instance, Rosen writes Frank as a former Hindu who converted to Christianity, and has Swami raise the issue of his conversion at the very outset of their dialogue, early in the book. How refreshing and courageous! Rosen could have easily avoided the uncomfortable conversation altogether. He could have had Swami remain silent on his friend’s choice, or could simply have written Frank as someone born into Christianity to begin with. Instead, he chooses to call out the “elephant in the room”, and offers us an important learning opportunity in the process.

Far too many of us steer clear of issues like proselytizing and conversion while engaging in interfaith dialogue, afraid of offending the other or opening a proverbial can of worms. We keep our true feelings to ourselves, privately maintain our prejudices and reservations, and timidly dance around the issue. It may be polite, but it usually rings hollow and keeps our dialogue on a superficial, even artificial level.

Rosen, on the other hand, reminds us that deep, meaningful dialogue demands that we ask the uncomfortable questions of one another. He demonstrates how this can be done in a spirit of respect and sensitivity, perhaps drawing on his own experiences as a convert (albeit one who went from West to East). Rosen is similarly evenhanded in his tackling of other, difficult issues. Through the course of the dialogue, he has Frank and Swami touch on a number of issues—idolatry, polytheism, and vegetarianism, to name but a few—that typically make Hindu-Christian dialogue particularly challenging.

A third way in which Christ and Krishna excels is in its sensitivity to the role that religious feeling and experience plays in interfaith dialogue. The two protagonists of the book are, as Rosen presents them, veritable scholars of their own traditions and religion in general. They are obviously educated and thoughtful theologians. At the same time, they are also deep feeling practitioners—as comfortable speaking from the heart-space as they are sharing their intellectual wisdom with one another. Rosen demonstrates, through these characters, that interfaith dialogue is enriched when participants can share their feelings along with their theological viewpoints or stances. Sadly, this embrace of the validity of religious feeling is all too rare in much interfaith dialogue. By writing the characters in the way he does, Rosen gently nudges us towards a more holistic and integrated view of faith and interfaith dialogue. In this respect, we might see another layer of meaning behind Rosen’s titling his book Christ and Krishna.

The book is less about comparing these two Deities, perhaps, than it is about the meeting of two practitioners who have fallen so deeply in love with Christ and Krishna respectively, that they can’t help but share their stories with one another. Swami and Frank are, one might argue, at their dialogical best when they are expressing to one another just what it is about Christ or Krishna that has turned each of their lives so wonderfully upside down.

These strengths notwithstanding, I would be remiss to not articulate one area in which I felt this book could have been stronger. I hope that the author might consider incorporating this feedback in making revisions for any subsequent re-prints of the book, or if Frank and the Swami should meet again (as I hope they will) in a sequel.

As I stated earlier, one of the strengths of the book is that Rosen depicts Frank and Swami as deep thinking, mature men of faith. Their conversation is informed by their traditions and spiritual practices, but also by their remarkable ability to recognize the Divine even outside of their own traditions. At times, however, this may be to a fault; they are so exemplary in their spiritual maturity that we sometimes lose the “humanness” of the characters. They become distant figures, and we (the flawed readers) may feel that we are so far removed from that elevated stage that we cease to connect with them. To cut against this possibility, Rosen might have included a few more scenes in which we get to glimpse Frank and Swami experiencing struggles or hitting a brick wall or two in their dialogue.

Rosen offers a few such detours, but only sparingly and cautiously; moments of tension are too quickly and politely resolved. As many of us have experienced, however, dialogue with a member of another faith (especially an old friend or family member who has undergone a radical conversion experience) can be joyous and fascinating . . . but it can also involve feelings of frustration, alienation, and painful challenges to one’s paradigm. Seeing the two characters act some of this out—even in the smallest of ways—might have helped us to see ourselves more in them. To be fair to Rosen, this may be a bit of an unrealistic expectation for a book of this size and written for this purpose. To flesh out Frank and Swami as fuller, more sympathetic characters would require Rosen to write the book more as a novel than a fable.

A final point: as I read Christ and Krishna, I couldn’t help but remember another book I had read a few years ago that bears some superficial similarity to this one. Ravi Zacharias’s New Birth or Rebirth: Jesus Talks With Krishna (Multnomah Books, 2008) is also a concise, lively, and readable exploration of Hinduism and Christianity. Like Rosen, Zacharias also employs the device of parable or imagined conversation (though in his case, the conversation is between the two divine personalities themselves, rather than their devotees) to convey theological and philosophical points. However that may be all that these two books truly have in common.

While Rosen’s predilections and leanings are clear from his work, he does not play favorites in the same way that Zacharias does. He allows his readers to think for themselves. Whereas Rosen uses the medium to try to give each tradition a personal voice and convey a sense of balance and mutual respect, Zacharias does quite the opposite—taking the opportunity to expose the spurious teachings of Krishna (or, more accurately, his straw-man caricature of Krishna) as inferior to the salvation offered exclusively by Jesus. A thorough critique of New Birth or Rebirth requires it’s own review, but suffice it to say that as a Hindu chaplain, Vaishnava practitioner, and frequent participant in interfaith dialogue, I find that book morally troubling, academically dishonest, and deeply offensive. It may be presented as “comparative religion” or cloaked in pseudo-intellectual language to soften the blows, but at its core Zacharias’s book betrays a triumphalism, bigoted agenda.

I bring this up, only because it helps me to recognize that Steven Rosen’s book is fueled by an agenda of its own. Thankfully, however, Rosen’s agenda seems to be one of furthering understanding and inspiring meaningful dialogue. This he accomplishes by shining light on commonality while acknowledging—and even celebrating—that which each tradition holds as unique. And this is, perhaps, the highest compliment I can pay to Christ and Krishna. To put it bluntly: if books like the one by Zacharias spew the poison of sectarianism and prejudice, Rosen’s book provides the most effective and fitting antidote to that poison. This alone should make Christ and Krishna: Where the Jordan Meets the Ganges required reading for anyone serious about interfaith today.

Book ordering info: Only US$15.00 in the US or US$20 in Canada and Overseas. Checks or money orders payable to “FOLK Books” and sent to FOLK Books, P.O. Box 108, Nyack, NY 10960 USA