Christmas Mythology?

By | Дек 23, 2007

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, dismissed the Christmas story of the Three Wise Men yesterday as nothing but “legend.”

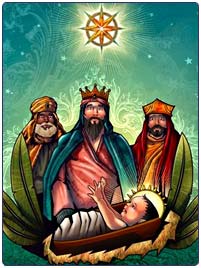

There was scant evidence for the Magi, and none at all that there were three of them, or that they were kings, he said. All the evidence that existed was in Matthew’s Gospel. The Archbishop said: “Matthew’s Gospel doesn’t tell us there were three of them, doesn’t tell us they were kings, doesn’t tell us where they came from. It says they are astrologers, wise men, priests from somewhere outside the Roman Empire, that’s all we’re really told.” Anything else was legend. “It works quite well as legend,” the Archbishop said.

Further, there was no evidence that there were any oxen or asses in the stable. The chances of any snow falling around the stable in Bethlehem were “very unlikely”. And as for the star rising and then standing still: the Archbishop pointed out that stars just don’t behave like that.

Although he believed in it himself, he advised that new Christians need not fear that they had to leap over the “hurdle” of belief in the Virgin Birth before they could be “signed up”. For good measure, he added, Jesus was probably not born in December at all. “Christmas was when it was because it fitted well with the winter festival.”

He said the Christmas cards that show the Virgin Mary cradling baby Jesus, with the shepherds on one side and the Three Wise Men on the other, were guilty of “conflation”.

But in spite of his scepticism about aspects of the Christmas story, as told in infant nativity plays up and down the land, he denied that believing in God was equivalent to believing in Santa Claus or the tooth fairy.

“The thing is, belief in Santa does not generate a moral code, it does not generate art, it does not generate imagination. Belief in God is a bit bigger than that,” the Archbishop said.

Dr Williams was speaking live on BBC Radio Five to the presenter Simon Mayo when Ricky Gervais, star of The Office and a fellow guest, challenged him about the intellectual credibility of the Christian faith.

He said he was committed to belief in the Virgin Birth “as part of what I have inherited”. But belief in the Virgin Birth should not be a “hurdle” over which new Christians had to jump before they were accepted.

He hinted that decades ago he was not “too fussed” with the literal truth of the doctrine of the Virgin Birth. But as time went on, he developed a “deeper sense” of what the Virgin Birth was all about. And he went on to do a literary-critical analysis of the traditional Christmas card that features, as often as not, a Virgin Mary cradling a baby Jesus wrapped in swaddling clothes, with shepherds on one side, the Three Wise Men on the other and oxen and asses all around. Sometimes the stable is depicted with snow falling all around, and often with a bright star rising in the East.

Most of it, the Archbishop said, could not have happened like that.

One of the few things that almost everyone agreed on was that Jesus’s mother’s name was Mary. That is in all the four Gospels. It was also pretty clear that Jesus’s father was called Joseph.

Dr Williams was not saying anything that is not taught as a matter of course in even the most conservative theological colleges. His supporters would argue that it is a sign of a true man of faith that he can hold on to an orthodox faith while permitting honest intellectual scrutiny of fundamental biblical texts.

The Archbishop admitted that the Church’s present difficulties, with the dispute over sexuality taking the Anglican Communion to the brink of schism, were off-putting to outsiders. “They don’t want to know about the inside politics of the Church, they want to know if God’s real, if they can be forgiven, what sort of lifestyles matter more and they want to know, I suppose, if their prayers are heard.”

Dr Williams’s views are strictly in line with orthodox Christian teaching. The Archbishop is sticking to what the Bible actually says.

The essential part of the Christmas story is the baby. God came to us in human form, as part of creation and absolutely integral to it. That is the heart and essence of it. This is why the last reading at the service of Nine Lessons and Carols held in churches throughout Britain at this time of year is the first few verses of John’s Gospel, about the incarnation of the “Word”. This culminates in that spine-chillingly wonderful declaration: “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth.” Without that, Christmas would be a rather vague festival.

In carols we sing about a baby, sweet and mild, one that “no crying makes”. This is wishful thinking, along with other parts of the story.

But some of it cannot be challenged, such as Mary, or in Greek, “Theotokos”, literally “God-bearer”. Her willingness to be part of God’s plan is central.

There seems little doubt that Jesus was born in a stable. The Bible says “outside the house”, and this was probably because the house was full. If it was a stable, there could have been animals at the birth of Jesus. We are also told that there were witnesses from the fields, shepherds taken by surprise by the news from the angels, rushing down from the hillsides, wondering in awe and then going back to their sheep, transformed by the coming of the baby.

The Wise Men were witnesses of the opposite kind. They were careful, calculating, educated men who think that they begin to discern God’s imminent arrival and who blunder their way across the region until they find what they think they’ve been seeking. They, too, go back transformed.

These are the really important bits of the story.