From Tons of Manure, a Growth Industry

By Gerri Hirshey | Мар 07, 2009

IN almost-spring, as itchy gardeners drag out grow lights and seed-starting flats, it seems a fitting moment to trace the germ of a new and very green gardening idea. It first took root beside a reeking, unspeakable lagoon in the northwest corner of Connecticut and is blossoming sweetly nationwide. Kindly summon a gardener’s tolerance for earthy subject matter as this gritty tale unfolds:

More than a decade ago — she thinks it was in 1998 — Jane Slupecki, a marketing representative for the Connecticut Department of Agriculture, took a group of Litchfield County dairy farmers to a brainstorming dinner at a lovely lakeside inn there. Her agency had a small grant to try to find possible solutions to a big, stinky problem.

“Cow manure,” Ms. Slupecki recalls. “Endless tons of it. We were concerned about how farmers returned manure nutrients to their fields, and how we could prevent runoff of excess nitrogen and phosphorus into watersheds.” Since farms in riparian areas were of particular concern, most of the dairymen invited to dinner were grazing cows near the Blackberry River, which in turn feeds the mighty Housatonic. Their hostess remembers it as “just a lovely dinner,” but we will spare the reader the technical points of the conversation.

“Cow poop is cow poop,” admits Ms. Slupecki, who was feeling some frustration at the paucity of workable suggestions by the time they reached dessert and coffee. Half in jest, she blurted, “Can’t you guys do something with this stuff — make a flowerpot or something?”

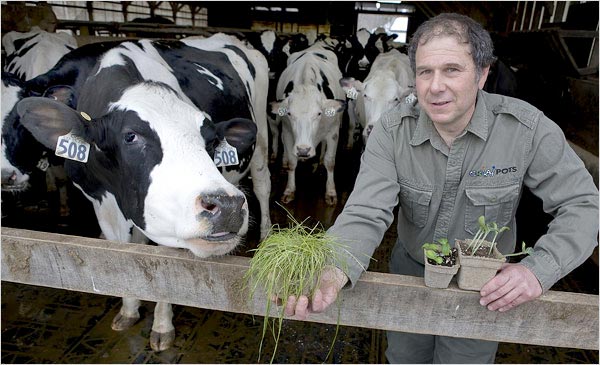

Those were fateful words for brothers Ben and Matthew Freund, second-generation dairy farmers who at the time maintained a herd of 225 Holsteins in East Canaan. Each cow produces 120 pounds of manure daily. Why not grow flowers and tomatoes from cow flops? It took eight years’ development, a $72,000 federal grant secured through Connecticut’s Agricultural Businesses Cluster, and countless grim experiments. Now their manure-based CowPots — biodegradable seed-starting containers — are being made on the farm and sold to commercial and backyard growers who prefer their advantages over plastic pots.

Molded of dried, deodorized manure fibers, CowPots hold water well, last for months in a greenhouse and can then be planted directly into the ground, sparing the seedling transplant shock and letting tender new roots penetrate easily. As the pots decompose, they continue to fertilize the plant and attract beneficial worms.

According to Matthew Freund, CowPots are the natural evolution of the family’s farming philosophy. Their father, Eugene, who died in late 2008, was a graduate of Cornell University’s veterinary school and had been committed to sound environmental practices since beginning dairy farming in 1949. At the time of Ms. Slupecki’s dinner, the Freunds already had a methane digester to process manure, built in part with a government grant. Beginning in 1997, theirs has been one of the rare farms in the United States continually extracting methane gas from cow manure in a digester. The methane can power a generator to save electricity costs, and the digester also removes the most pungent odors.

“With a small herd like we have now, 250 cows, there’s not a lot of monetary payback from it,” Mr. Freund says. “But it heats our house, gives us hot water and lets us heat the manure, making it easier to pump.” While the digester does not reduce the nutrient load, it makes the waste easier to manage in accordance with requirements of the 1972 Clean Water Act. Shipping off the solids as CowPots certainly helps. “We’re in compliance,” Mr. Freund says. “But a lot of guys are in trouble.”

The cows’ byproduct is bulldozed daily, transported and forced through a chamber with an auger that separates solids and liquids. “The digester tank is 100 degrees, the same temperature as a cow’s stomach,” Mr. Freund says.

The liquid fertilizer is stored in an 800,000 gallon holding pond for use on the fields. Taking Ms. Slupecki’s suggestion to heart, Mr. Freund addressed the mountains of fibrous, grainy-smelling solids. His early experiments — shaping pots of dried manure and Elmer’s Glue, then baking them in his wife Theresa’s toaster oven — were hardly marriage-enhancing. “O.K., she couldn’t use the oven anymore. But she was all for it. She’s a farm girl herself. We’re conservative and cheap, and make do with what we have.”

The first marketable CowPots were produced by hand in December 2007 for the 2008 growing season. Now the process is mechanized, the patent is pending and the Freunds have offloaded what Mr. Freund calls “the really hard jobs” — marketing and distribution — to the Liquid Fence Company, makers of all-natural animal and insect repellents.

The Freunds have green dreams far beyond CowPots, though most are too proprietary to divulge. Just one? “Think about golf tees made of composted manure that fertilize greens when discarded.” With other local dairymen, they are looking into the feasibility of a cooperative venture to combine the methane gas produced by 2,500 cows on three farms to contribute to the power grid. “By our calculations, we could deliver three megawatts and light the town of Canaan,” Mr. Freund says. “It would be a lot of fun.”

He only hopes that he and his neighboring farmers can last in their primary business. Nationwide, dairy farmers are struggling as never before. As exports have plunged and financially ailing Americans buy less milk, prices set by the commodities market have been in free fall. Already, herds are being auctioned off throughout the country.

Last June, milk was selling for nearly $20 a hundredweight. Mr. Freund expects that to drop to $12 by next year — far less than farmers’ expenses to bring milk to market. He says that the Agriculture Department’s cost-of-production calculations average $26 per hundredweight in New England states. Though he is pleased with the modest success of his value-added product, he muses, “It’s a strange world when poop is more valuable than milk.”