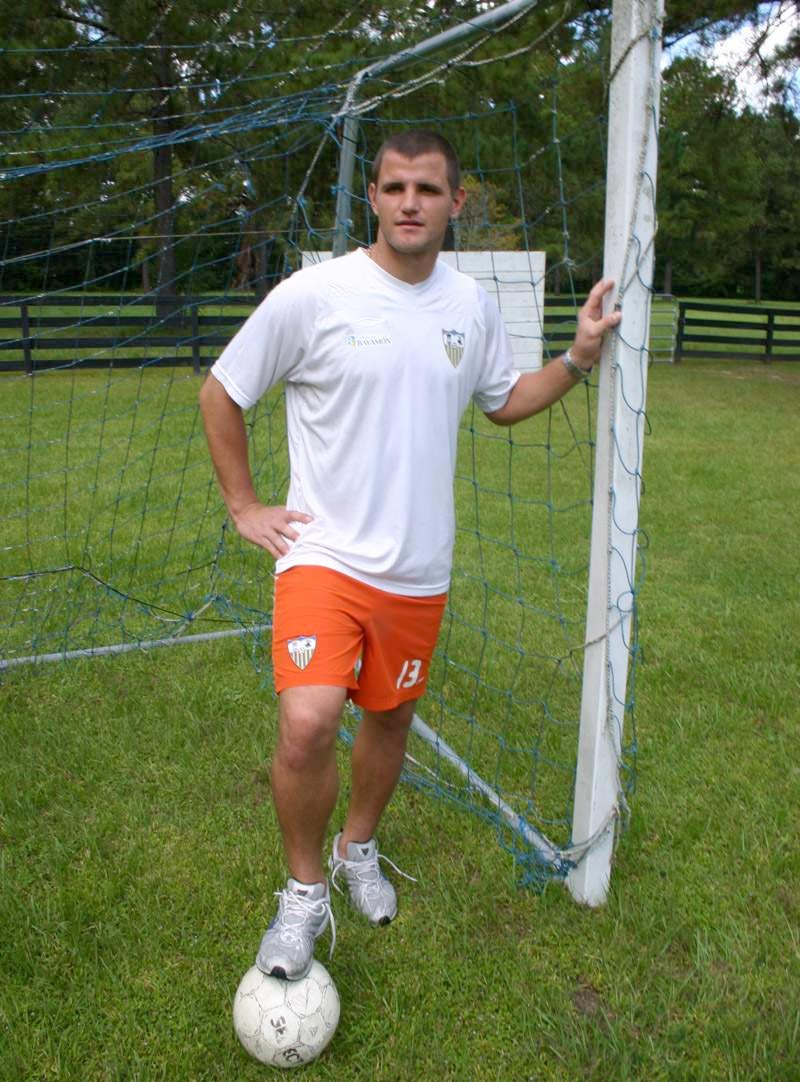

Hare Krishna Athlete Learning to Play at Top Club Level

By Nathan Deen | Окт 18, 2009

ALACHUA — Devala Gorrick wouldn’t take no for an answer.

He didn’t compromise when his college of choice denied him admission, and he wasn’t going to let any coach tell him he had a problem with his shoulder.

Gorrick, an Alachua native whose family is part of the area’s Hare Krishna community, pinched a nerve in his right shoulder while trying out for Puerto Rico’s Bayamon Futbol Club. He missed two days of practice. When he came back, he had a good workout and expected to be signed.

“I was the last one to go in (the coach’s office) and everyone before me had walked out with signed contracts,” Gorrick said. “I went in there and they said go home.”

They were afraid his shoulder was worse than it was. All Gorrick asked for was the chance to convince them otherwise.

Gorrick stayed on and earned the starting goalie position. Lucky for Bayamon coach Jack Stefanowski, considering Gorrick helped lead Bayamon to the Puerto Rico Soccer League Championship on Sept. 5, defeating San Juan Athletic 1-0. Gorrick played for Bayamon from May through September and will return to the team in January to prepare for the Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF) tournament in February. The prestigious tournament features professional clubs from the United States, Canada and the Caribbean.

“We were hesitant early on,” Stefanowski said, “but once he came in and proved himself, we decided to sign him. I thought he did a fantastic job coming in and getting us to the championship game.”

Though homeschooled until the time he entered college, Gorrick played soccer for Santa Fe High School and helped the team win its only district title.

With the help of a mentor, Mark Dillon, Gorrick got the opportunity to raise his game to another level. At 15, he began playing for Ajax Orlando, coached by Dillon, an affiliate team of Ajax Amsterdam, a popular European soccer club.

“That was a whole different level that I wasn’t ready for,” Gorrick said. “It was a very high training level. He expected us to be in shape. He didn’t accept anything less. That’s gotten me into the mindset of being the best.”

Dillon’s program became known for its disciplinary and advanced training techniques, which focus on speed and explosiveness. Gorrick remembers the exhaustion of ‘parachute’ drills, in which a bungee cable or a parachute is attached to a player’s waste to make players fight off resistance.

Dillon was also the one who helped Gorrick straighten his life out as a teenager. Gorrick didn’t listen to his parents, he ran away from home, stayed out late and got into trouble at school. When all else failed, his parents, Dennis and Diane, called Dillon.

“Anytime we have an opportunity to provide guidance on or off the field is always a great opportunity for us,” Dillon said. “He responded to discipline and I think our program is a lot more disciplined than other programs.”

After Gorrick helped Ajax win the Disney Wide World of Sports Cup, Dillon sent Gorrick to play in Europe for Austrian and Germany youth teams.

“He did me a lot of favors,” Gorrick said. “He’s practically an agent over there.”

Next, Dillon suggested college.

At 19 years old, Gorrick was going to go to Barry University in Miami to play soccer. No one could tell him otherwise. Not even the Barry University admissions office.

“My grades aren’t good enough?” he thought. Fine. He had one more semester left at Tyler Junior College (Texas) and by his calculations, if he made all A’s that semester, he would get the 3.3 GPA he needed.

When he received his final grades, an “A” lay next to every class listed. But there was a problem — Barry still said no. He had miscalculated. His average turned out to be 3.29, a hundredth of a point short of the Barry requirement. And an exception wouldn’t be made. It was 3.3 or nothing.

A little more participation could have made the difference. There may have been many things he could have changed in those two years to get the 3.3, but the few lectures he missed in English stood out to him. He had made a C in that class. What could he do now? Hard work and determination had always rewarded him until then.

He sent e-mails and wrote letters to every professor he had, explaining his problem. That very same English teach replied and told Gorrick that if he wanted his grade changed, he would have to work for it. Less than two months before the 2007 fall semester would begin at Barry, he would have to complete a 20-page paper to get his grade changed. He would do whatever it took.

“It took two weeks to actually change the grade and I finally got the letter saying I had a 3.31,” Gorrick said. “I was at Barry the next week. Those few classes I missed almost changed my whole college history.”

This winter, Gorrick will partake in two of the biggest stages of his life: graduation in December and CONCACAF in February.

“I don’t know what to expect, to be honest,” he said. “I don’t know what we’ll do. I don’t know if our team will be prepared. We’re definitely going to have to bring our level up. This is a league or two above us.”