ISKCON 50 Meditations: November 29, 2016

By Satsvarupa dasa Goswami | Ноя 29, 2016

Swamiji and “The Hare Krishna Chanters” Produce a Record Album

Alan Kallman was a record producer. He had read the article in The East Village Other about the swami from India and the mantra he had brought with him. When he had read the Hare Krishna mantra on the front page, he had become attracted. The article gave the idea that one could get a tremendous high or ecstasy from chanting. The Swami’s Second Avenue address was given in the article, so one night in November, Alan and his wife visited the storefront.

As soon as Alan mentioned his idea about making a record, Prabhupada was interested. “Yes,” he said, “we must record. If it will help us distribute the chanting of Hare Krishna, then it is our duty.” They scheduled the recording for two weeks later, in December, at the Adelphi Recording Studio near Times Square. Alan’s wife was impressed by how enthusiastically the Swami had gotten to the point of making the record: “He had so much energy and ambition in his plans.”

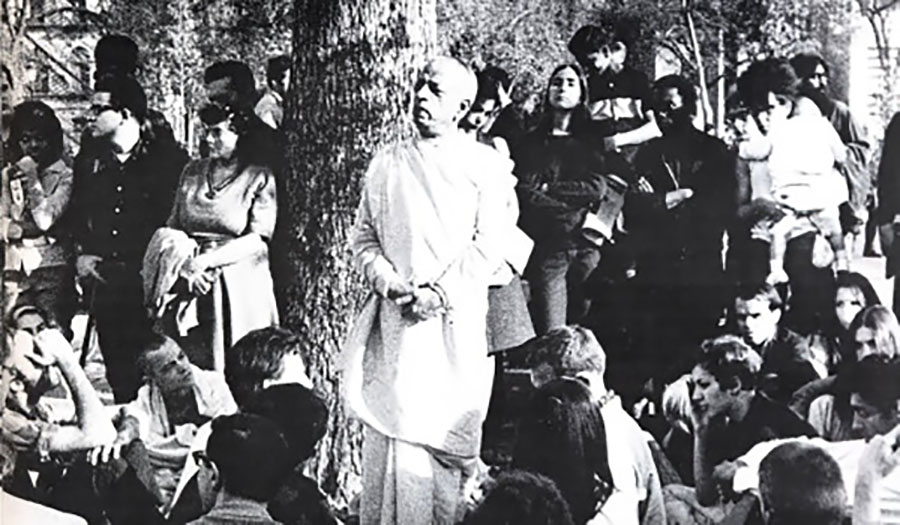

At the studio, everyone accepted the devotees as a regular music group. One of the rock musicians asked them what the name of their group was and Hayagriva laughed and replied, “The Hare Krishna Chanters.” Of course most of the devotees weren’t actually musicians, and yet the instruments they brought with them—a tambour, a large harmonium (loaned by Allen Ginsberg), and rhythm instruments—were ones they had played during kirtanas for months. So, as they entered the studio, they felt confident that they could produce their own sound. They just followed their Swami. He knew how to play and they knew how to follow him. They weren’t just another music group. It was music, but it was also chanting, meditation, worship.

The first sound was the tambour, with its plucked, reverberating twang. An instant later Swamiji began beating the drum and singing, vande ’ham sri-guroh . . .Then the whole ensemble put out to sea—the tambour, the harmonium, the clackers, the cymbals, Rupanuga’s bells, Swamiji’s solo singing—pushing off from their moorings, out into a fair-weather sea of chanting . . . lalita-sri-visakhanvitams ca . . .

Swamiji’s voice in the studio was very sweet. His boys were feeling love, not just making a record. There was a feeling of success and union, a crowning evening to all their months together.

. . . Sri-krsna-caitanya, prabhu-nityananda . . .

After a few minutes of singing prayers alone, Swamiji paused briefly while the instruments continued pulsing, and then began the mantra: Hare Krishna Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare. It was pure Bhaktivedanta Swami—expert, just like his cooking in the kitchen, like his lectures. The engineers liked what they heard—it would be a good take if nothing went wrong. The instruments were all right, the drum, the singing. The harmony was rough. But this was a special record—a happening. The Hare Krishna Chanters were doing their thing, and they were doing it all right. Alan Kallman was excited. Here was an authentic sound. Maybe it would sell.

After a few rounds of the mantra, the devotees began to feel relaxed, as though they were back in the temple, and they were able to forget about making mistakes on the record. They just chanted, and the beat steadied into a slightly faster pace. The word Hare would come sometimes with a little shout in it, but there were no emotional theatrics in the chorus, just the straight response to the Swami’s melody. Ten minutes went by. The chanting went faster, louder and faster—Swamiji doing more fancy things on the drum, until suddenly . . . everything stopped, with the droning note of the harmonium lingering.

Alan came out of the studio: “It was great, Swami. Great. Would you like to just go right ahead and read the address now? Or are you too tired?” With polite concern, pale, befreckled Alan Kallman peered through his thick glasses at the Swami. Swamiji appeared tired, but he replied, “No, I am not tired.” Then the devotees sat back in the studio to watch and listen as Prabhupada read his prepared statement.