Lord Caitanya and the Renaissance of Devotion (Part 1)

By Ravindra Svarupa Dasa | Мар 28, 2009

This article was originally published in Back to Godhead magazine in 1984.

Europe in the fifteenth century was undergoing that awesome social and cultural transformation that the historian Jules Michelet, looking back in reverence, named the Renaissance, the “rebirth.” That long medieval period, with its vision so entranced by splendid images of the eternal that it could hardly spare a glance for this fleeting world, with its mind so obsessed by last things—Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell—that it endured this life only as a hard trial and preparation, with its social body constructed of rigid hierarchies and maintained by a plodding economy—all that was finished. Like a man awakening from sleep and shaking fuzzy images of dreams from his head, Europe came alive to the senses and beheld as if for the first time the whole vast world that lay so enchantingly before it, rich with mysterious promise, beckoning with limitless possibilities.

Pico della Mirandola composed an Oration on the Dignity of Man. Still depicting pious subjects, Michelangelo carved in rock the grace and strength of a perfectly proportioned, smoothly muscled David and shaped a hymn in glorification of the male body, while everywhere painters adorned walls with the supple limbs and lustrous complexions of ripely rounded, exquisitely charming Madonnas. Bold navigators turned their prows into uncharted seas and found new worlds for exploration and exploitation. In the grip of a relentless fascination, Leonardo da Vinci limned in notebooks painstaking studies that delved into the intricacies of human anatomy and the mechanics of birds in flight. Based on a new, manmade kind of wealth, a new, self-made aristocracy arose—”merchant princes” who created far-flung empires of trade, banking, and manufacture. And so it happened that in a great shift of human vision from God to man and matter, the modern world was born.

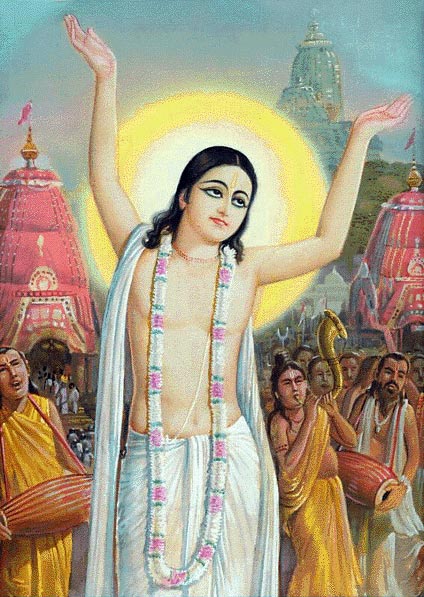

India in the fifteenth century was also undergoing a renaissance—of a quite different sort. It was indeed almost the opposite of the European one; scholars have called it the “бхакти renaissance,” a great rebirth of devotion to God. The preeminent figure of this powerful religious upsurge was ÅšrÄ« Caitanya MahÄprabhu.

When modern researchers explain historical changes, they, of course, consider only mundane causes—social, political, economic, and other such factors. However, I want to explore here another kind of cause: the divine. The Bhagavad-gÄ«tÄ explains briefly how and why God periodically intervenes in human history: “Whenever and wherever there is a decline in religious practice,” Kṛṣṇa declares, “and a predominant rise of irreligion—at that time I manifest Myself. To deliver the pious and to annihilate the miscreants, as well as to reestablish the principles of religion, I Myself appear, millennium after millennium.”

As an introductory text, the Bhagavad-gÄ«tÄ succinctly presents general principles. More advanced texts, like the ÅšrÄ«mad BhÄgavatam, furnish further information. Drawing on such works, ÅšrÄ«la PrabhupÄda comments on the statement of the Bhagavad-gÄ«tÄ: “It is not a fact that the Lord appears only on Indian soil. He can manifest Himself anywhere and everywhere, and whenever He desires to appear. In each and every incarnation, He speaks as much about religion as can be understood by the particular people under their particular circumstances. But the mission is the same—to lead people to God consciousness and obedience to the principles of religion. Sometimes He descends personally, and sometimes He sends His bona-fide representative in the form of His son, or servant, or Himself in some disguised form.”

Why should God have to appear over and over again? After all, if God is perfect, shouldn’t He be able to establish religion perfectly? Shouldn’t once suffice for all? It is, however, the nature of the material world that all things decay in time, and while God is infallible, the human beings who receive and transmit God’s instructions are fallible. Consequently, the religious traditions God establishes become compromised and undermined by a worldly spirit, and so in time they disintegrate. When religion thus declines, and irreligion consequently rises, God descends to rectify the imbalance and restore the principles of righteousness. God’s periodic intervention is crucial. Kṛṣṇa notes in the Bhagavad-gÄ«tÄ that if He did not act in this way, “all these worlds would be put to ruination.”

The Renaissance in Europe offers a clear instance of the decline of religion. Fifteen hundred years earlier, Jesus Christ, the son of God, had appeared in a remote corner of the Roman Empire and had taught, as far as possible, the principles of religion. His followers, adopting and transforming the philosophical heritage of the Greeks and the practical and material legacy of the Romans, had eventually created in Europe a God-centered civilization. But the Renaissance, as a great movement of secularization, signaled the destruction of that civilization. Priestly worldliness and corruption had vitiated the spiritual power of the Church (as anyone familiar with the history of the Renaissance popes can attest). Although Martin Luther and other reformers attempted to restore the purity of Christianity, they unintentionally provided the means for European rulers to break loose from religious control. Thus the Reformation greatly contributed to the dismantling of the medieval God-centered civilization.

If Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries illustrates the sort of religious decline described in the Bhagavad-gÄ«tÄ, India in the same period illustrates the divine restoration. The transcendental agent in this case was ÅšrÄ« Caitanya, who appeared in what is now West Bengal in 1486, just four years after Luther’s birth in Germany.

A person should be accepted as an incarnation of God only if He is referred to in scriptures. Many scriptures foretell the advent of Lord Caitanya. The ÅšrÄ«mad-BhÄgavatam (11.5.32) says: “In the age of Kali, intelligent persons perform congregational chanting to worship the incarnation of Godhead who constantly sings the name of Kṛṣṇa. Although His complexion is not blackish, He is Kṛṣṇa Himself. He is accompanied by His associates, His servants, His weapons, and His confidential companions.”

This verse identifies Lord Caitanya as a special kind of incarnation called a “yuga-avatÄra.” Vedic literature describes history as cyclical, progressing through repeated revolutions of four great ages called yugas. The first age of the cycle, Satya-yuga, is a golden age of immense spiritual and material well-being; each subsequent age ushers in a decline. We are now five thousand years into Kali-yuga, the final and most debased age. “In this iron age of Kali,” the BhÄgavatam says, “men have but short lives. They are quarrelsome, lazy, misguided, unlucky, and, above all, always disturbed.”

Religious practice has to be tailored to fit the particular characteristics of each of the yugas. The meditational practices suitable for Satya-yuga, for example, will be ineffective in the Kali-yuga. People no longer have the time, the determination, and the peace of mind to meditate properly. The Lord therefore descends in each yuga—as the yuga–avatÄra—in order to establish the appropriate form of religion. According to the ÅšrÄ«mad-BhÄgavatam, Lord Caitanya is the yuga–avatÄra for this age of Kali.

The BhÄgavatam also notes the specific religious practice Lord Caitanya will propagate: saá¹…kÄ«rtana, the congregational chanting of the name of God. Saá¹…kÄ«rtana is especially suitable for Kali-yuga, because it is both easy to do and extremely powerful. In this age we are in such a morbid condition of soul that only the strongest of remedies can heal us. And we will refuse the medicine unless it is sweet and easy to take. Therefore, Lord Caitanya disseminated the holy name. No matter how quarrelsome, lazy, misguided, unlucky, and disturbed we may be, we can easily chant Hare Kṛṣṇa with perceptible spiritual results. We will at once have a taste of transcendental bliss and feel lust, greed, and anger diminish. The immeasurable potency of the divine name will rid even the most polluted mind of the putrefaction of material existence.

Lord Caitanya possessed such immense spiritual power that waves of devotion spread out from Him and inundated all of India with love of God. His life and teachings have been expertly recounted by KṛṣṇadÄsa KavirÄja GosvÄmÄ« in ÅšrÄ« Caitanya-caritÄmá¹›ta, universally recognized as a classic of Bengali literature. We can get some idea of Lord Caitanya’s potency from this description of the Lord’s impact on people during His tour of South India:

Whenever Lord Caitanya met anyone, KṛṣṇadÄsa KavirÄja says, He would ask them to chant Hare Kṛṣṇa. “Whoever heard Lord Caitanya MahÄprabhu chant ‘Hari, Hari,’ also chanted the holy name of Lord Hari and Kṛṣṇa. In this way, they all followed the Lord, very eager to see Him. After some time, the Lord would embrace these people and bid them to return home, after investing them with spiritual potency. Being thus empowered, they would return to their own villages, always chanting the holy name of Kṛṣṇa and sometimes laughing, crying, and dancing. These empowered people used to request everyone and anyone—whomever they saw—to chant the holy name of Kṛṣṇa. In this way all the villagers would also become devotees of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. And simply by seeing such empowered individuals, people from different villages would become like them by the mercy of their glance. When these individuals returned to their villages, they also converted others into devotees. When others came to see them, they were also converted. In this way, as those men went from one village to another, all the people of South India became devotees. Thus many hundreds of people became Vaiṣṇavas [devotees of Kṛṣṇa] when they passed the Lord on the way and were embraced by Him” (Cc. Madhya 7.98-105).

A unique feature of Kṛṣṇa’s appearing as Lord Caitanya is that although Lord Caitanya is Kṛṣṇa Himself, He does not appear as God but rather as a devotee of God. There are two reasons why God assumes the role of His own devotee, one of them external and public, the other internal and private.

The public reason God comes as a devotee is to teach the chanting of the names of God in the most attractive and powerful way. By playing the part of His own devotee—the greatest devotee of all—Kṛṣṇa is able to show by His own peerless example the splendor of pure devotional service. Since Lord Caitanya is God Himself revealing to us how He wishes to be served, the teachings of Lord Caitanya are most authorized.

God’s private reason for descending as Lord Caitanya is more difficult to grasp, and to understand it we will have to enter into some of God’s confidential, internal affairs.

(to be continued)