The Life of Devotional Dynamism

By Chaitanya Charan Das | Янв 19, 2017

“What we are is God’s gift to us; what we become is our gift to God” – Eleanor Powell

I first came across this quote many years ago and found it intuitively, inspiringly insightful. Over the years, I have contemplated it in the light of the Bhagavad-gita’s bhakti wisdom, wisdom that was probably unknown to Powell.

What we are

In our life-journey, we all are at different points based on our starting point at birth and our present status. At birth were determined our genes, our congenital endowments and our families. Presently, we all are characterized by various designations such as age groups, educational levels, economic brackets, religions and nationalities. We often identify with these things, thinking that their combination is what we are. But we are much more.

The Bhagavad-gita explains that we are souls, spiritual beings distinct from our bodies. We stay in one body for one lifetime and then move on to another body (02.13), just as people give up worn-out clothes and put on new ones (02.23).

While in a particular body, we have our distinctive blend of strengths and weaknesses. But these don’t define us so much when we appreciate that our core is spiritual. We understand that these weaknesses stem from the material part of us that is not actually us. The body is an essential interface for the non-material soul to function in this material world. Still, it is an impure instrument that can sully the pure soul’s actions.

Of course, we can’t blame the body for our limitations because it is a fruit of our own past karma. Nonetheless, we are not our karma – we are spiritual beings distinct from our past actions and their consequences, even consequences that manifest consequentially as our material vehicles.

By knowing ourselves as essentially spiritual, we can avoid lamenting about our deficiencies and focus on our abilities. Thus discovering and developing our talents, we can become the best that we can be. We need to be aware of our limitations, but that awareness needn’t be at the center of our consciousness. Unfortunately, thoughts of our limitations often dominate our consciousness when we see ourselves materialistically, because materialism holds that matter is all that exists. In contrast, bhakti wisdom helps us place our material side at the periphery of our identity and focus on our spiritual potential, thereby freeing us to bring out our best.

God’s gift to us

Our very existence expresses God’s love for us: we are meant for a life of eternal love with him. Bhakti wisdom reveals God to be not just supreme, but also supremely lovable – he is the all-attractive Supreme Person, Krishna.

Eternal love for Krishna is best reciprocated in the spiritual realm, in his personal abode. And our life in this world can prepare us for that life of love. Thus, our existence, with our innate longing to love and be loved, and with the opportunity to fulfill that longing perennially – all this is God’s gift to us.

Moreover, what we presently are is not just the random result of our karma. The Bhagavad-gita (09.10, 13.23) states that material nature works under Krishna’s supervision. He orchestrates material things in a way that is best for our learning and growth. When seen from the perspective of the past, what we are is a result of our karma. But when seen from the perspective of the future, what we are is a divine gift, a customized takeoff point for our spiritual evolution. Expressing a similar positive view of our abilities, the Gita (07.08) states that human abilities are manifestations of the divine in this world.

This devotional vision can help us counter one of our biggest enthusiasm-eroders: unhealthy comparison. When we see those more talented than us, we may feel sorry for ourselves. Such self-pity can dishearten us and sentence us to a lifelong struggle for becoming like them. But they are who they are, and we can never become them; we can only become second-class imitations of them.

Bhakti wisdom protects us from such unworthy labor by giving a healthy boost to our self-esteem. If God had wanted us to be someone else, he would have made someone else. But he chose to make us, us – that means he wants us to be us. Of course, he wants us to be the best us, not the worst us, which is what we may become if we act imprudently.

For helping us bring out our best, the Bhagavad-gita recommends a social division of labor that engages people according to their natural endowments (04.13). While this system has, over the centuries, degenerated into the discriminatory caste system, its original purpose was inclusive. The Gita (18.45) assures that we all can, by working according to our own nature, attain perfection. This implies that whatever we are is suitable for our growth.

Given that we all are differently endowed, comparison is unavoidable – all the more because we live in a competitive world. But we can avoid unhealthy comparison. How? By taking inspiration from others’ talents and using that inspiration to tap our talents and enhance our contributions in a mood of devotion.

Of course, we can take inspiration from exemplars, especially exemplars on the spiritual path, and follow in their footsteps with whatever capacities we have.

The healthiest comparison is comparison with oneself. If we can strive, on a daily basis, to become a better version of what we were the previous day, we will be on the sure path to growth.

What we become

We all have an innate drive to change ourselves for the better and to change things around us for the better. This is a characteristically human drive. Birds live in the samenests and eat the same foods, year after year, generation after generation. They change only when forced to adapt by environmental changes. We humans, however, have the drive to improve things, as seen from our hundreds of architectural styles and cuisines. Indeed, all art, literature and science stems from this human drive to make things better.

Some people fear that this human drive will be choked in a life of devotion. However, devotion doesn’t stifle our initiative, but sublimates it.

Bhakti wisdom urges us to direct our drive to improve upwards in the realm of consciousness, for actualizing our spiritual potential and sharing it with others. Significantly, bhakti doesn’t divorce the material from the spiritual; it harmonizes the material with the pursuit of the spiritual. Some spiritual paths reject the material as profane. In positive contrast, bhakti acknowledges that even the material emanates from the supreme spiritual reality, as the Gita (10.08) indicates when stating that everything comes from Krishna.

Undoubtedly, bhakti focuses on direct devotional activities such as chanting, studying scripture and worshiping the deities. These activities purify our consciousness and infuse it with an attitude of devotional service towards Krishna. Additionally, bhakti urges us to carry this service attitudeto the whole of our life and to redefine our work as a form of worship.

The Gita (18.46) states that God is the source of everything and that he pervades everything – being thus immanent, he can be worshiped through our vocations. Being thus energized by a mood of service and contribution, we get a purpose for our hard work that is both lofty and steady.

Within a materialistic worldview, we work hard for gaining recognition in the world’s eyes. But the world usually recognizes only the top performers. If we don’t become one, we remain unrecognized and feel unworthy. Further, today’s money-centered culture often makes us reduce, consciously or subconsciously, our self-worth to our net worth. Such equalization, which can wreck our self-confidence, can be prevented by internalizing the lofty vision of contribution provided by bhakti wisdom.

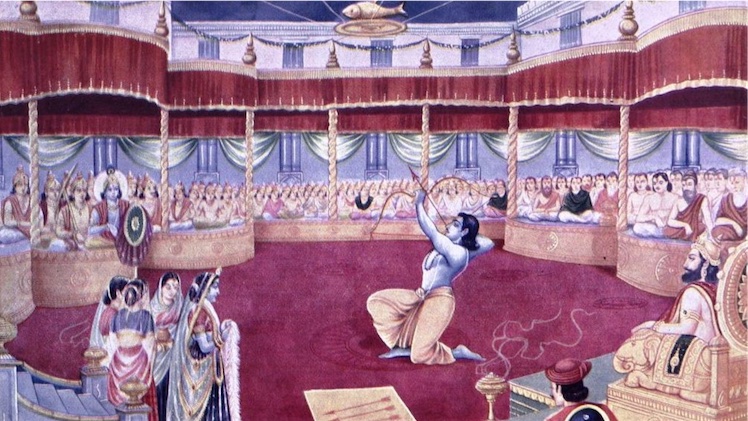

This vision is evident in a sweet story associated with the Ramayana. When Rama’s monkey-assistants were working energetically to build a bridge across the ocean, a small squirrel felt inspired to pitch in. She carried a few lumps of earth on her back and placed them on the bridge. Some monkeys wanted to tell her to get out of their way. They felt that her contribution was too tiny to be worthwhile. She would just come in their way as they raced about carrying huge boulders that contributed tangibly to the bridge.

Rama stopped the monkeys from shooing away the squirrel. He told themhe valued her contribution as much as he valued theirs, for he saw the quality of the contribution more than the quantity. Qualitatively, they both were working with the same desire to serve. Quantitatively, the squirrel’s capacity was much smaller than that of the monkeys. But Rama appreciated both because they were doing their best according to their capacities.

This story demonstrates that the Lord acknowledges and appreciates our contributions, even if they don’t seem noteworthy or even noticeable in the world’s eyes. By fixing our vision on him instead of on the world, we can base our self-esteem on a foundation steadier than recognition by a fickle world. Being thus freed from the insecurity and negativity that chokes our contributions, we can strive enthusiastically to become our best.

Our gift to God

Actually, we can’t give any gift to God because he is the proprietor of everything, as the Gita (05.29) reminds. Whatever we may give him belongs to him; it is only temporarily in our possession.

Still, the bhakti tradition recommends that we express our devotion to God by offering him the things we have received from him. This spirit is seen in the widespread cultural practice of the devout prayerfully offering the Ganges handfuls of water taken from the Ganges itself. In such offering, the content of the gift is not as important as the intent: the humble desire to express our reverence, gratitude and devotion.

Krishna highlights this primacy of intent in the Gita (09.26). He declares that he is satisfied with simple offerings – just a leaf, a flower, a fruit or even a little water – when these are offered with devotion. In keeping with this devotional mood, we can reinvent our work as our gift to God and offer its fruits to him. Srimad-Bhagavatam (11.2.36) urges us to offer for the Lord’s pleasure all our faculties – body, speech, mind, senses, intelligence, whatever we have according to our nature.

How our vocation can become a gift to God is seen through the example of the Gita’s original student, Arjuna. He was the best archer of his times. And he became the best not just by his innate talent, prodigious as it was, but also by his unparalleled commitment. While he was studying at his martial teacher’s academy, whatever he was taught during the day, he would practice that late into the night. By such diligence, he became proficient in various extraordinary archery skills such as hitting invisible targets just by hearing their sounds. Thus, he became an eminently competent instrument in Krishna’s hands. When Krishna wanted to establish dharma, a cause that required fighting an epic war, Arjuna was competent to serve as Krishna’s foremost agent.

Unlike Arjuna, we may not have avenues for directly serving Krishna through our vocations or avocations. Still, we can hone our abilities and make positive contributions in our sphere of influence, knowing that Krishna can open opportunities for service anytime, anywhere, anyway. After all, Arjuna too did not know in advance that his archery skills would enable him to play such a crucial role in Krishna’s plan. He honed his martial skills tirelessly because that was his nature and his duty. And, in due course, Krishna arranged for those skills to be used gloriously in his service.

Ultimately, the gift that Krishna wants most from us is not what we do, but what we become – how we evolve spiritually. Whatever we do in this temporary world will be temporary. But in striving to do it in a devotional mood, we can purify our heart, making it a suitable place for him to manifest his all-pure, all-attractive presence. When we become attracted to him, we attain his abode, never to return to this mortal world, as the Gita assures repeatedly (04.09, 08.15, 08.21, 15.06).

All-round growth

When we strive to serve in this world,various challenges will obstruct us. Still, just as gold shines brighter when passed through fire, so too does our spirituality shine brighter when we persevere devotionally through challenges (Srimad-Bhagavatam 11.14.25).

When we persevere thus, we progress both materially and spiritually. Materially, we do greater justice to our God-given talents and make tangible contributions in this world. And spiritually, we rise in our consciousness and come closer to Krishna and the unending happiness thereof.

Ultimately, this life of love helps us attain the world of eternal love, where we can delight forever with our Lord.