The Power of Saying No

By Chaitanya Charan Dasa | Июл 04, 2009

“A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.” – Henry David Thoreau

In the 1960s, psychologist Walter Mischel and others started a revealing study of four year old children at a preschool on the Stanford University campus. The four-year-olds were offered a proposal involving getting a marshmallow (a kind of sweet candy). If they could wait for about twenty minutes till the person giving the candy returned after doing a small task, they would get two candies. If they couldn’t wait till then, they would get only one candy – but they would get it instantly.

Most of the children impulsively grabbed the candy as soon as the experimenter left the room. A few four-year-olds were able to tolerate what must have seemed to them an endless wait. They sustained themselves by covering their eyes so as to not see the temptation, or rested their heads in their arms, talked to themselves, sang, played games with their hands and feet, even tried to go to sleep. These determined children eventually got their two candies.

When these children were tracked down as adolescents, the difference between the two groups was dramatic. Twelve to fourteen years later, those who had resisted the temptation at four were:

- Less likely to go to pieces, freeze or regress under stress

- Less likely to become rattled and disorganized when pressured

- More able to pursue challenges instead of giving up

- More self-reliant and confident

- More trustworthy and dependable

- Capable of taking initiative and diving into projects

- Still able to delay gratification in pursuit of their goals

In adolescence, those who had grabbed the candy at four were:

- Easily upset by frustrations

- Prone to think of themselves as “bad” or unworthy and become immobilized by stress

- Likely to be stubborn or indecisive

- Prone to be mistrustful and resentful about not “getting enough”, leading to jealousy and envy

- Likely to overreact to irritations with a sharp temper, thus provoking arguments and fights

- Still unable to put off gratification.

When they were again tracked down while finishing high school, those able to wait at four were far superior as students than those who had acted on whim. According to their parents’ evaluation, they were better able to:

- Put their ideas into words

- Use and respond to reason

- Concentrate on the work at hand

- Make plans and follow through on them

- Learn new things with eagerness

Most astonishingly, those self-restrained at four had SAT scores averaging 210 points higher than those impulsive at four.

Summarizing the results of this study, pioneering psychologist Daniel Goleman in his book Emotional Intelligence remarks, “There is perhaps no psychological skill more fundamental than resisting impulse.”

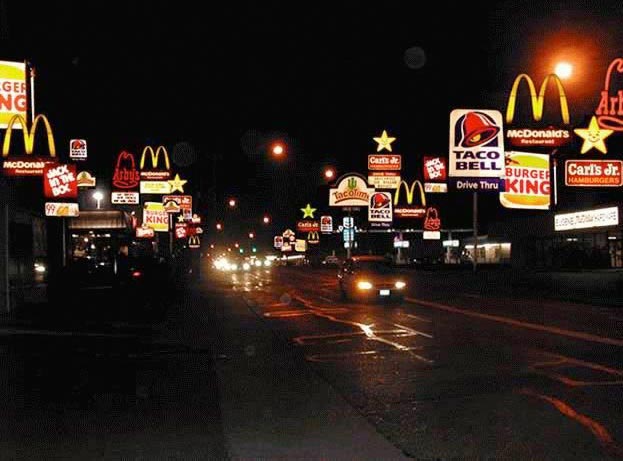

In striking contrast to the skill of resisting impulse, today the ability to act on impulse is celebrated as the proof of “freedom”. Indeed, total obedience to one’s impulses (“I do what I want when I want the way I want”) is portrayed by many as liberating. But is it liberating to be controlled by one’s impulses? Not at all. In fact, it’s binding, not liberating. Because the more we obey our impulses, the more they control us and take away our freedom to make intelligent choices.

Unfortunately, not only do a lot of people give in to their impulses, but they feed and fan their impulsive greed, thinking that they are being “ambitious”. Here’s an example to expose this notion of ambitiousness.

Imagine a weightlifter capable of lifting 25 kg weight “ambitiously” picking up a 100 kg weight. Does his ambition lead him to success? No. It simply gets him injured, maybe even crushed under the weight.

Similar is the modern, materialistic notion of ambition – it’s simply the recipe to hurting ourselves, even crushing ourselves, with anxiety. “Live for the moment” is a typical modern mantra. But after the moment ends, as it surely does – and often too soon – we then have to live with the reality of a huge financial burden. Not for just a moment but for perhaps a whole lifetime.

Contrast this modern notion of ambitiousness, which the west has exported to the world, with the guideline on lifestyle management of one of America’s founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin: “Better to sleep hungry than to wake in debt.” Almost all ancient wisdom-traditions echo this advice to live within one’s means. Consider the following traditional sayings:

“Those who buy things they don’t need will soon have to sell things they need.”

“Don’t save what remains after you have spent; spend what remains after you have saved. “

To some, such advice may seem pathetically anti-progressive. Such people have short memories. They forget that for centuries most people worldwide lived without stress because of choosing to live within their means. In the past, people would fear taking a loan unless it was essential for their very survival. They would choose simplicity with the peace of mind that it brings over luxury with the anxiety that it brings.

Of course, we need not be entirely ambitionless, but we need to calmly and clearly differentiate between realistic ambition and foolhardy ambition. For the 25 kg lifting weightlifter to suddenly want to lift 100 kg is foolhardy; to want to lift a 30 kg weight is realistic. By being realistically ambitious, he may eventually be able to lift 100 kg too – without injuring himself. Similarly, for a person with a salary that affords a two bedroom flat to purchase a big bungalow on credit is foolhardy, though he may well be able to purchase it after some years if he progresses patiently and realistically.

The Vedic culture is centered on empowering everyone to become resistors instead of grabbers not just in the materially beneficial sense indicated by the above Stanford survey, but also in the sense of the willingness to wait for long-term spiritual fulfillment instead of instant sensual gratification. Perhaps if the recession and its aftermath can prompt more people to resist being mindless grabbers, impelled by the media and the culture and become thoughtful resistors – materially and spiritually, then the recession can well become an opportunity for personal growth and empowerment.

(Adapted from the author’s book “Recession – Adversity or Opportunity” available on lulu.com)