To Boldly Go Where We’ve All Gone Before

By Ravinda Svarupa Dasa | Май 23, 2009

Star Trek, the franchise that never dies, has, like the vampire, returned among us, this time in a clever “prequel” to the original ’60s space opera TV series. In this, the eleventh of the series-spawned feature films, Kirk, Spock, McCoy and the other starship Enterprise voyagers appear as “sexy young cadets,” as David Hajdu describes them in his illuminating op-ed piece on the “Star Trek” phenomenon in last Sunday’s Times.

I confess to having been utterly underwhelmed when the original series debuted back in 1966. I didn’t watch the show regularly—I didn’t even own a TV set—but what I did see made me wonder at the enthusiasm of some acquaintances (who apparently sustained the franchise for years to come as Trekie cultists).

The most disheartening feature of the TV episodes was, to me, its utter failure of imagination. The program’s now-famous slogan “To boldly go where no man has gone before” promised wonders that the series itself consistently failed to deliver. The strange new worlds, the alien civilizations so remote they were accessible only by faster-than-light travel, turned out to be uncannily like familiar earthly culture of the past, such as ancient Rome or Egypt, or the American old West, the Berlin of the 1930s, and so on. Focusing on this odd feature of the original series, Hajdu, a professor at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, unveils the truth: “‘Star Trek’ was, from the start, more nostalgic than futuristic.”

The original series was never really about the 23rd century or outer space; and to think of it only in those terms is to misunderstand the show and ignore its real legacy. Despite its technological gimmickry — the flashing light bulbs and the transporter beams and the cafeteria dispenser that synthesizes the atomic structure of any lunch order — the series was essentially a trek around the past, and not even the real past, but the past of vintage Hollywood movies. Its fictions always had less to do with science than with popular entertainment itself.

Hajdu goes on to point out that in the sixties TV networks found they could satisfy their growing audience cheaply by filling up airtime with old Hollywood movies. I can personally vouch for what Hajdu says:

Thus, the children of the ’60s became the first generation to grow up on the whole catalog of American movies, not just the films of their own day; they were the first to have a free education in pop history and to develop a hardy appetite for kitsch.

It was this taste for an illusory past, for a Hollywood-manufactured past, for history as kitsch, that “Star Trek” aimed to satisfy. Hajdu does more than present an acute cultural and historical perception. His research turns up a smoking gun: The pitch for “Star Trek” that Gene Roddenberry, the show’s creator, presented to the producers—who had become owners of old Hollywood movie lots with their multitude of sets.

“The majority of story premises …can be accomplished on such common studio back lot locales and sets such as Early 1900 Street, Oriental Village, Cowtown, Border Fort, Victorian Drawing Room, Forest and Streamside,” wrote Roddenberry in his original pitch. “Interiors and exteriors temporarily available after an ‘Egyptian’ motion picture, a ‘horror’ epic, or even an unusual telefilm, could be used to meet the needs of a number of story premises.”

Hajdu concludes:

The creative re-use of studio sets may have begun as a way to keep costs down. But the show made a kind of loopy pastiche pulp art by appropriating, referencing and recombining ideas from film history, going imaginatively — and, yes, even boldly — where many had gone before.

One wonders whether life imitated “a kind of loopy pastiche pulp art” when the real America NASA space program expropriated the show’s motto for the title of its account of its most famous venture: Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions. Moreover, as a result of a write-in campaign, NASA named its first Space Shuttle orbiter the , after the famed Star Trek craft.

The Real Enterprise

The Real Enterprise

In the 1960s space exploration was conducted on a number of levels. We’ve just looked at Hajdu’s analysis of the pop-culture space exploration of “Star Trek.” And then there was NASA’s famed effort, another made-for-TV production. All America was glued to their screens in July of 1969 to watch the lunar lander descend and see the suited astronauts bounce across the moon’s dusty surface.

But space exploration meant something else again to thousands of American youth of the time. They had prepared themselves well for the space adventure. And when they gathered before TV screens to witness the momentous event, they enacted their own, parallel, space exploration under the propellant of hallucinogenic doses of acid. NASA was interested in exploring mere outer space. The far more intrepid adventure opened to those who explored inner space.

At the beginning of each episode of “Star Trek,” a voice-over by Captain Kirk intoned the full text from which the series signature slogan was extracted:

Space. . . . The Final Frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.

These were the expectations of all three types of space voyages. In retrospect, we can see that all have let us down. We remain earthbound; our flights—whether of script-writers’ fantasy, or liquid-nitrogen propelled rockets, or pharmaceutically induced transcendence—have left us back where we were before, or in even a worse place, stuck with the same old problems on an even more endangered globe.

Yet there was another adventure beyond earth launched in those days of Star Trek, Apollo project, and LSD. This adventure brought the ancient past together with contemporary efforts and even something of the science-fiction-y future.

“Stay High Forever! No More Comedowns” proclaimed a handbill distributed by the Hare Krishnas in the fall of 1966. An explanation soon followed in Back to Godhead magazine:

The effects of the drugs are only temporary; the drug user is “up” shortly after taking the drug, but after a few hours he “comes down.” Krishna Consciousness teaches how to “stay high forever” without bringdowns, by chanting one’s way into eternity. Nor do drugs free one from material hankerings such as food, sex desires, etc..,but sometimes rather provoke desires.

Some members of the Society experienced psychedelic drugs extensively before meeting Swami Bhaktivedanta, and they now no longer take them. Some consider their previous drug experiences as a kind of spiritual “undergraduate” study and now consider Krishna Consciousness to be graduate school study. Krishna Consciousness teaches one how to swim in the spiritual ocean without water-wings.

It is no coincidence that the ancient Vedic sage Nārada Muni became a favorite and much-beloved figure , among the early counterculture Krishna converts. The reason can be found in the way Prabhupāda had introduced this personage in his first volumes of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, written and published in India prior to his voyage to America. In those pages, the spiritual refugees from both the culture and the counterculture were able to read, in the purport to 1.6.31:

As stated in the Bhagavad-gītā, there are three divisions of the material spheres, namely the ūrdhva–loka (topmost planets), madhya–loka (midway planets) and adho–loka (downward planets). Beyond the ūrdhva–loka planets . . . are the material coverings of the universes, and above that is the spiritual sky . . . . Śrī Nārada Muni could enter all these planets in both the material and spiritual spheres without restriction, as much as the almighty Lord is free to move personally in any part of His creation. In the material world the living beings are influenced by the three material modes of nature, namely goodness, passion and ignorance. But Śrī Nārada Muni is transcendental to all these material modes, and thus he can travel everywhere unrestricted. He is a liberated spaceman.

And (1.13.14, purport):

Nārada is a spaceman who can travel unrestrictedly, not only within the material universes but also in the spiritual universes. Even Nārada used to visit the palace of Mahārāja Yudhṣṭhira and what to speak of other celestial demigods. It is only the spiritual culture of the people concerned that makes interplanetary travel possible, even in the present body.

And (1.13.60, purport):

Śrī Nāradajī is an eternal spaceman, having been endowed with a spiritual body by the grace of the Lord. He can travel in the outer spaces of both the material and spiritual worlds without restriction and can approach any planet in unlimited space within no time. . . . . Because of his association with pure devotees, he was elevated to the position of an eternal spaceman and thus had freedom of movement. One should therefore try to follow in the footsteps of Nārada Muni and not make a futile effort to reach other planets by mechanical means.

The first Hare Krishna artifact I owned, as a matter of fact, was a Nārada Muni black light poster, purchased in a local head shop. On my wall the eternally liberated spaceman shined in vibrating hot-pink within a luminous border, in which the mahā-mantra, sinuous in psychedelic font, pulsed between edgings of psychedelic ornamentation.

A drawing of Nārada Muni also decorated the cover of the first Hare Krishna literature I read, a fifty-cent booklet by Prabhupāda entitled Two Essays, acquired in 1969 from a robed and shaven-headed devotee on a campus walkway.

The spiritual voyage of the devotees was quite consciously intended to supplant all the bold but vain adventures of popular culture, the counterculture, and the military-scientific culture shared by the astro- and cosmonauts of the USA-USSR “space race.”

This vaunted venture into the “new frontier” of space, this “great step for mankind,” was deconstructed by Prabhupāda as an innate spiritual urge misplaced, or displaced, onto the material platform, a deflection of the desire for transcendence that would only result in disappointment. For this reason, he advised, as in the Bhāgavatam text quote above, that we should “try to follow in the footsteps of Nārada Muni and not make a futile effort to reach other planets by mechanical means.”

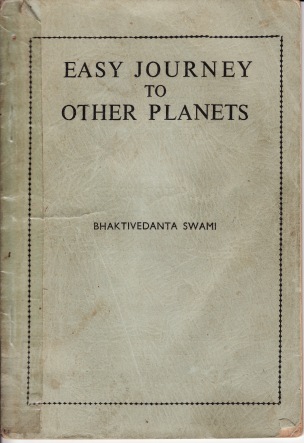

Prabhupāda’s small book on this theme, Easy Journey to Other Planets, was first published in 1960 in India. (Price: 1 Rupee.) There he asserted that, even on the material platform, the ancient civilization of India had perfected a subtler and more advanced form of space travel through yoga:

Even if a materialist wants to enjoy developed material facilities, he can transfer himself to the other many many material planets where he can experience more and more advanced material pleasures. The best plan of life is to prepare oneself for going back definitely to the spiritual sky after leaving this body but yet if anyone wants to enjoy the largest amount of material facilities, one can transfer himself in the other planets, not by means of playful sputniks which are simply childish entertainments but by psychological effects and learning the art of transferring the soul by mystic powers.

Prabhupāda makes the case that all of this is intended to lead us to achieve the highest, transcendent, eternal planet, Kṛṣṇa-loka.

Prabhupāda’s original booklet had a simple cover:

But the illustrated cover of the first American edition made the comparison between the two kinds of ventures explicit:

The most recent edition of the work has a more sophisticate cover, more in keeping with Prabhupāda’s original India title and sub-title, Easy Journey To Other Planets (by practice of Supreme Yoga):

Even after the televised Apollo moon landing of July, 1969, Prabhupāda continued to insist that the moon—richly described in the Vedas an opulent “heavenly planet,” a place of superior sensual happiness—had not been attained by “childish” mechanical means. He offered a variety of possible explanations. It could have been a hoax, the manned moon-landing a studio special effect: Prabhupāda recollected a motion picture depicting a large monkey climbing a skyscraper:

This particular suspicion—which, like Hajdu’s expose of “Star Trek,” invokes images of old movie sets and studio special effects—is not at all limited to Prabhupäda, and proliferating moon-landing conspiracy theories even inspired yet another Hollywood production, the 1978 thriller Capricorn One.

Then again, Prabhupāda suggested in several places in his Bhāgavatam commentaries that the astronauts may have landed on the “invisible planet” Rāhu—the dark, barren, and hostile planet known in modern astronomy as the ascending lunar node. And, in a hypothesis that will conflict the least with the “consensual reality,” Prabhupāda said that the astronauts may have gone to the moon, but that they were unable or forbidden to “enter the atmosphere.” He compared them to illegal immigrants, who arrive in the desired country only to be sequestered in internment camps and then deported.

In any case, the once common phrase “the conquest of space” now reeks of astonishing overconfidence and vainglory. We may poke at it here and there, but “conquer?” We clearly cannot even conquer our own minds.

Those who have, those Vedic travelers with yogic powers like Nārada Muni, on the other hand, also have freely explored both the material and spiritual worlds, and have reported on those places we are restricted from entering.

Or so we hear. Of course, one may well claim that the Vedic tradition’s “easy journey” through “supreme yoga” that Prabhupāda presents is simply one more fantasy of escape and freedom.

Let me just note that modern people have characteristically been quick to deny or dismiss the achievements of ancient civilizations. Our modern mentality remains rooted in the 18th century Enlightenment, with its wholesale rejection of the traditional convictions and practices of the human race, judging them as little more than a mass of error and superstition. Consequently, humanity should start itself over and accept only what it can establish by cool reason and science, unshackled by inherited prejudices. We have long congratulated ourselves on our “progress” so produced.

Of course, the most intractable global problems we face today turn out to be consequences of that progress.

Even custodians of official knowledge have begun to acknowledge that our remote ancestors may have known much more that we have credited them with. Now we find a Ph.D. ethnobiologist from Harvard squatting in remote jungles as an apprentice to a naked and painted shaman in order to learn his pharmacopeia. Pharmaceutical giants seek patents from the knowledge of primitives.

Primitives were not primitive. For example, the abundant evidence is gradually surfacing that pre-Columbian America contained civilizations more populous and in many respects more advanced that those of Europe.

Prabhupāda claims that Śrīmad Bhāgavatam is the product of a far more advanced civilization that ours today. It tells of places and people far beyond the reach of the any Enterprise of “Star Trek” or NASA. It tells of a powerful material and spiritual technology based on mastery of yoga and mantra. Yet “modern man” can hardly be expected to accept it.

Here, for example, is the Indologist Harvey P. Alper, in his introduction to the scholarly collection he edited called Understanding Mantras: “Most of use who study mantras critically—historians, philosophers, Sanskritists—take the Enlightenment consensus for granted. We do not believe in magic. Generally, we do not pray.”

It is time to boldly go beyond the “Enlightenment consensus.” We should become skeptical of the skeptics themselves. After all, no less distinguished an authority than the late Arthur C. Clarke—an author of 2001: A Space Odyssey—has correctly noted: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Who knows? Maybe we’ll all come to set aside “childish sputniks” for the mantras of Nārada Muni.