Along the Banks of a River, the India of Old

By Rosslyn Glassman | Dec 27, 2008

HOWRAH STATION in Calcutta was packed with travelers as I arrived to catch the 3:30 p.m. train to Jangipur. Passengers and porters charged in all directions, some carrying their suitcases or cloth bundles in their hands, some with their baggage on their heads. One man with a chair; another with a stepladder. At my feet, someone was charging his cellphone on the station’s electricity supply. Our train drew up, and the man next to me suddenly threw himself head first through an open window. With his feet waggling, he was stuck until a friend pushed him through. Luckily, I had reserved seats, so I was able to enter through the door and then settle in for the five-hour journey through eastern India.

A few weeks earlier, I had booked a river cruise on the Hooghly, a tributary of the Ganges that runs south through West Bengal, past Calcutta and out to the Bay of Bengal. I was one of 14 travelers — 13 Britons and one American — who had signed up with Assam Bengal Navigation with the hope of seeing India at its most rural. (I was there in late June, well before the recent attacks in Mumbai, a horrific event that should sadden anyone who loves India as I do.)

It was monsoon season, which promised drenching rains every afternoon, but none of us seemed to mind, and I had come prepared: a raincoat, an umbrella and waterproof shoes were all in my luggage. Plus, the Hooghly is navigable only when summer rains swell its banks.

The boat journey could not begin immediately. Our boat, the Sukapha, was moored 250 miles upriver. But the train ride was itself a journey of discovery. Through the window, rural Bengal flashed past, flat and agricultural. We saw paddies of rice, millet, wheat, jute and sugar cane glistening and shiny from the recent rain — more shades of green than on a paint chart. Farmers were plowing with teams of oxen, women were carrying water from the pumps, and children were returning from school with their books. Cows seemed to be wandering in all directions. “They’re on their way home,” my seatmate said. “They know where they live.”

Sumit Bhattacharyya, our tour manager, met us at the end of our train journeys, and we quickly walked through the town down to the ghat, the flight of steps leading to the river, where a small wooden vessel was waiting to take us out to the Sukapha. In the midst of the river with lights blazing, it overpowered all the local craft, looking rather like a Mississippi riverboat, but without the paddle wheels.

All of us were up on deck long before breakfast on our first morning, wearing robes and holding cups of tea, mesmerized by the life along the river: women dressed in saris washing themselves and their children in the latte-colored water, laundry hanging on trees, fishermen working their boats, farmers bearing produce on their heads and youngsters sloshing about, waving and calling and blowing kisses.

Watching the river life became a pleasantly automatic routine: up on deck at 6 a.m. to find one of the crew emptying a bottle of mineral water into the kettle to make tea (fine Darjeeling or the coarser Assam) and then into a lounger to gaze at the scenery as we puttered past.

At Baranagar, a tiny hamlet, we saw life as it must have been forever. We saw women in saris making cowpats for fuel, metal workers tapping at pots, mustard seeds being ground, oxen working. As I walked through the village, mothers would whisper to their toddlers, “Say hello to Auntie.”

A group of children followed as we went to see three superb miniature terra-cotta temples from the 18th century, built with curved roofs following the shape made by bending sticks of bamboo. The decoration of scenes from the lives of gods and kings were still in fine condition. A little girl in a party dress whispered to the tour manager that she wanted to dance for us. She started into a raunchy Bollywood routine that took our breath away, gave us a poem she’d written and then ran off laughing. Not to be left out, other children started, shyly at first, to give us flowers. Then becoming bolder, they asked to have their photos taken for the fun of seeing themselves on our digital cameras.

“What’s the National Gallery doing here?” we wondered as we approached Murshidabad, the 18th-century capital of Bengal. After the British had taken all administration to Calcutta (today, Indians prefer to call the city Kolkata), and with nothing to do, the nawabs had gone on huge spending sprees. The Palace of a Thousand Doors, now a museum, proved to be an exhausting mishmash of antiques, collectibles and armor. The royals had commissioned dozens of paintings, mostly of themselves — one nawab continually appearing in different uniforms and in garb that looked suspiciously like Edmund Kean’s costume for “Richard III.”

Later that day, on our first bicycle rickshaw ride, we set out in convoy to visit two merchant houses, and a tomb a little out of town. It was a fabulous way to see the countryside, and as people waved as we went by, we realized how rare tourists still are in this part of India. With not a postcard or T-shirt anywhere, what we were seeing was true.

It was all action in Murshidabad that afternoon. A Bollywood soap was being filmed, and the whole town seemed to be out on the road. Even at dusk, the crowd stayed on the ghat to greet us. Smartly dressed parents brought their children in what looked like their best clothes to say hello. That night two members of the family of the nawab of Murshidabad came on board for drinks, closing with a flourish a wonderful day.

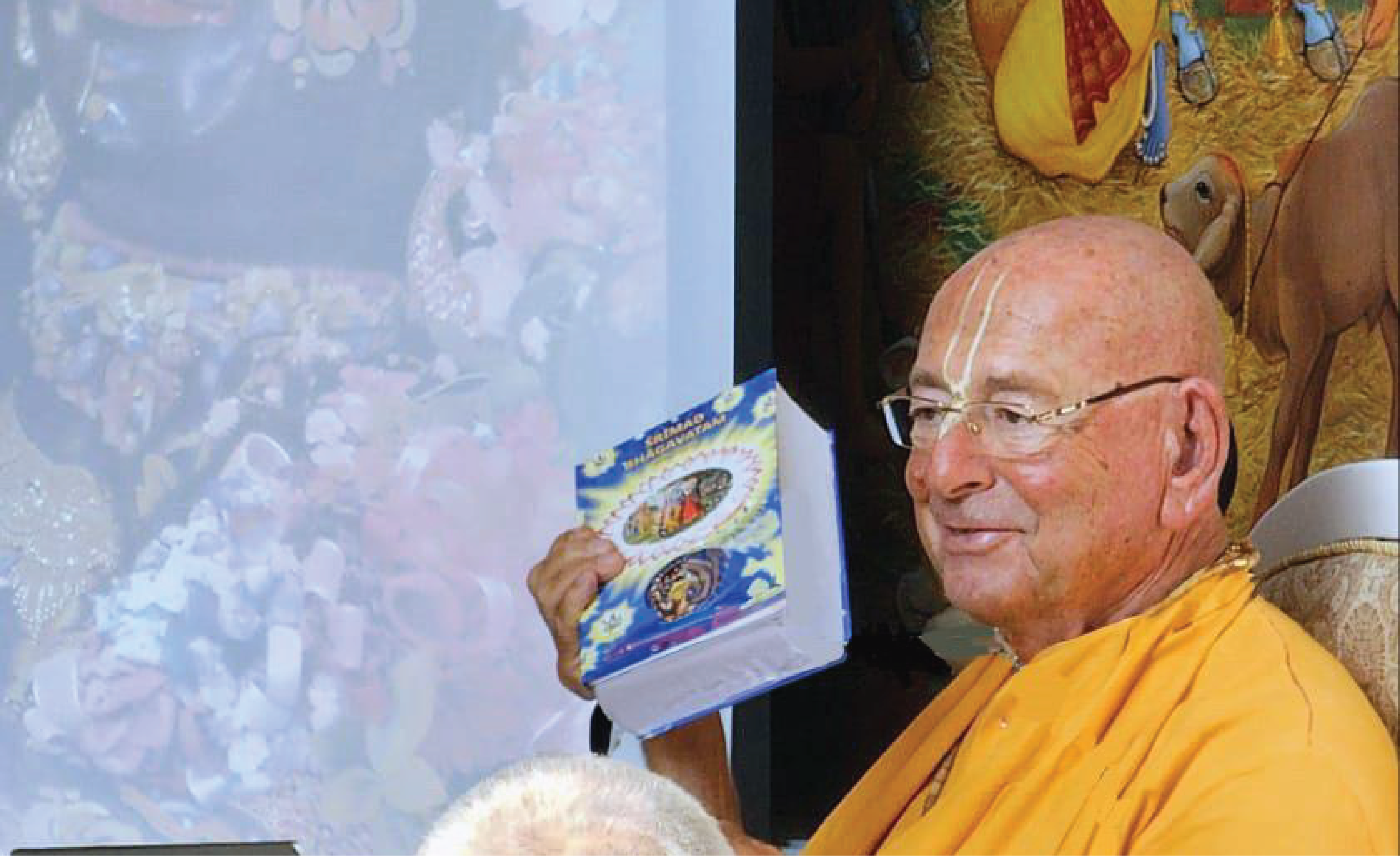

In the following days, we stopped in at Plassey, the site of the pivotal battle of 1757, in which Robert Clive defeated the last nawab of Bengal, and the village of Matiari, a community of brass workers, who at a little foundry poured sacks of gold-colored keys, padlocks and bits of metal on the ground like treasure all to be melted down and then made into more of the same. In neighboring Katwa, we saw walls painted with red hammers and sickles, reminding us that the state of West Bengal currently has a Communist administration. In Mayapur, downriver, we visited the huge headquarters of the International Society of Krishna Consciousness, where a long stream of saffron-robed devotees chanting “Hare Krishna” passed by, except for one follower bizarrely dressed as Elvis Presley.

Our last visit to a Hindu temple was at Kalna, with its grouping of 108 Shiva temples in two concentric circles, the outer of 74, the inner 34. “Life is circular,” a priest explained. “What begins, ends and begins again, like the beads on a rosary.”

Our final stop was Barrackpore, or Barracktown, the site of the oldest cantonment in the country and a welcome weekend retreat for British Calcutta. It was here in 1857 that Mangal Pandey was hanged, becoming an early martyr of the first war of Indian Independence. About a century later, the British went home.

And so, a day later on our trip, did we. But not without a longing to return as soon as possible.