Judgment Eclipsed

By Sesa Dasa | Aug 01, 2009

Judging others is always tricky. Much of what we do, say, or believe is based not on objective truths, but rather on the relative value we place on a particular activity, thought or behavior. Yet, judgment or discrimination is a necessary function in our lives. So, perhaps the best way to judge someone or something is to evaluate the person or the activity in terms of the values or standards they set for themselves.

Following this approach, and given the self-imposed standards of journalism espoused by the Christian Science Monitor, I was disappointed by the July 21, 2009 Global News Blog posted by Staff writer Dan Murphy that was essentially a 450 word dismissal of thousands of years of Indian culture.

Here’s what the Christian Science Monitor says about themselves:

Who we are, what we stand for

The Monitor is recognized for its balanced, insightful take on the news, and for the fresh, independent voice it offers.

Just what distinguishes the Monitor from the countless other news outlets that provide news and information today?

Reporting that offers clarity, context and compassion. [Emphasis their own]

Monitor reporters are highly principled, professional journalists who look beyond the headlines to analyze how events affect individuals and communities around the globe and in our own backyards. The Monitor profiles those who are seeking solutions to problems and appeals to those who value our mission of unselfish service. The Monitor cares about people, and in turn offers a vibrant forum for people who care.

Compare this standard of journalism to Murphy’s article which begins with the pejorative title, “Eclipse? India says demons and terrorists and floods, oh my,” then characterizes “millions of Indians” as fearful, superstitious, and subservient to a “darker side” of astrology, and concludes by slamming the door in the reader’s face with the conversation ending condemnation, “On Wednesday, Hindu temples will be closed, and won’t be open until after they’ve been “cleansed.” The planetariums and observatories will be open. That sort of says it all.”

Is Murphy’s article balanced? Murphy may claim balance in that the article sets the Indian believer versus the Indian rationalist. “Believer” is my word, a word I consider to be more balanced. Here is Murphy’s polarizing language comparing the two sides, “To be sure, Indian’s critics of superstition [emphasis added], locally known as rationalists, have also been out in force in the nation’s press in recent days.” This so-called superstitious versus rational balance is further thrown off kilter when Murphy uses 100 of his 450 total words to quote the views of an adherent to the rationalist view. The article contains no quotes from the believers.

Well, is there some relevant balancing information, you may ask. Not hard to find if you are really interested in balance, is my response. Comment on the Jyotir Veda, the ancient Indian Science of Astrology/Astronomy, is plentiful and is both thoughtful and scientific in its approach to the subject of eclipses.

In his 1989 book, “Vedic Cosmography & Astronomy,” Scientist Richard L. Thompson, wrote of his mathematical explorations into the science of eclipses from both the modern scientific and ancient Indian traditions:

“In the Vedic literature it is often mentioned that Rahu causes solar and lunar eclipses by passing in front of the Sun or Moon. To many people, this seems to blatantly contradict the modern explanation of eclipses which holds that a solar eclipse is caused by the passage of the moon in front of the Sun and a lunar eclipse is caused by the Moon’s passage through the Earth’s shadow. However, the actual situation is somewhat more complicated than this simple analysis assumes.

The reason for this is that the Surya-siddhanta [A Sanskrit Hindu Text of Astronomy dating back over one thousand years] presents an explanation of eclipses that agrees with the modern explanation but also brings Rahu into the picture. This work explicitly assumes that eclipses are caused by the passage of the Moon in front of the Sun or into the Earth’s shadow. It describes calculations based on this model that make it possible to predict the occurrence of both lunar and solar eclipses and compute the degree to which the disc of the Sun or Moon will be obscured. At the same time, rules are also given for calculating the position of Rahu and another, similar planet named Ketu. It turns out that either Rahu or Ketu will always be lined up in the direction of any solar or lunar eclipse.”

Is Murphy’s article insightful? Seems to me that readers might just be interested in knowing a little more about how all this got started. No doubt superstitions and rituals tend to develop over time in all human endeavors, including astrological practices in India, but an insightful person looks beyond the superficial practices to the origins of those practices. Murphy’s rationalist mouthpiece even refers to “Three thousand years of lived tradition,” but Murphy settles for mediocrity as he fails to pursue this line of investigation in his article.

Were the astrologers of old merely fear-mongers, interested only in subjugating the people as is implied in Murphy’s article? As a reader I can only assume this implication because Murphy offers neither historical nor any other context for his presentation of Indian astrological practices.

Dr. B. V. Raman (1912–1998) was a world renowned astrologer and author. He was a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, London, and a Member of the Royal Asiatic Society. Dr. Raman had influenced the educated public and made them astrology-conscious. His special fields of research were Hindu astronomy, astro-psychology, weather, political forecasts, and disease diagnosis. He was a widely traveled man and addressed elite audiences almost throughout the world. Dr. Raman provides this context to the strictures recommended by astrology in his Book, Muhurta (Electional Astrology), “The ancients studied sciences and laid down strict injunctions so that humanity may be benefited. They did not believe in simply cataloguing facts as we in modern times do. These may be sour grapes for those who are blinded by thick prejudices but they are sweet for those who have a clear mental vision and who wish to economise the waste of spiritual energy for their own ultimate good.”

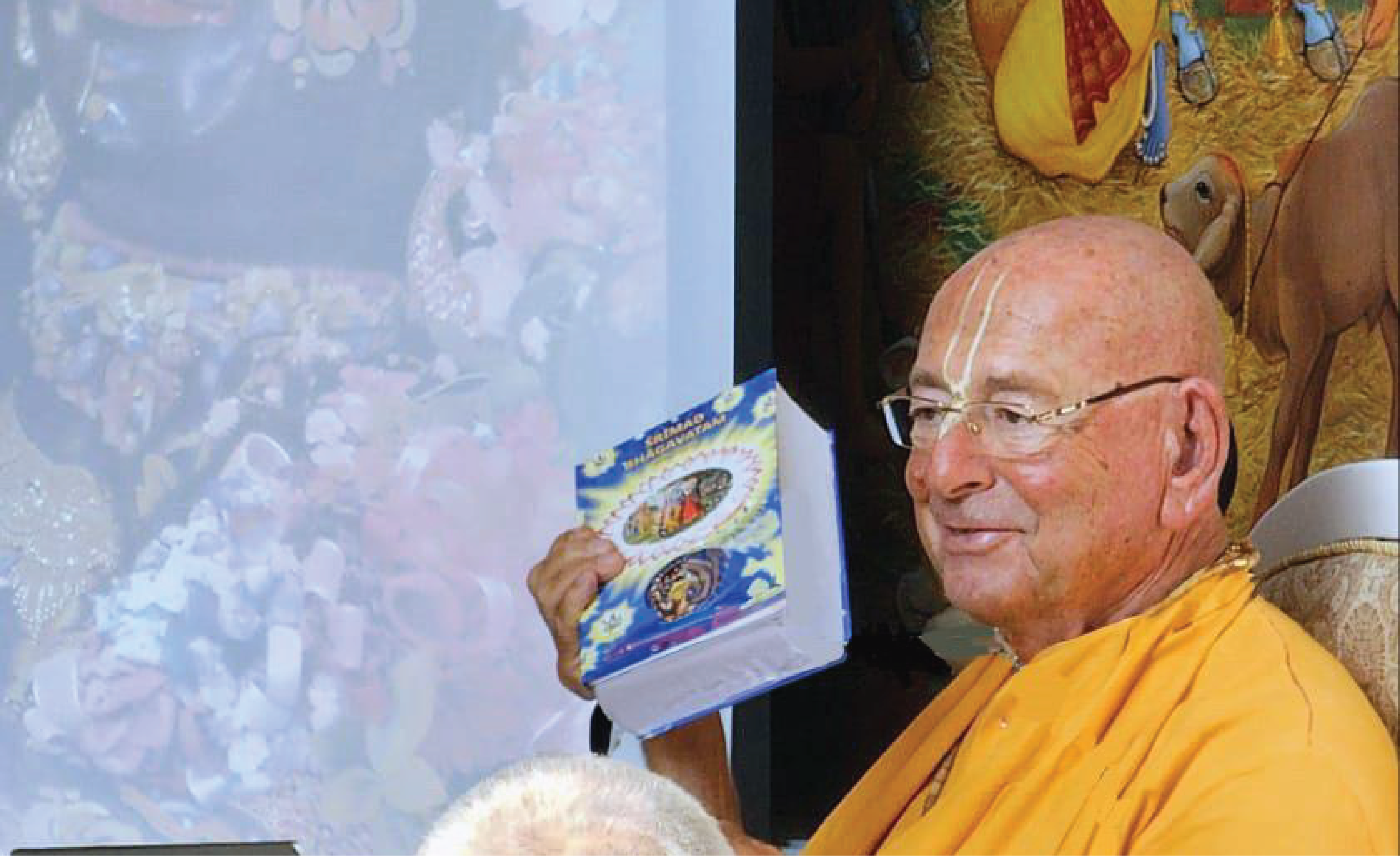

Srila A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Founder-Acarya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness had this to say about the motives of those giving astrological advice in his commentary to the Sri Caitanya Caritamrta:

“Brahmanas generally used to become astrologers, Ayur- vedic physicians, teachers and priests. Although highly learned and respectable, such brahmanas went from door to door to distribute their knowledge. A brahmana would first go to a householder’s home to give information about the functions to be performed on a particular tithi, or date, but if there were sickness in the family, the family members would consult the brahmana as a physician, and the brahmana would give instruction and some medicine. The brahmanas who went door to door as if beggars had perfect command of such vast knowledge.

Thus the highest knowledge was easily available even to the poorest man in society. The poorest man could inquire from an astrologer about his past, present and future, with no need for business agreements or exorbitant payments. The brahmana would give him all the benefit of his knowledge without asking remuneration, and the poor man, in return, would offer a handful of rice, or anything he had in his possession, to satisfy the brahmana. In a perfect human society, perfect knowledge in any science — medical, astrological, ecclesiastical and so on — is available even to the poorest man, with no anxiety over payment. In the present day, however, no one can get justice, medical treatment, astrological help or ecclesiastical enlightenment without money, and since people are generally poor, they are bereft of the benefits of all these great sciences.”

Finally, was Murphy’s article compassionate? Compassion is perhaps the most important value in journalism. In terms of journalism compassion means to be balanced and insightful in one’s reporting. Compassion doesn’t mean to hide or to sugarcoat the truth, but without doing a thorough job by being balanced and insightful, the journalist risks portraying his or her subjects as objects of prejudice and ridicule. Prejudice and ridicule are written all over Murphy’s article.

Thus, by the Christian Science Monitor’s own standards, Murphy’s sweeping generalizations are a disservice to his readers and to the people of India, believers and rationalists alike.