My Lifestyle Is My Protest

By Satyam Kaswala | Dec 24, 2010

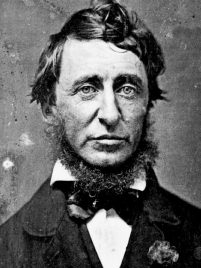

“No truer American existed,” declared the inimitable Transcendentalist writer and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, “than Henry David Thoreau.” Indeed, of all the voices of American history, none speaks to me louder than Thoreau’s. For in my mind, he accomplished no less a feat than making the Vedic-inspired, divine philosophy of simple living and high thinking, and of unfaltering, intransigent devotion to both souls that comprise the Self, something fiercely American. In an age of staggering industrialization, religious devotion to the deities of modernity and capitalism, rapidly changing social mores, and spirited fervor for societal reform, Thoreau understood that this expansion of civilization and American culture, no matter how greatly forward-thinking and progressive, was only external. And he knew that it was ultimately meaningless if individuals within society did not reform themselves internally first. What others viewed as material growth, he viewed as spiritual distraction.

But Thoreau not only articulated the futility of building a fledgling nation on a foundation of superficial culture, or being enslaved to what his fellow citizens, country, or society deemed to be success or happiness; he used his very lifestyle as a protest against them in his fearless pursuit of authenticity. The Walden wilderness where he famously lived for two years was more than a metaphor. It was a living, breathing example of God’s tangible manifestation in nature and within the lives of those who seek Him by not being too afraid of solitude- from the incessant barrage of distractions that characterize modern living- to enjoy the spiritual introspection it allows.

Consider his mystical description of his Walden stay: “Both place and time were changed, and I dwelt nearer to those parts of the universe and to those eras in history which had most attracted me. Where I lived was as far off as many a region viewed nightly by astronomers… I discovered that my house actually had its site in such a withdrawn, but forever new and unprofaned, part of the universe.”

One needn’t retreat to the foreign woods to find truth, for herein he declares that for most people, the farthest and most foreign place in the universe is within their own selves, within their own souls, “forever new and unprofaned.” By shedding off the multifarious layers of daily existence until he could experience life solely in its basic essentials, he tapped into the eternal. As in the seemingly terrifying silence of solitude and simple living, one can not only hear the quaint cries of the soul, but listen to them. Thus he could dwell to any part of the universe and to any riveting era of history free from the constraints of circumstantial time and place, as the mystic yogis do, through the purification of consciousness his pursuit of authenticity enabled. Away from the chaos of society, the American wilderness, a projection of the internal wilderness of the soul wherein God resides, became his cathedral, church, and temple.

That Thoreau rejected the notion that man’s primary fulfillment and greatness and superiority comes from his bodily culture, in a nation built upon the very idea that our primary identities are our cultural ones, hence becoming a “melting pot,” is altogether remarkable.

Yet though his lifestyle was his protest, he seemed to be fueled by something more than mere aversion, disgust, or defiance. How else could he have so deeply experienced the cosmic permanence of nature’s love? He felt her swimming in his blood. He was drawn to something greater rather than simply being repelled from something lesser.

And he was the first to acknowledge what that higher energy was- that the effervescent, magnanimous song that was his American understanding of existence was written in vein of the same spirit that wrote the Vedas. He was not afraid to try to understand God. As he writes in one celebrated passage in Walden,

“Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavat Gita, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma, and

Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the River Ganga reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water—jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganga. With favoring winds it is wafted past the site of the fabulous islands of Atlantis and the Hesperides, makes the periplus of Hanno, and, floating by the Ternate and Tidore and the mouth of the Persian Gulf, melts in the tropic gales of the Indian seas, and is landed in ports of which Alexander only heard the names.”

“The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganga.” This beautiful metaphor is to me the significance of Thoreau’s pursuit. He represents an important- no, a vital- link between the rugged individualism that defines that mystical, fervently defended trait called Americanism, symbolized by Walden pond, and a spiritual, authentic, Vedic way of life, symbolized by the sacred water of the Ganga, that knows that true individualism is understanding the soul only as a door to the Super-soul. Individualism for individualism’s sake is meaningless. Yet by using the individualism championed by America not as a political trope, but as a transcendental vehicle to reach God through a personal path, and recognize Him dwelling, even physically, in all things, he showed that despite our bodies, our cultures, our beliefs, or our religious labels, the blood that flows like rivers in each of us and binds us all together is non-different than Mother Ganga’s water.

“All I have seen,” Emerson concluded, “teaches me to trust the Creator for all I have not seen.” This trust cannot be built by conflating the complexity of civilization and the cultures within it with the progress of individual consciousness. Because ultimately, no nation or skin or era can blind us from this personal vision.