Parasurama Dasa: Food For All, And All For Free

By Madhava Smullen | Oct 25, 2008

At 6.30 in the morning, six days a week, Parasurama Dasa and his Food For All team start cooking for 800 people. By 11am, the feast of rice, dahl, subji, salad, cake and juice is ready to be transported from Bhaktivedanta Manor to London. There, it’s loaded onto bicycle rickshaws and delivered to 600 students and 200 homeless people around the city. Parasurama then spends the rest of his afternoon picking up vegetables from local supermarkets and cleaning his van.

“It’s all I do,” says Parasurama, who doesn’t get paid a penny as director of Food For All and works nights as a security guard to pay his bills. But he sounds bright and enthusiastic; quite unlike someone for whom the existence of a regular full night’s sleep seems dubious. “The other 12 – 14 staff are volunteers too. They’re doing it because they love it,” he explains, “And that creates a very nice atmosphere.”

Food For All has its roots in 1987, when Parasurama and his friends would serve homeless people left-over prasad (sacred food offered to God) from Govinda’s restaurant on Soho St. The project moved to Bhaktivedanta Manor in 1991, and by 1998 Parasurama had registered it as a charity to ensure a more effective operation. Today, Food For All is funded by donations and government grants, and has recently gained support from London Council.

This is no coincidence. Over the years, Food For All has won the love and approval of Londoners through its consistently dedicated service. “We realized how much we were valued when we started serving prasad at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), and the school’s cafeteria tried to get us removed,” says Parasurama. “Immediately, the students boycotted it by eating only our food so that it was making no money at all!”

Management not only relented but gave Food For All a prime spot right at the center of the university. The school now mentions the charity as a dining option in their official handbook, and have fully sponsored them for the past two years. “It’s a big step on from Hare Krishnas being seen as a cult,” says Parasurama.

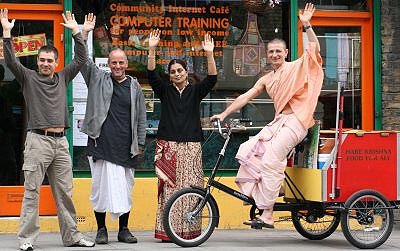

Food For All feeds students of SOAS and one other major London university for free all year around, while their smaller branches in Manchester, Glastonbury, Leicester, and Wales cater to other universities across England. Parasurama encourages others to try it. “It’s an important service because London students are poor, live in a very expensive city, and have to pay for their own education.” He grins – it’s almost impish, and full of refreshing enthusiasm. “All you need to make a difference is a couple of friends who can cook, some rice and subji, and a bicycle rickshaw.”

But Food For All stretches far past being just a food relief project. In 2007, it won London’s Sustainable City Award, considered the green Oscars, for its environmental work. The charity’s eco-garden, where children can learn about the environment, how to recycle, and how to compost using a wormery, is visited by 200 school groups a year.

And this year, Food For All won the Novelis Community Recycling Project of the Year for the entire United Kingdom. “Many major supermarkets and other food businesses throw out perfectly good food because its display-by date is approaching,” explains Parasurama. “We take that food and serve it to students and disadvantaged people, as well as using it for compost. Just two weeks ago, we got three van-loads of muesli that an organic company were going to throw away because it had non-organic apricots in it.”

Being inspired by Krishna consciousness, Food For All also offers options of spiritual discovery with their food. But to accommodate volunteers who hail from other religions, as well as to leave themselves open to outside support — no organization will fund or donate to a religion — Food For All is registered as a secular charity. “Besides,” Parasurama says, “Krishna consciousness is not a religion – it’s the science of the soul.”

Still, Food For All wears its Krishna conscious heart on its sleeve. Devotee volunteers wear tilak and robes; students listen to the Hare Krishna mantra over a sound system as they eat their free prasad; vegetarianism, karma and reincarnation exhibits are on display; and books, such as Bhagavad-gita and the popular Higher Taste cookbook, are available. “After some time, many students take books, and eventually visit Matchless Gifts, our Food For All center,” Parasurama says. “Prasadam breaks down a lot of barriers!”

At Matchless Gifts, Food For All don’t shove Krishna consciousness down anyone’s throat. Their concern is to help people. “We provide free cookery lessons and computer classes to help disadvantaged people get degrees and get on with their lives,” Parasurama says. “But often people who come for those start attending our weekly Friday and Sunday get-togethers. One girl who was taking computer lessons began attending the Friday programs, and is now initiated by Radhanatha Swami.”

The programs draw about fifty, and often feature talks by Prabhupada disciples as well as a delicious feast and “rocking chants” with traditional and modern instruments. Parasurama, if you haven’t guessed yet, finds Krishna consciousness great fun, and wants other people to have the same experience.

He also feels that the best way to make people appreciate Krishna consciousness is not always the most direct way. “When I accepted the Novelis Community Recycling award, I didn’t talk about Krishna or try and sell Bhagavad-gitas to anyone,” he says. “I just accepted the award politely, thanked people and discussed Food For All projects. But I was dressed in full dhoti and tilak despite it being a black tie event. Everyone could see that I was a Hare Krishna, and a completely normal, well-behaved one at that. And I think that was much more effective than anything else I could have done.”

Parasurama has had his fare share of public limelight, with Food For All helping to thwart a recent government campaign to stop feeding homeless people. The campaign objected that many groups kept feeding homeless people, but didn’t do anything else to help them back on their feet. Stop feeding them, the reasoning went, and maybe they’ll get their lives together. But the campaign was stumped when it was presented with Food For All’s day center, computer and cooking courses, drug counselor and other services.

The face-off culminated in a live BBC debate between Parasurama and the leader of the government campaign. “During the debate, three random homeless people were interviewed, all of whom separately said that the Hare Krishnas had saved their lives,” Parasurama recalls. “My opponent had to admit that the Hare Krishnas were different from other groups, and the potential new law was thrown out.”

Live TV shows are not the only adventures the Food For All team find themselves in. They’re a well-travelled bunch, organizing most of the Rathayatra parades in England, as well as an annual five Rathayatra tour of Scandinavia. The small eleven-devotee tour visits Stockholm, Oslo, Copenhagen, and some smaller locations, and is often accompanied by senior monks, including Mahavishnu Swami and Janananda Swami.

Then there’s the two trips a year to India. Food For All’s boat journey, started last year, has become an annual March event. In 2007, five devotees travelled down the Yamuna river from Vrindavana to Mayapur, stopping at Mathura, Agra, Allahabad, Benares, and Patna along the way. “This year, we travelled from Mayapur, through Calcutta, to the ocean on a raft we’d made ourselves,” Parasurama says. “And next year, we’ll start in the Himalayas, and float down through Rishikesh, Hardwar, and other holy places to Kanpur, chanting Hare Krishna all the way.”

When fall comes, they’re off for another trip. For the past twenty-five years, Food For All has toured villages in Vraj (the greater area encompassing Vrindavana) by bullock cart. During their one month tour, volunteers distribute 60,000 books and countless plates of prasad. “We also have a film projector that we charge through solar panels in the roof of the bullock cart,” says Parasurama. “And in the evenings, we hold Krishna conscious festivals and show movies. Many villages don’t have electricity, and it gets dark at six o’clock. So with nothing much to do, everyone comes to our program.”

Food For All also assist villagers in Vraj by digging wells for those without water, a project that international volunteer organization the Lion’s Club recently donated £10,000 to.

Parasurama has devoted his entire life to Food For All, and his love for it is clear. “We all have to do something for Krishna, and this is great fun,” he says. “Every day we’re making so many people happy.”

He adds, “Most people go through some major problems three or four times in their lives. And later, they’ll think about who helped them during that time. Often, it’s the Hare Krishnas.”

Food For All continues to expand. Recently, Parasurama presented an ambitious plan to ISKCON UK managers: He wants ten bicycle rickshaws to visit all the universities in London and distribute 300 plates of Prasad each – adding up to 3,000 plates of Prasad every day.

“If that happens, it could give ISKCON in the UK a big push forward,” he says.