Prabhupada’s Books—The Ultimate Prison Escape Plan

By Madhava Smullen | Apr 05, 2008

ISKCON’s Prison Ministry traces its roots all the way back to 1962, when Srila Prabhupada visited Tihar Prison in New Delhi. “If you give me the chance to speak to all the members of the Jail,” he wrote to superintendent Sri Puri, “It is quite possible for me to turn them into ideal characters.”

Yet it wasn’t until 1988 that Candrasekhara Dasa established the official ISKCON Prison Ministry in the USA, as an outlet for householders to preach without having to leave their homes; all they had to do was write letters. Shyama Priya Dasi, now an IPM volunteer for 17 years, was gripped by the idea of such a personal service the moment she was first introduced to it in 1990. “Chandrasekhara showed me a photo album of all the inmates he was writing to,” she says. “It was like they were family.”

But it was a family of outcasts—rejected by society and abandoned by their friends and relatives. “When inmates read Prabhupada’s books, they realize that although the material world is not what it’s cranked up to be, they’re not alone,” Shyama Priya says. “Krishna still loves them. And that makes them want to change their lives for the better.”

IPM initially sent only a few books to prisons. But when Shyama Priya noticed how often inmates requested them, she began eyeing the full case under her desk. Maybe I could send out the whole thing, she thought, afraid she was being over-zealous. It was an empty fear. Before she knew it, she had sent out thirty cases.

“Prabhupada’s books are the basis of the Prison Ministry,” says Shyama Priya. “We send out 300 Bhagavad-gitas, 200 Science of Self-Realizations, 8,000 small books, and 4,800 Back to Godhead magazines every year.” Now approved vendors in some states such as Texas and Oregon, IPM also sends Bhagavad-gita and Nectar of Instruction correspondence courses to inmates who want to learn more.

And there’s no shortage of students. Although IPM does very little advertising beyond its monthly newsletter Freedom, run by ex-inmate Bhakta Jerry, Shyama Priya receives letters every week from inmates whose lives have been transformed through Prabhupada’s books.

“One woman found an old Bhagavatam in a Louisiana prison,” she says. “She’d never heard of Krishna consciousness before, but she began chanting Hare Krishna and writing to us, and finally got initiated. When her guru visited her in prison, he told her, ‘You don’t belong here.’ She replied, ‘I tried to get pardoned by the governer, but it’s impossible.’ The very next day, she received a letter of pardon from the governor, and was released from prison that summer. She had a 90-year sentence and would have spent the rest of her life in prison.”

Even inmates who don’t have lifelong sentences end up ebbing away their existence in a cell. “Prisons don’t reform,” Shyama Priya explains. “They simply house people until they’re released, commit the same crimes again, and are re-incarcerated. That’s a fact even officials will admit.”

Billing itself as a spiritual reform program, IPM believes its aiming at the root of the problem. “Lord Chaitanya didn’t neglect the most fallen people in society, such as Jagai and Madai—he came to liberate them,” Shyama Priya says. “If inmates get just one Bhagavad-gita, it can change their lives.”

It’s impossible to argue with the evidence. One inmate wrote IPM explaining that he used to be a heavy gambler, drinker and smoker, and that he loved playing poker. Every night he would try to get into the prison poker game, but nobody liked him, and every night he was shunned. Finally, frustrated, he went to the library to get a book instead. He picked out a Western, opened it, and saw to his surprise that it was the Bhagavad-gita—someone had switched the covers. Furious, he began to read anyway, and before long he was gripped. By the time he’d finished the book, he had quit all his bad habits and had started chanting.

But it’s not only inmates who show appreciation for Prabhupada’s books. In 2003, Marty Mendenhall, director of Utah’s largest secure care facility for juvenile delinquents, sent a letter to the BBT that stunned everyone. “We currently have 82 young people incarcerated,” he wrote, “And I would like each of them to have a copy of the Bhagavad-gita. I understand this is a significant number of books to call for; however these young people suffer tremendously and are in dire need of the Lord Krishna’s teachings. If you are unable to send that many copies of the Gita, could you please send any of the writings of His Divine Grace Swami Prabhupada.”

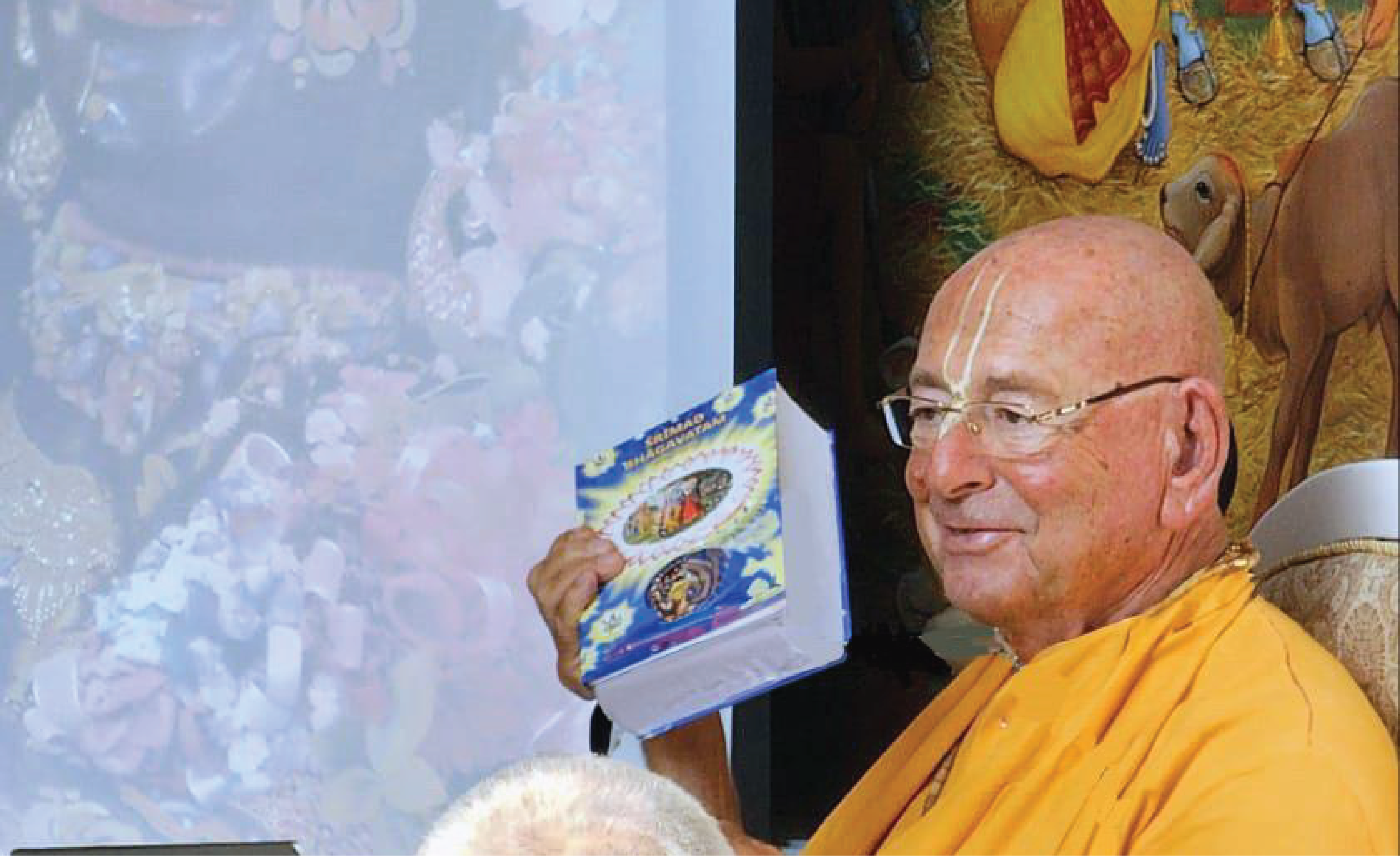

Working solely on volunteer power and donations, IPM hopes to continue its spiritual reform movement. “We’re always looking for more qualified devotees to write letters to inmates,” Shyama Priya says. “And of course, you can donate books through Maha-Tattva’s Sastra Dana program. If we had enough books, we could put full Srimad-Bhagavatam sets in every prison library in America.”

One day, Shyama Priya and Chandrasekhara hope, there will be a prison ministry in every state and devotees visiting prisons across the country. But for now, they’re content with shining a light of hope through cell bars and giving inmates the ultimate chance to break free from the prison of material life—Srila Prabhupada’s books.