Srila Prabhupada and the Sixth Commandment

By Satyaraja Dasa | Feb 16, 2008

At a recent interreligious conference, I happened to mention that we devotees of Krishna are vegetarian, and in the midst of the discussion, I referred to the Sixth Commandment: "Thou shalt not kill." A prominent Christian scholar, who was part of the discussion, asked what the commandment had to do with vegetarianism.

"It has everything to do with it!" I responded. "If you eat meat, you either directly or indirectly kill animals, and killing is what the commandment expressly forbids, isn’t it?"

Well, my Christian friend sharply disagreed. He said that the commandment applied only to human beings. Though he insisted that this was so, he was at a loss for words when I asked him to explain his rationale in this regard. And that got me thinking . . .

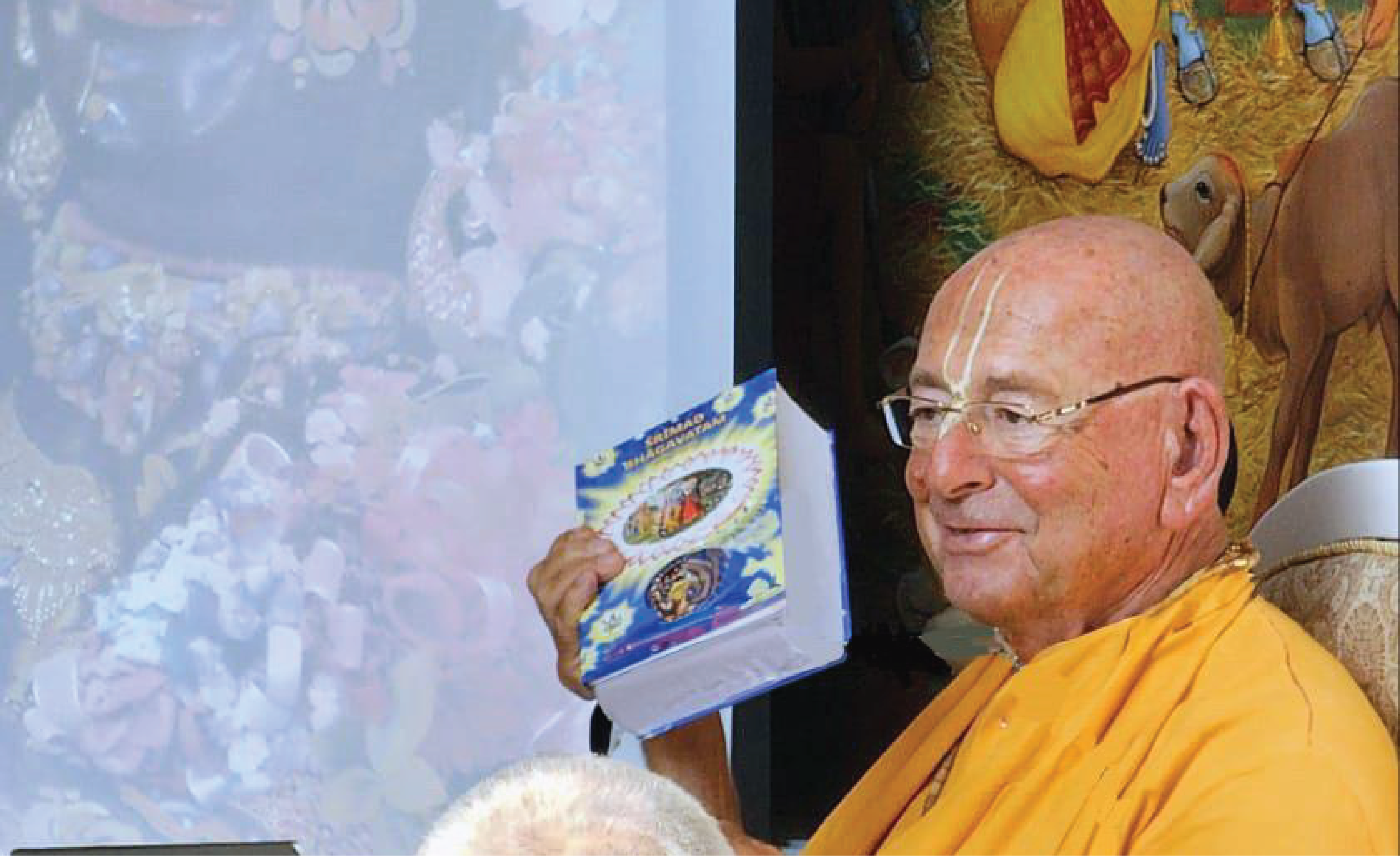

Srila Prabhupada says:

But when you’re actually on the platform of love of God, you understand your relationship with God: “I am part and parcel of God – and this dog is also part and parcel of God. And so is every other living entity." Then you’ll extend your love to the animals also. If you actually love God, then your love for insects is also there, because you understand, "This insect has got a different kind of body, but he is also part and parcel of God – he is my brother." Sama sarvesu bhutesu: you look upon all living beings equally. Then you cannot maintain slaughterhouses. If you maintain slaughterhouses and disobey the order of Christ in the Bible – "Thou shall not kill" – and you proclaim yourself a Christian, your so-called religion is simply a waste of time . . . because you have no love for God.

Prabhupada frequently uses the "Thou shalt not kill" motif in his presentation of Krishna consciousness. It is one of the most persistently recurring themes in his books, and the attentive reader can find reference to it in nearly every one of them.* His insistence on its importance is clear not only from the number of times he refers to it, but from the force and intensity with which he does so. Some examples:

It is not that national leaders should be concerned only with human beings. The definition of native is "one who takes birth in a particular nation." So, the cow is also a native. Then why should the cow be slaughtered? The cow is giving milk and the bull is working for you, and then you slaughter them? What is this philosophy? In the Christian religion it is clearly stated, "Thou shalt not kill." Yet most of the slaughterhouses are in the Christian countries. (From The Quest for Enlightenment, "The Mercy of Lord Caitanya")

They should have been ashamed: "Lord Jesus Christ suffered for us, but we are continuing the sinful activities." He told everyone, "Thou shalt not kill," but they are indulging in killing, thinking, "Lord Jesus Christ will excuse us and take all the sinful reactions." This is going on. (From Perfect Questions, Perfect Answers, Chapter 6)

As far as the Christian religion is concerned, ample opportunity is given to understand God, but no one is taking it. For example, the Bible contains the commandment "Thou shall not kill," but Christians have built the world’s best slaughterhouses. How can they become God conscious if they disobey the commandments of Lord Jesus Christ? And this is going on not just in the Christian religion, but in every religion. The title "Hindu," "Muslim," or "Christian" is simply a rubber stamp. None of them knows who God is and how to love Him. (From The Science of Self-Realization, "What Is Krsna Consciousness?")

Jesus Christ taught, "Thou shalt not kill." But his followers have now decided, "Let us kill anyway," and they open big, modern, scientific slaughterhouses. "If there is any sin, Christ will suffer for us." This is a most abominable conclusion. (From The Science of Self-Realization, "Jesus Christ Was a Guru")

If we look at all of Prabhupada’s proclamations on the subject, the ones that stand out are found in his conversations with two Christian clerics of some renown: Cardinal Jean Danielou, from Paris, and Father Emmanuel Jungclaussen, a Benedictine monk from West Germany. While there is hardly enough space to reproduce these classic talks here, the reader is advised to look through Prabhupada’s book The Science of Self-Realization, where both interviews are reproduced. Briefly, Prabhupada’s main argument is that the commandment should be taken at face value – it is wrong to kill, plain and simple.

Biblical Allowances for Killing

But, those familiar with the Bible might ask, what about self-defense and capital punishment? Or when killing occurs by accident? The Bible makes allowances for these things and thus excludes them from the demands of this commandment. According to the Bible, enemies of Israel can also be killed. So where do we draw the line? If the command does not even include all humans, what hope is there to include animals in its scope?

Given the culture and context in which the commandment was revealed, in all probability it originally meant, "You shall not kill unnecessarily," for, as noted, the Bible clearly permits certain forms of killing. And it probably focused on human concerns rather than those of animals. However, given the ideals of peace and compassion espoused by the Judeo-Christian tradition, it would be natural to extend this command to include the lesser creatures, for modern science – especially the nutritional sciences – indeed teaches that we don’t have to kill animals, even for food. Such foods are no longer deemed necessary for humans to maintain proper health.

Mark Mathew Braunstein, a scholar of some renown, is among those who see in the command a clear ordinance against harming any living beings. He writes, "Moses the messenger brought down the decree ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ Period. While coveting refers specifically to a neighbor’s spouse, or honoring to one’s parents, prohibition against killing is not specific: it says simply and purely not to kill."

This is an important point – the other commandments tell us exactly who falls within their jurisdiction, or who might be deemed their beneficiaries. But here we are simply told not to kill, without any such qualifying considerations.

This, too, is Prabhupada’s argument: If the commandment doesn’t specify whether it is referring to both humans and animals or merely to humans, then why should we interpret it? Why not just understand it in its most simple and direct way? But people do insist on interpreting, and for this reason we will look at the words in question to see if we can find some reasonable resolution to the dilemma.

A Closer Look at the Commandment

If we are to understand Prabhupada’s insistence on "Thou shalt not kill" as a basis for universal compassion and vegetarianism, it is imperative to look at the Sixth Commandment (Exodus 20.13) more closely.

According to Reuben Alcalay, one of the twentieth century’s great linguistic scholars and author of The Complete Hebrew-English Dictionary, the commandment refers to "any kind of killing whatsoever." The original Hebrew, he says, is Lo tirtzakh, which asks us to refrain from killing in toto. If what he says is true, we can analyze the commandment as follows: "Thou shalt not" needs no interpretation. The controversial word is "kill," commonly defined as (1) to deprive of life; (2) to put an end to; (3) to destroy the vital or essential quality of. If anything that has life can be killed, an animal can be killed as well; according to this commandment, then, the killing of animals is forbidden.

The problem is that not all manuscripts of the Bible are the same. Of the numerous references to this same command in the Old and New Testaments, some of are nuanced in slightly different ways. Modern scholarship now leans toward "Thou shalt not murder" as opposed to "Thou shalt not kill." How do scholars come to this conclusion, and what really is the distinction between the two?

First, let us examine what the Bible actually says. The Hebrew word for "murder" is ratzakh, whereas the word for "kill" is haroq. The commandment, in the original Hebrew, indeed states: "Lo tirtzakh" (a form of ratzakh), not "Lo taharoq." In other words, it is "Thou shalt not murder," as opposed to "Thou shalt not kill." Why, then, does Reuben Alcalay say that tirtzakh refers to "any kind of killing whatsoever"?

The Words "Kill" and "Murder" in Biblical Tradition

The difference between these two words – "kill" and "murder" – has more to do with modern usage than original texts: the demarcation between these words may have been different in biblical times. Indeed, the Bible appears conflicted in this regard, as do Bible translators. The HarperCollins Study Bible, which is the New Revised Standard Version and the rendition used by the Society of Biblical Literature, interprets the commandment as "Thou shalt not murder," but it then includes a footnote saying "or kill." The New Oxford Annotated Bible does the same.

The King James Version of the Bible, and others too numerous to mention here, translate the verse as "Thou shalt not kill," while others keep going back and forth, changing from "kill" to "murder" and, every few years, back again.

Perhaps the most important version to use the word "kill" instead of "murder" is The Holy Bible: From Ancient Eastern Manuscripts. This work is based on the earliest editions of the text, making use of rare Aramaic fragments. Here we find that the Exodus verse is unequivocally rendered as "Thou shalt not kill," though a lengthy Introduction explains why well-meaning translators might choose otherwise.

Rabbi Joseph Telushkin writes about one of the many dangers of interpreting the word as "kill":

If the commandment had read "You shall not kill," it would have suggested that all killing is illegal, including that in self-defense. Indeed, certain religious groups such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses take this position, and insist that their members refuse army service (during World War II in Germany Jehovah’s Witnesses refused to fight for the Nazis while their American co-religionists refused to fight against them).

These are very real concerns for biblical translators and commentators, and while they may have diverse opinions on whether to use "kill" or "murder" while addressing any number of complex issues, one thing is certain: In current usage, the two words carry different meanings. According to Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary, "killing" is straightforward, and its definition is given above. But "murder" is more complicated. Webster defines it in legal terms. Its first definition as a noun is "the unlawful and malicious or premeditated killing of one human being by another"; as a verb, it is defined as "to kill (a person) unlawfully and with malice." These are first-entry definitions. If we look at secondary ones, we find "to kill inhumanly and barbarously, as in warfare," or "to destroy; to put an end to."

Prabhupada admits in his conversation with Father Emmanuel that "murder" refers to humans, and this is borne out by the primary definitions given above. But who defines these words? Because animals do not have the same rights as humans, at least in contemporary Western society, they are omitted from the definition of murder – and so it is not considered unlawful to take their lives. But if we look at murder practically – at what it really is, beyond mere legalistic formulas – we are confronted with the secondary definitions of "murder" given above, both of which can certainly be applied to animals.

Literalists might tightly cling to the primary definitions, saying that murder refers only to humans, and that this is where the argument should end. But, as if anticipating this response, the Bible tells us, "He that killeth an ox is as if he slew a man." (Isaiah 66.3). Perhaps this suggests a closer link between "kill" and "murder."

A Broader Definition of "Murder"

Moreover, traditional biblical commentators viewed "murder" in a way that expands on the formal definitions of today, with subtle nuances infused with heartfelt compassion. In commenting on Exodus 20.13, early Jewish scholars write as follows: "Sages understood ‘bloodshed’ to include embarrassing a fellow human being in public so that the blood drains from his or her face, not providing safety for travelers, and causing anyone the loss of his or her livelihood. One may murder by the hand or with the tongue, by talebearing or by character assassination. One may murder by carelessness, by indifference . . ." Thus, rabbinical interpretation of the commandment includes more than just the literal taking of life. Worded another way, accepted Jewish definitions of murder stretch the envelope, as it were. It would not be unreasonable, then, to include the killing of animals – which necessitates the taking of life – under the general rubric of murder, for this would in some ways be less of a stretch than that traditionally found in standard Jewish definitions of the word.

But there is more. When Prabhupada refers to the "Thou shalt not kill" commandment, he generally refers to it as "the commandment of Jesus Christ," or he will preface it by saying, "Jesus says." This is quite telling. In fact, the New Testament reading of this commandment seeks to expand on its original definition: Luke (18.20), Mark (10.19), and Matthew (5.21) all exhort followers to go beyond conventional understandings of this command. To give but one example, let us look at Matthew: "You have heard that it was said to those in ancient times, ‘You shall not murder’; and ‘whoever murders shall be liable to judgment.’ But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment; and if you insult a brother or sister . . ."

In other words, we are no longer talking about "murder" but of inappropriate treatment. True, these statements address human interaction, first and foremost. But given biblical ideals about the original diet of man, which was vegetarian (see Genesis 1.29), and the ultimate vision of Isaiah (11.6-9) – that all creatures will one day live together in peace – it is clearly desirable that man begins to treat his co-inhabitors of the planet with dignity and respect. He can begin by not killing them.

Common-Sense Compassion

This is Prabhupada’s main point: In whatever way the original Jewish prophets and their modern representatives interpret the word "kill," a religions person should be able to invoke common sense and inborn human compassion – it is wrong to unnecessarily kill any living being. Prabhupada believes that a practicing religionist, especially, should have the good sense, character, and purity of purpose to know that taking life is not in our charge: We cannot create the life of an animal, and so we have no right to take it away. Prabhupada’s understanding of "Thou shalt not kill" is thus clearly legitimate – especially in light of the commandment’s restructuring as found in the New Testament. This is so because modern slaughterhouses go against the very spirit of the entire Judeo-Christian tradition – of religion in general – which seeks to abolish wrongful killing and to establish universal harmony and love throughout the creation.

* I found references and explanations for "Thou shalt not kill" in the Srimad-Bhagavatam; the Caitanya-caritamrta; Perfect Questions, Perfect Answers; The Science of Self-Realization; Life Comes From Life; Matchless Gifts; The Journey of Self-Discovery; The Quest for Enlightenment; Dialectical Spiritualism; and in countless lectures and Back to Godhead magazine articles. His other works, while not addressing the biblical command directly, certainly deal with related issues, and the commandment’s essence is not far in the background.

This article was adapted from the author’s book Holy Cow: The Hare Krishna Contribution to Vegetarianism and Animal Rights, just published by Lantern Books and available from the Krishna.com Store.

| Satyaraja Dasa (Steven J. Rosen) is an initiated disciple of His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. He is founding editor of the Journal of Vaishnava Studies and an associate editor of Back to Godhead Magazine. Rosen is also the author of numerous books, including the popular Gita on the Green: The Mystical Tradition Behind Bagger Vance (Continuum International, 2000) and The Hidden Glory of India (Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 2002). Several years ago he was called upon by Greenwood Press, a major academic publisher, to write the Hinduism volume for their “Introduction to the World’s Major Religions” series. | |

| The book did so well that they further commissioned him to write Essential Hinduism, a more comprehensive treatment of the same subject, under the auspices of their prestigious parent company (Praeger), and the book is now receiving worldwide acclaim. Rosen’s books have appeared in several languages, including Spanish, German, Hungarian, Czech, Swedish, Chinese, and Russian. His forthcoming work, Krishna’s Song: A New Look at the Bhagavad Gita (Greenwood, 2007), will explore key philosophical points in the Gita to illuminate the ancient text’s overall teaching and philosophical narrative. | |