The Deniable Darwin

By David Berlinski | May 07, 2010

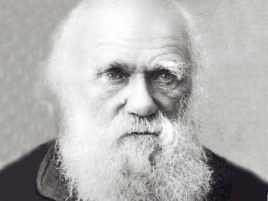

Charles Darwin presented On the Origin of Species to a disbelieving world in 1859 – three years after Clerk Maxwell had published “On Faraday’s Lines of Force,” the first of his papers on the electromagnetic field. Maxwell’s theory has by a process of absorption become part of quantum field theory, and so a part of the great canonical structure created by mathematical physics.

By contrast, the final triumph of Darwinian theory, although vividly imagined by biologists, remains, along with world peace and Esperanto, on the eschatological horizon of contemporary thought.

“It is just a matter of time,” one biologist wrote recently, reposing his faith in a receding hereafter, “before this fruitful concept comes to be accepted by the public as wholeheartedly as it has accepted the spherical earth and the sun-centered solar system.” Time, however, is what evolutionary biologists have long had, and if general acceptance has not come by now, it is hard to know when it ever will.

In its most familiar, textbook form, Darwin’s theory subordinates itself to a haunting and fantastic image, one in which life on earth is represented as a tree. So graphic has this image become that some biologists have persuaded themselves they can see the flowering tree standing on a dusty plain, the mammalian twig obliterating itself by anastomosis into a reptilian branch and so backward to the amphibia and then the fish, the sturdy chordate line – our line, cosa nostra – moving by slithering stages into the still more primitive trunk of life and so downward to the single irresistible cell that from within its folded chromosomes foretold the living future.

This is nonsense, of course. That densely reticulated tree, with its lavish foliage, is an intellectual construct, one expressing the hypothesis of descent with modification.

Evolution is a process, one stretching over four billion years. It has not been observed. The past has gone to where the past inevitably goes. The future has not arrived. The present reveals only the detritus of time and chance: the fossil record, and the comparative anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of different organisms and creatures. Like every other scientific theory, the theory of evolution lies at the end of an inferential trail.

The facts in favor of evolution are often held to be incontrovertible; prominent biologists shake their heads at the obduracy of those who would dispute them. Those facts, however, have been rather less forthcoming than evolutionary biologists might have hoped. If life progressed by an accumulation of small changes, as they say it has, the fossil record should reflect its flow, the dead stacked up in barely separated strata. But for well over 150 years, the dead have been remarkably diffident about confirming Darwin’s theory. Their bones lie suspended in the sands of time-theromorphs and therapsids and things that must have gibbered and then squeaked; but there are gaps in the graveyard, places where there should be intermediate forms but where there is nothing whatsoever instead.

Before the Cambrian era, a brief 600 million years ago, very little is inscribed in the fossil record; but then, signaled by what I imagine as a spectral puff of smoke and a deafening ta-da!, an astonishing number of novel biological structures come into creation, and they come into creation at once.

Thereafter, the major transitional sequences are incomplete. Important inferences begin auspiciously, but then trail off, the ancestral connection between Eusthenopteron and Ichthyostega, for example – the great hinge between the fish and the amphibia – turning on the interpretation of small grooves within Eusthenopteron’s intercalary bones. Most species enter the evolutionary order fully formed and then depart unchanged. Where there should be evolution, there is stasis instead – the term is used by the paleontologists Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge in developing their theory of “punctuated equilibria” – with the fire alarms of change going off suddenly during a long night in which nothing happens.

The fundamental core of Darwinian doctrine, the philosopher Daniel Dennett has buoyantly affirmed, “is no longer in dispute among scientists.” Such is the party line, useful on those occasions when biologists must present a single face to their public. But it was to the dead that Darwin pointed for confirmation of his theory; the fact that paleontology does not entirely support his doctrine has been a secret of long standing among paleontologists. “The known fossil record,” Steven Stanley observes, “fails to document a single example of phyletic evolution accomplishing a major morphologic transition and hence offers no evidence that the gradualistic model can be valid.”

Small wonder, then, that when the spotlight of publicity is dimmed, evolutionary biologists evince a feral streak, Stephen Jay Gould, Niles Eldredge, Richard Dawkins, and John Maynard Smith abusing one another roundly like wrestlers grappling in the dark.

Pause for the Logician

Swimming in the soundless sea, the shark has survived for millions of years, sleek as a knife blade and twice as dull. The shark is an organism wonderfully adapted to its environment. Pause. And then the bright brittle voice of logical folly intrudes: after all, it has survived for millions of years.

This exchange should be deeply embarrassing to evolutionary biologists. And yet, time and again, biologists do explain the survival of an organism by reference to its fitness and the fitness of an organism by reference to its survival, the friction between concepts kindling nothing more illuminating than the observation that some creatures have been around for a very long time. “Those individuals that have the most offspring,” writes Ernst Mayr, the distinguished zoologist, “are by definition . . . the fittest ones.” And in Evolution and the Myth of Creationism, Tim Berra states that “[f]itness in the Darwinian sense means reproductive fitness-leaving at least enough offspring to spread or sustain the species in nature.”

This is not a parody of evolutionary thinking; it is evolutionary thinking. Que sera, sera.

Evolutionary thought is suffused in general with an unwholesome glow. “The belief that an organ so perfect as the eye,” Darwin wrote, “could have been formed by natural selection is enough to stagger anyone.” It is. The problem is obvious. “What good,” Stephen Jay Gould asked dramatically, “is 5 percent of an eye?” He termed this question “excellent.”

The question, retorted the Oxford professor Richard Dawkins, the most prominent representative of ultra-Darwinians, “is not excellent at all”:

“Vision that is 5 percent as good as yours or mine is very much worth having in comparison with no vision at all. And 6 percent is better than 5, 7 percent better than 6, and so on up the gradual, continuous series.”

But Dawkins, replied Phillip Johnson in turn, had carelessly assumed that 5 percent of an eye would see 5 percent as well as an eye, and that is an assumption for which there is little evidence. (A professor of law at the University of California at Berkeley, Johnson has a gift for appealing to the evidence when his opponents invoke theory, and vice versa.)

Having been conducted for more than a century, exchanges of this sort may continue for centuries more; but the debate is an exercise in irrelevance. What is at work in sight is a visual system, one that involves not only the anatomical structures of the eye and forebrain, but the remarkably detailed and poorly understood algorithms required to make these structures work.

“When we examine the visual mechanism closely,” Karen K. de Valois remarked recently in Science, “although we understand much about its component parts, we fail to fathom the ways in which they fit together to produce the whole of our complex visual perception.”

These facts suggest a chastening reformulation of Gould’s “excellent” question, one adapted to reality: could a system we do not completely understand be constructed by means of a process we cannot completely specify?

The intellectually responsible answer to this question is that we do not know — we have no way of knowing. But that is not the answer evolutionary theorists accept. According to Daniel Dennett (in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea), Dawkins is “almost certainly right” to uphold the incremental view, because “Darwinism is basically on the right track.” In this, he echoes the philosopher Kim Sterenly, who is also persuaded that “something like Dawkins’s stories have got to be right” (emphasis added). After all, she asserts, “natural selection is the only possible explanation of complex adaptation.”

Dawkins himself has maintained that those who do not believe a complex biological structure may be constructed in small steps are expressing merely their own sense of “personal incredulity.” But in countering their animadversions he appeals to his own ability to believe almost anything. Commenting on the (very plausible) claim that spiders could not have acquired their web-spinning behavior by a Darwinian mechanism, Dawkins writes: “It is not impossible at all. That is what I firmly believe and I have some experience of spiders and their webs.” It is painful to see this advanced as an argument.

Unflagging Success

Darwin conceived of evolution in terms of small variations among organisms, variations which by a process of accretion allow one species to change continuously into another. This suggests a view in which living creatures are spread out smoothly over the great manifold of biological possibilities, like colors merging imperceptibly in a color chart.

Life, however, is absolutely nothing like this. Wherever one looks there is singularity, quirkiness, oddness, defiant individuality, and just plain weirdness. The male redback spider (Latrodectus hasselti), for example, is often consumed during copulation. Such is sexual cannibalism — the result, biologists have long assumed, of “predatory females overcoming the defenses of weaker males.” But it now appears that among Latrodectus basselti, the male is complicit in his own consumption. Having achieved intromission, this schnook performs a characteristic somersault, placing his abdomen directly over his partner’s mouth. Such is sexual suicide-awfulness taken to a higher power.

It might seem that sexual suicide confers no advantage on the spider, the male passing from ecstasy to extinction in the course of one and the same act. But spiders willing to pay for love are apparently favored by female spiders (no surprise, there); and female spiders with whom they mate, entomologists claim, are less likely to mate again. The male spider perishes; his preposterous line persists.

This explanation resolves one question only at the cost of inviting another: why such bizarre behavior? In no other Latrodectus species does the male perform that obliging somersault, offering his partner the oblation of his life as well as his love. Are there general principles that specify sexual suicide among this species, but that forbid sexual suicide elsewhere? If so, what are they?

Once asked, such questions tend to multiply like party guests. If evolutionary theory cannot answer them, what, then, is its use? Why is the Pitcher plant carnivorous, but not the thorn bush, and why does the Pacific salmon require fresh water to spawn, but not the Chilean sea bass? Why has the British thrush learned to hammer snails upon rocks, but not the British blackbird, which often starves to death in the midst of plenty? Why did the firefly discover bioluminescence, but not the wasp or the warrior ant; why do the bees do their dance, but not the spider or the flies; and why are women, but not cats, born without the sleek tails that would make them even more alluring than they already are?

Why? Yes, why? The question, simple, clear, intellectually respectable, was put to the Nobel laureate George Wald. “Various organisms try various things,” he finally answered, his words functioning as a verbal shrug, “they keep what works and discard the rest.”

But suppose the manifold of life were to be given a good solid yank, so that the Chilean sea bass but not the Pacific salmon required fresh water to spawn, or that ants but not fireflies flickered enticingly at twilight, or that women but not cats were born with lush tails. What then? An inversion of life’s fundamental facts would, I suspect, present evolutionary biologists with few difficulties. Various organisms try various things. This idea is adapted to any contingency whatsoever, an interesting example of a Darwinian mechanism in the development of Darwinian thought itself.

A comparison with geology is instructive. No geological theory makes it possible to specify precisely a particular mountain’s shape; but the underlying process of upthrust and crumbling is well understood, and geologists can specify something like a mountain’s generic shape. This provides geological theory with a firm connection to reality. A mountain arranging itself in the shape of the letter “A” is not a physically possible object; it is excluded by geological theory.

The theory of evolution, by contrast, is incapable of ruling anything out of court. That job must be done by nature. But a theory that can confront any contingency with unflagging success cannot be falsified. Its control of the facts is an illusion.

Sheer Dumb Luck

Chance alone,” the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Jacques Monod once wrote, “is at the source of every innovation, of all creation in the biosphere. Pure chance, absolutely free but blind, is at the very root of the stupendous edifice of creation.”

The sentiment expressed by these words has come to vex evolutionary biologists. “This belief,” Richard Dawkins writes, “that Darwinian evolution is ‘random,’ is not merely false. It is the exact opposite of the truth.” But Monod is right and Dawkins wrong. Chance lies at the beating heart of evolutionary theory, just as it lies at the beating heart of thermodynamics.

It is the second law of thermodynamics that holds dominion over the temporal organization of the universe, and what the law has to say we find verified by ordinary experience at every turn. Things fall apart. Energy, like talent, tends to squander itself. Liquids go from hot to lukewarm. And so does love. Disorder and despair overwhelm the human enterprise, filling our rooms and our lives with clutter. Decay is unyielding. Things go from bad to worse. And overall, they go only from bad to worse.

These grim certainties the second law abbreviates in the solemn and awful declaration that the entropy of the universe is tending toward a maximum. The final state in which entropy is maximized is simply more likely than any other state. The disintegration of my face reflects nothing more compelling than the odds. Sheer dumb luck.

But if things fall apart, they also come together. Life appears to offer at least a temporary rebuke to the second law of thermodynamics. Although biologists are unanimous in arguing that evolution has no goal, fixed from the first, it remains true nonetheless that living creatures have organized themselves into ever more elaborate and flexible structures. If their complexity is increasing, the entropy that surrounds them is decreasing. Whatever the universe-as-a-whole may be doing — time fusing incomprehensibly with space, the great stars exploding indignantly — biologically things have gone from bad to better, the show organized, or so it would seem, as a counterexample to the prevailing winds of fate.

How so? The question has historically been the pivot on which the assumption of religious belief has turned. How so? “God said: ‘Let the waters swarm with swarms of living creatures, and let fowl fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven.”‘ That is how so. And who on the basis of experience would be inclined to disagree? The structures of life are complex, and complex structures get made in this, the purely human world, only by a process of deliberate design. An act of intelligence is required to bring even a thimble into being; why should the artifacts of life be different?

Darwin’s theory of evolution rejects this counsel of experience and intuition. Instead, the theory forges, at least in spirit, a perverse connection with the second law itself, arguing that precisely the same force that explains one turn of the cosmic wheel explains another: sheer dumb luck.

If the universe is for reasons of sheer dumb luck committed ultimately to a state of cosmic listlessness, it is also by sheer dumb luck that life first emerged on earth, the chemicals in the pre-biotic seas or soup illuminated and then invigorated by a fateful flash of lightning. It is again by sheer dumb luck that the first self-reproducing systems were created. The dense and ropy chains of RNA — they were created by sheer dumb luck, and sheer dumb luck drove the primitive chemicals of life to form a living cell. It is sheer dumb luck that alters the genetic message so that, from infernal nonsense, meaning for a moment emerges; and sheer dumb luck again that endows life with its opportunities, the space of possibilities over which natural selection plays, sheer dumb luck creating the mammalian eye and the marsupial pouch, sheer dumb luck again endowing the elephant’s sensitive nose with nerves and the orchid’s translucent petal with blush.

Amazing. Sheer dumb luck.

Life, Complex Life

Physicists are persuaded that things are in the end simple; biologists that they are not. A good deal depends on where one looks. Wherever the biologist looks, there is complexity beyond complexity, the entanglement of things ramifying downward from the organism to the cell. In a superbly elaborated figure, the Australian biologist Michael Denton compares a single cell to an immense automated factory, one the size of a large city:

On the surface of the cell we would see millions of openings, like the portholes of a vast space ship, opening and closing to allow a continual stream of materials to flow in and out. If we were to enter one of these openings we would find ourselves in a world of supreme technology and bewildering complexity. We would see endless highly organized corridors and conduits branching in every direction away from the perimeter of the cell, some leading to the central memory bank in the nucleus and others to assembly plants and processing units. The nucleus itself would be a vast spherical chamber more than a kilometer in diameter, resembling a geodesic dome inside of which we would see, all neatly stacked together in ordered arrays, the miles of coiled chains of the DNA molecule…. We would notice that the simplest of the functional components of the cell, the protein molecules, were, astonishingly, complex pieces of molecular machinery….Yet the life of the cell depends on the integrated activities of thousands, certainly tens, and probably hundreds of thousands of different protein molecules.

And whatever the complexity of the cell, it is insignificant in comparison with the mammalian nervous system; and beyond that, far impossibly ahead, there is the human mind, an instrument like no other in the biological world, conscious, flexible, penetrating, inscrutable, and profound.

It is here that the door of doubt begins to swing. Chance and complexity are countervailing forces; they work at cross-purposes. This circumstance the English theologian William Paley (1743-1805) made the gravamen of his well-known argument from design:

Nor would any man in his senses think the existence of the watch, with its various machinery, accounted for, by being told that it was one out of possible combinations of material forms; that whatever he had found in the place where he found the watch, must have contained some internal configuration or other, and that this configuration might be the structure now exhibited, viz., of the works of a watch, as well as a different structure. It is worth remarking, it is simply a fact, that this courtly and old-fashioned argument is entirely compelling. We never attribute the existence of a complex artifact to chance. And for obvious reasons: complex objects are useful islands, isolated amid an archipelago of useless possibilities. Of the thousands of ways in which a watch might be assembled from its constituents, only one is liable to work. It is unreasonable to attribute the existence of a watch to chance, if only because it is unlikely. An artifact is the overflow in matter of the mental motions of intention, deliberate design, planning, and coordination. The inferential spool runs backward, and it runs irresistibly from a complex object to the contrived, the artificial, circumstances that brought it into being.

Paley allowed the conclusion of his argument to drift from man-made to biological artifacts, a human eye or kidney falling under the same classification as a watch. “Every indication of contrivance,” he wrote, “every manifestation of design, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation.

In this drifting, Darwinists see dangerous signs of a non sequitur. There is a tight connection, they acknowledge, between what a watch is and how it is made; but the connection unravels at the human eye — or any other organ, disposition, body plan, or strategy — if only because another and a simpler explanation is available. Among living creatures, say Darwinists, the design persists even as the designer disappears.

“Paley’s argument,” Dawkins writes, “is made with passionate sincerity and is informed by the best biological scholarship of his day, but it is wrong, gloriously and utterly wrong.”

The enormous confidence this quotation expresses must be juxtaposed against the weight of intuition it displaces. It is true that intuition is often wrong-quantum theory is intuition’s graveyard. But quantum theory is remote from experience; our intuitions in biology lie closer to the bone. We are ourselves such stuff as genes are made on, and while this does not establish that our assessments of time and chance must be correct, it does suggest that they may be pertinent.

The Book of Life

The Discovery of DNA by James D. Watson and Francis Crick in 1952 revealed that a living creature is an organization of matter orchestrated by a genetic text. Within the bacterial cell, for example, the book of life is written in a distinctive language. The book is read aloud, its message specifying the construction of the cell’s constituents, and then the book is copied, passed faithfully into the future.

This striking metaphor introduces a troubling instability, a kind of tremor, into biological thought. With the discovery of the genetic code, every living creature comes to divide itself into alien realms: the alphabetic and the organismic. The realms are conceptually distinct, responding to entirely different imperatives and constraints. An alphabet, on the one hand, belongs to the class of finite combinatorial objects, things that are discrete and that fit together in highly circumscribed ways. An organism, on the other hand, traces a continuous figure in space and in time. How, then, are these realms coordinated?

I ask the question because in similar systems, coordination is crucial. When I use the English language, the rules of grammar act as a constraint on the changes that I might make to the letters or sounds I employ. This is something we take for granted, an ordinary miracle in which I pass from one sentence to the next, almost as if crossing an abyss by means of a series of well-placed stepping stones.

In living creatures, things evidently proceed otherwise. There is no obvious coordination between alphabet and organism; the two objects are governed by different conceptual regimes, and that apparently is the end of it. Under the pressures of competition, the orchid Orphrys apifera undergoes a statistically adapted drift, some incidental feature in its design becoming over time ever more refined, until, consumed with longing, a misguided bee amorously mounts the orchid’s very petals, convinced that he has seen shimmering there a female’s fragile genitalia. As this is taking place, the marvelous mimetic design maturing slowly, the orchid’s underlying alphabetic system undergoes a series of random perturbations, letters in its genetic alphabet winking off or winking on in a way utterly independent of the grand convergent progression toward perfection taking place out there where the action is.

We do not understand, we cannot re-create, a system of this sort. However it may operate in life, randomness in language is the enemy of order, a way of annihilating meaning And not only in language, but in any language-like system — computer programs, for example. The alien influence of randomness in such systems was first noted by the distinguished French mathematician M.P. Schutzenberger, who also marked the significance of this circumstance for evolutionary theory. “If we try to simulate such a situation,” he wrote, “by making changes randomly . . . on computer programs, we find that we have no chance . . . even to see what the modified program would compute; it just jams.

Planets of Possibility

This is not yet an argument, only an expression of intellectual unease; but the unease tends to build as analogies are amplified. The general issue is one of size and space, and the way in which something small may be found amidst something very big.

Linguists in the 1950’s, most notably Noam Chomsky and George Miller, asked dramatically how many grammatical English sentences could be constructed with 100 letters. Approximately 10 to the 25th power, they answered. This is a very large number. But a sentence is one thing; a sequence, another. A sentence obeys the laws of English grammar; a sequence is lawless and comprises any concatenation of those 100 letters. If there are roughly (1025) sentences at hand, the number of sequences 100 letters in length is, by way of contrast, 26 to the 100th power. This is an inconceivably greater number. The space of possibilities has blown up, the explosive process being one of combinatorial inflation.

Now, the vast majority of sequences drawn on a finite alphabet fail to make a statement: they consist of letters arranged to no point or purpose. It is the contrast between sentences and sequences that carries the full, critical weight of memory and intuition. Organized as a writhing ball, the sequences resemble a planet-sized object, one as large as pale Pluto. Landing almost anywhere on that planet, linguists see nothing but nonsense. Meaning resides with the grammatical sequences, but they, those sentences, occupy an area no larger than a dime.

How on earth could the sentences be discovered by chance amid such an infernal and hyperborean immensity of gibberish? They cannot be discovered by chance, and, of course, chance plays no role in their discovery. The linguist or the native English-speaker moves around the place or planet with a perfectly secure sense of where he should go, and what he is apt to see.

The eerie and unexpected presence of an alphabet in every living creature might suggest the possibility of a similar argument in biology. It is DNA of course, that acts as life’s primordial text, the code itself organized in nucleic triplets, like messages in Morse code. Each triplet is matched to a particular chemical object, an amino acid. There are twenty such acids in all. They correspond to letters in an alphabet. As the code is read somewhere in life’s hidden housing, the linear order of the nucleic acids induces a corresponding linear order in the amino acids. The biological finger writes, and what the cell reads is an ordered presentation of such amino acids-a protein.

Like the nucleic acids, proteins are alphabetic objects, composed of discrete constituents. On average, proteins are roughly 250 amino acid residues in length, so a given protein may be imagined as a long biochemical word, one of many.

The aspects of an analogy are now in place. What is needed is a relevant contrast, something comparable to sentences and sequences in language. Of course nothing completely comparable is at hand: there are no sentences in molecular biology. Nonetheless, there is this fact, helpfully recounted by Richard Dawkins: “The actual animals that have ever lived on earth are a tiny subset of the theoretical animals that could exist.” It follows that over the course of four billion years, life has expressed itself by means of a particular stock of proteins, a certain set of life-like words.

A combinatorial count is now possible. The MIT physicist Murray Eden, to whom I owe this argument, estimates the number of the viable proteins at 10 to the 50th power. Within this set is the raw material of everything that has ever lived: the flowering plants and the alien insects and the seagoing turtles and the sad shambling dinosaurs, the great evolutionary successes and the great evolutionary failures as well. These creatures are, quite literally, composed of the proteins that over the course of time have performed some useful function, with “usefulness” now standing for the sense of sentencehood in linguistics.

As in the case of language, what has once lived occupies some corner in the space of a larger array of possibilities, the actual residing in the shadow of the possible. The space of all possible proteins of a fixed length (250 residues, recall) is computed by multiplying 20 by itself 250 times (20 to the 250th power). It is idle to carry out the calculation. The numbers larger by far than seconds in the history of the world since the Big Bang or grains of sand on the shores of every sounding sea. Another planet now looms in the night sky, Pluto-sized or bigger, a conceptual companion to the planet containing every sequence composed by endlessly arranging the 26 English letters into sequences 100 letters in length. This planetary doppelganger is the planet of all possible proteins of fixed length, the planet, in a certain sense, of every conceivable form of carbon-based life.

And there the two planets lie, spinning on their soundless axes. The contrast between sentences and sequences on Pluto reappears on Pluto’s double as the contrast between useful protein forms and all the rest; and it reappears in terms of the same dramatic difference in numbers, the enormous (20 to the 25th power) overawing the merely big (10 to the 50th power), the contrast between the two being quite literally between an immense and swollen planet and a dime’s worth of area. That dime-sized corner, which on Pluto contains the English sentences, on Pluto’s double contains the living creatures; and there the biologist may be seen tramping, the warm puddle of wet life achingly distinct amid the planet’s snow and stray proteins. It is here that living creatures, whatever their ultimate fate, breathed and moaned and carried on, life evidently having discovered the small quiet corner of the space of possibilities in which things work.

It would seem that evolution, Murray Eden writes in artfully ambiguous language, “was directed toward the incredibly small proportion of useful protein forms. . . ,” the word “directed” conveying, at least to me, the sobering image of a stage-managed search, with evolution bypassing the awful immensity of all that frozen space because in some sense evolution knew where it was going.

And yet, from the perspective of Darwinian theory, it is chance that plays the crucial — that plays the only role in generating the proteins. Wandering the surface of a planet, evolution wanders blindly, having forgotten where it has been, unsure of where it is going.

The Artificer of Design

Random mutations are the great creative demiurge of evolution, throwing up possibilities and bathing life in the bright light of chance. Each living creature is not only what it is but what it might be. What, then, acts to make the possible palpable?

The theory of evolution is a materialistic theory. Various deities need not apply. Any form of mind is out. Yet a force is needed, something adequate to the manifest complexity of the biological world, and something that in the largest arena of all might substitute for the acts of design, anticipation, and memory that are obvious features of such day-to-day activities as fashioning a sentence or a sonnet.

This need is met in evolutionary theory by natural selection, the filter but not the source of change. “It may be said,” Darwin wrote,

that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinizing, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good: silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, as the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life.

Natural selection emerges from these reflections as a strange force-like concept. It is strange because it is unconnected to any notion of force in physics, and it is force-like because natural selection does something, it has an effect and so unctions as a kind of cause.

Creatures, habits, organ systems, body plans, organs, and tissues are shaped by natural selection. Population geneticists write of selection forces, selection pressures, and coefficients of natural selection; biologists say that natural selection sculpts, shapes, coordinates, transforms, directs, controls, changes, and transfigures living creatures.

It is natural selection, Richard Dawkins believes, that is the artificer of design, a cunning force that mocks human ingenuity even as it mimics it:

Charles Darwin showed how it is possible for blind physical forces to mimic the effects of conscious design, and, by operating as a cumulative filter of chance variations, to lead eventually to organized and adaptive complexity, to mosquitoes and mammoths, to humans and therefore, indirectly, to books and computers.

In affirming what Darwin showed, these words suggest that Darwin demonstrated the power of natural selection in some formal sense, settling the issue once and for all. But that is simply not true. When Darwin wrote, the mechanism of evolution that he proposed had only life itself to commend it. But to refer to the power of natural selection by appealing to the course of evolution is a little like confirming a story in the New York Times by reading it twice. The theory of evolution is, after all, a general theory of change; if natural selection can sift the debris of chance to fashion an elephant’s trunk, should it not be able to work elsewhere- amid computer programs and algorithms, words and sentences? Skeptics require a demonstration of natural selection’s cunning, one that does not involve the very phenomenon it is meant to explain.

No sooner said than done. An extensive literature is now devoted to what is optimistically called artificial life. These are schemes in which a variety of programs generate amusing computer objects and by a process said to be similar to evolution show that they are capable of growth and decay and even a phosphorescent simulacrum of death. An algorithm called “Face Prints,” for example, has been designed to enable crime victims to identify their attackers. The algorithm runs through hundreds of facial combinations (long hair, short hair, big nose, wide chin, moles, warts, wens, wrinkles) until the indignant victim spots the resemblance between the long-haired, big-nosed, widechinned portrait of the perpetrator and the perpetrator himself.

It is the presence of the human victim in this scenario that should give pause. What is be doing there, complaining loudly amid those otherwise blind forces? A mechanism that requires a discerning human agent cannot be Darwinian. The Darwinian mechanism neither anticipates nor remembers. It gives no directions and makes no choices. What is unacceptable in evolutionary theory, what is strictly forbidden, is the appearance of a force with the power to survey time, a force that conserves a point or a property because it will be useful. Such a force is no longer Darwinian. How would a blind force know such a thing? And by what means could future usefulness be transmitted to the present?

If life is, as evolutionary biologists so often say, a matter merely of blind thrusting and throbbing, any definition of natural selection must plainly meet what I have elsewhere called a rule against deferred success.

It is a rule that cannot be violated with impunity; if evolutionary theory is to retain its intellectual integrity, it cannot be violated at all.

But the rule is widely violated, the violations so frequent as to amount to a formal fallacy.

Advent of the Head Monkey

It is Richard Dawkins’s grand intention in The Blind Watchmaker to demonstrate, as one reviewer enthusiastically remarked, “how natural selection allows biologists to dispense with such notions as purpose and design.” This he does by exhibiting a process in which the random exploration of certain possibilities, a blind stab here, another there, is followed by the filtering effects of natural selection, some of those stabs saved, others discarded. But could a process so conceived — a Darwinian process — discover a simple English sentence: a target, say, chosen from Shakespeare? The question is by no means academic. If natural selection cannot discern a simple English sentence, what chance is there that it might have discovered the mammalian eye or the system by which glucose is regulated by the liver? A thought experiment in The Blind Watchmaker now follows. Randomness in the experiment is conveyed by the metaphor of the monkeys, perennial favorites in the theory of probability. There they sit, simian hands curved over the keyboards of a thousand typewriters, their long agile fingers striking keys at random. It is an image of some poignancy, those otherwise intelligent apes banging away at a machine they cannot fathom; and what makes the poignancy pointed is the fact that the system of rewards by which the apes have been induced to strike the typewriter’s keys is from the first rigged against them.

The probability that a monkey will strike a given letter is one in 26. The typewriter has 26 keys: the monkey, one working finger. But a letter is not a word. Should Dawkins demand that the monkey get two English letters right, the odds against success rise with terrible inexorability from one in 26 to one in 676. The Shakespearean target chosen by Dawkins — “Methinks it is like a weasel”-is a six-word sentence containing 28 English letters (including the spaces). It occupies an isolated point in a space of 10,000 million, million, million, million, million, million possibilities. This is a very large number; combinatorial inflation is at work. And these are very long odds. And a six-word sentence consisting of 28 English letters is a very short, very simple English sentence.

Such are the fatal facts. The problem confronting the monkeys is, of course, a double one: they must, to be sure, find the right letters, but they cannot lose the right letters once they have found them. A random search in a space of this size is an exercise in irrelevance. This is something the monkeys appear to know. What more, then, is expected; what more required? Cumulative selection, Dawkins argues- the answer offered as well by Stephen Jay Gould, Manfred Eigen, and Daniel Dennett. The experiment now proceeds in stages. The monkeys type randomly. After a time, they are allowed to survey what they have typed in order to choose the result “which however slightly most resembles the target phrase.” It is a computer that in Dawkins’s experiment performs the crucial assessments, but I prefer to imagine its role assigned to a scrutinizing monkey-the Head Monkey of the experiment. The process under way is one in which stray successes are spotted and then saved. This process is iterated and iterated again. Variations close to the target are conserved because they are close to the target, the Head Monkey equably surveying the scene until, with the appearance of a miracle in progress, randomly derived sentences do begin to converge on the target sentence itself.

The contrast between schemes and scenarios is striking. Acting on their own, the monkeys are adrift in fathomless possibilities, any accidental success-a pair of English-like letters-lost at once, those successes seeming like faint untraceable lights flickering over a wine-dark sea. The advent of the Head Monkey changes things entirely. Successes are conserved and then conserved again. The light that formerly flickered uncertainly now stays lit, a beacon burning steadily, a point of illumination. By the light of that light, other lights are lit, until the isolated successes converge, bringing order out of nothingness.

The entire exercise is, however, an achievement in self-deception. A target phrase? Iterations that most resemble the target? A Head Monkey that measures the distance between failure and success? If things are sightless, how is the target represented, and how is the distance between randomly generated phrases and the targets assessed? And by whom? And the Head Monkey? What of him? The mechanism of deliberate design, purged by Darwinian theory on the level of the organism, has reappeared in the description of natural selection itself, a vivid example of what Freud meant by the return of the repressed.

This is a point that Dawkins accepts without quite acknowledging, rather like a man adroitly separating his doctor’s diagnosis from his own disease.

Nature presents life with no targets. Life shambles forward, surging here, shuffling there, the small advantages accumulating on their own until something novel appears on the broad evolutionary screen-an arch or an eye, an intricate pattern of behavior, the complexity characteristic of life. May we, then, see this process at work, by seeing it simulated?

“Unfortunately,” Dawkins writes, “I think it may be beyond my powers as a programmer to set up such a counterfeit world.”7

This is the authentic voice of contemporary Darwinian theory. What may be illustrated by the theory does not involve a Darwinian mechanism; what involves a Darwinian mechanism cannot be illustrated by the theory.

Darwin Without Darwinism

Biologists oftenaffirm that as members of the scientific community they positively welcome criticism. Nonsense. Like everyone else, biologists loathe criticism and arrange their lives so as to avoid it. Criticism has nonetheless seeped into their souls, the process of doubt a curiously Darwinian one in which individual biologists entertain minor reservations about their theory without ever recognizing the degree to which these doubts mount up to a substantial deficit. Creationism, so often the target of their indignation, is the least of their worries.

For many years, biologists have succeeded in keeping skepticism on the circumference of evolutionary thought, where paleontologists, taxonomists, and philosophers linger. But the burning fringe of criticism is now contracting, coming ever closer to the heart of Darwin’s doctrine. In a paper of historic importance, Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin expressed their dissatisfaction with what they termed “just-so” stories in biology.

It is by means of a just-so story, for example, that the pop biologist Elaine Morgan explains the presence in human beings of an aquatic diving reflex. An obscure primate ancestral to man, Morgan argues, was actually aquatic, having returned to the sea like the dolphin. Some time later, that primate, having tired of the water, clambered back to land, his aquatic adaptations intact. Just so.

If stories of this sort are intellectually inadequate — preposterous, in fact — some biologists are prepared to argue that they are unnecessary as well, another matter entirely. “How seriously,” H. Allen Orr asked in a superb if savage review of Dennett’s Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, should we take these endless adaptive explanations of features whose alleged Design may be illusory? Isn’t there a difference between those cases where we recognize Design before we understand its precise significance and those cases where we try to make Design manifest concocting a story? And isn’t it especially worrisome that we can make up arbitrary traits faster than adaptive stories, and adaptive stories faster than experimental tests?

The camel’s lowly hump and the elephant’s nose — these, Orr suggests, may well be adaptive and so designed by natural selection. But beyond the old familiar cases, life may not be designed at all, the weight of evolution borne by neutral mutations, with genes undergoing a slow but pointless drifting in time’s soft currents.

Like Orr, many biologists see an acknowledgment of their doubts as a cagey, a calculated, concession; but cagey or not, it is a concession devastating to the larger project of Darwinian biology. Unable to say what evolution has accomplished, biologists now find themselves unable to say whether evolution has accomplished it. This leaves evolutionary theory in the doubly damned position of having compromised the concepts needed to make sense of life — complexity, adaptation, design – while simultaneously conceding that the theory does little to explain them.

No doubt, the theory of evolution will continue to play the singular role in the life of our secular culture that it has always played. The theory is unique among scientific instruments in being cherished not for what it contains, but for what it lacks. There are in Darwin’s scheme no biotic laws, no Bauplan as in German natural philosophy, no special creation, no elan vital, no divine guidance or transcendental forces. The theory functions simply as a description of matter in one of its modes, and living creatures are said to be something that the gods of law indifferently sanction and allow.

“Darwin,” Richard Dawkins has remarked with evident gratitude, “made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist.” This is an exaggeration, of course, but one containing a portion of the truth. That Darwin’s theory of evolution and biblical accounts of creation play similar roles in the human economy of belief is an irony appreciated by altogether too few biologists.

On the Derivation of Ulysses from Don Quixote

I imagine this story being told to me by Jorge Luis Borges one evening in a Buenos Aires cafe.

His voice dry and infinitely ironic, the aging, nearly blind literary master observes that “the Ulysses,” mistakenly attributed to the Irishman James Joyce, is in fact derived from “the Quixote.”

I raise my eyebrows.

Borges pauses to sip discreetly at the bitter coffee our waiter has placed in front of him, guiding his hands to the saucer.

“The details of the remarkable series of events in question may be found at the University of Leiden,” he says. “They were conveyed to me by the Freemason Alejandro Ferri in Montevideo.”

Borges wipes his thin lips with a linen handkerchief that he has withdrawn from his breast pocket.

“As you know,” he continues, “the original handwritten text of the Quixote was given to an order of French Cistercians in the autumn of 1576.”

I hold up my hand to signify to our waiter that no further service is needed.

“Curiously enough, for none of the brothers could read Spanish, the Order was charged by the Papal Nuncio, Hoyo dos Monterrey (a man of great refinement and implacable will), with the responsibility for copying the Quixote, the printing press having then gained no currency in the wilderness of what is now known as the department of Auvergne. Unable to speak or read Spanish, a language they not unreasonably detested, the brothers copied the Quixote over and over again, re-creating the text but, of course, compromising it as well, and so inadvertently discovering the true nature of authorship. Thus they created Fernando Lor’s Los Hombres d’Estado in 1585 by means of a singular series of copying errors, and then in 1654 Juan Luis Samorza’s remarkable epistolary novel Por Favor by the same means, and then in 1685, the errors having accumulated sufficiently to change Spanish into French, Moliere’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, their copying continuous and indefatigable, the work handed down from generation to generation as a sacred but secret trust, so that in time the brothers of the monastery, known only to members of the Bourbon house and, rumor has it, the Englishman and psychic Conan Doyle, copied into creation Stendhal’s The Red and the Black and Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and then as a result of a particularly significant series of errors, in which French changed into Russian, Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Anna Karenina. Late in the last decade of the 19th century there suddenly emerged, in English, Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, and then the brothers, their numbers reduced by an infectious disease of mysterious origin, finally copied the Ulysses into creation in 1902, the manuscript lying neglected for almost thirteen years and then mysteriously making its way to Paris in 1915, just months before the British attack on the Somme, a circumstance whose significance remains to be determined.”

I sit there, amazed at what Borges has recounted. “Is it your understanding, then,” I ask, “that every novel in the West was created in this way?”

“Of course,” replies Borges imperturbably. Then he adds: “Although every novel is derived directly from another novel, there is really only one novel, the Quixote.”