The Gita on Skid Row

By Sam Slovick | Nov 18, 2007

The yogis should perform acts for the advancement of human society. There are many purificatory processes for advancing a human being to spiritual life. The Lord says here that any sacrifice which is meant for human welfare should never be given up”¦. All prescribed sacrifices are meant for achieving the Supreme Lord. Therefore, in the lower stages, they should not be given up. Similarly, charity is for the purification of the heart. If charity is given to suitable persons, as described previously, it leads one to advanced spiritual life.” — His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

Downtown Los Angeles is pristine after a day of rain. The buildings in the historic corridor, pregnant with moisture, are dense with color. The usual garbage-strewn, urine-drenched streets have been washed clean. With the air now clear, the skyscrapers in the financial district, the symbols of money and power, are gleaming in the morning sun. It seems like you could get a good burn from the reflected light on the sidewalk a few blocks away from the procession of homeless despair on skid row.

This is when skid row is saddest. When it’s clean. The people who live exposed to the elements have vanished to the shelters and the missions, or stuck it out in their tents and cardboard boxes for the night; the streets now purified and cleansed only accentuate the human misery. The clouds cleared, San Julian between 6th and 7th is the scene of a different kind of gathering storm. It’s a deluge of despair.

The dealers, the junkies, the parade of disenfranchised collect like raindrops on a windshield. It’s all happening in the street, in plain view through the window of my car. Like a zoo. A human zoo.

Things look very different when you get out of the car and walk the streets. This zoo is a community. Everybody knows each other. I know a lot of them after living here on skid row for a couple of years. The scary scene reveals itself to be people who have fallen through the cracks all the way to the bottom, now struggling to get up.

The festering wound of Central City East blazes in the reflected glare of monuments to Maya; the five-star hotels just a few blocks from ‘little Calcutta.’ What’s distinctive about the skid row in Los Angeles is the scope of it with so much money and so much suffering so close to each other, the proximity of Central City; the heart chakra of Hollywood to the galleries, clubs, the restaurants and shops. You can spit from the window of a $1,500 a night suite at the New Otani Hotel on 2nd and Los Angeles streets, and it will land on people sleeping on the street below. LAPD Police Chief Bratton calls it, “The worst social disaster in America.”

It’s a mirror image of our societies’ insides. We are not doing so well for the widows, the orphans and the strangers in the land here in tinsel town adjacent. Skid row represents 50 square blocks of prime real estate that’s home to 9,000 people in varied states of homelessness: sleeping on the concrete, taking shelter in SRO (single room occupancy) hotels, others in the privately funded mega Missions, other transitional housing, and in cardboard boxes and tents. In fact, as a society, we’re failing catastrophically.

Wendy is camped out on the sidewalk of 6th and San Pedro. She’s a large black woman in a black dress that doubles as a nightgown, the shiny paint on her few remaining extra-long, glamour length artificial nails is chipping away like the last vestiges of her dignity. She’s adorned with big gold hoop earrings and frizzy hair with two-inch dark roots that indicate it hasn’t been tended to for a while. Her home is made up of a small tent and a few pieces of corrugated cardboard that form a makeshift structure, filled with some blankets and a few belongings in a suitcase. “I’m going to sue the city for a hundred million dollars,” she says. She is intelligent and articulate, with great social skills. She could be a CEO’s assistant, or running a business of her own. “I’m gonna sue Villaragosa for a hundred million dollars,” she says again over the sound of a five-piece church band on the other side of the concrete wall. It’s Sunday and Wendy’s squat is outside the building that houses the Church of the Nazarene.

Wendy continues a practiced rant about the mayor’s Safer Cities Initiative; a multi-agency program to reduce crime and the culture of lawlessness and address the issues plaguing Central City for decades. The initiative that has earmarked one hundred million dollars over an extended period of time has skid row looking a lot cleaner these days and has displaced homeless people wandering to other nearby areas like Boyle Heights, under the 4th and 6th street bridges, over toward Elysian Park.

The thing that has occurred to me after living here and getting to know the people living on the streets is that everyone in the geography, like Wendy, is in an accelerated transformation. It takes on many forms. Sometimes from dark to light, like an old man named Spanky who lived on the street, shooting dope for 38 years and then one day moved into the Midnight Mission and changed his life. Sometimes the change takes on other forms”¦even death. Always at a hyper-accelerated pace. It’s a vortex.

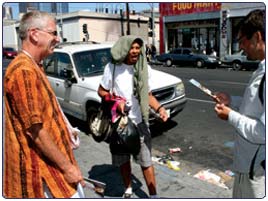

I round the corner onto 6th street across from the Midnight Mission as two Hare Krishna devotees draped in ochre robes approach Wendy with pamphlets and smiles. Nrsimhananda, an old-school devotee in the upper echelons of the Los Angeles hierarchy is accompanied by a 27-year-old Brazilian devotee named Uddavaha Gita. Both have their Bhakti yoga bases covered through their activities in ITV Productions, Inc. (ISKCON Television) which independently manages, produces and distributes ISKCON DVDs and videos including archives of footage of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

Uddavaha and Nirshimyanada are not novices in the realm of philanthropy. Devotional service is central to the lives of devotees and the two have a wide range of Vedic references to draw on. Uddavaha is from Rio, so squalor and poverty are not new to him: Rio’s Rocinha is home to the biggest slum on the planet. Still, we’re in the first world here in L.A”¦.aren’t we?

Wendy’s up and talking. She wants to hear all about what the devotees have to say before doing a sort of impromptu craniosacral blessing on one of them, holding his head in her hands and praying.

There’s no shortage of God on the row. Around the corner on 6th Street there are lines leading to makeshift stages with preachers and bands praising Jesus and serving up breakfast burritos. On 5th and Crocker, an aging priest, Father Maurice Chase (like the bank), is standing on the corner with a stack of bills, handing out singles and blessings to a line of homeless people wound down the trash-strewn street. There are Buddhist temples and churches all over the 50 square blocks of skid row. With the relentless labyrinth of worship and suffering comes philanthropy. It’s as wide-ranging and multilayered as this complicated area. Philanthropy is a mainstay in this world of trans-generational cyclical poverty. It’s a fixture in this area that’s home to the darker side of capitalism in the land of much and then some. I was aware of that and expected it as part of the lay of the land.

The thing that overwhelmed and outraged me was the kids on display. They’re here for the centralized services, they wait for little yellow school busses to pick them up outside the missions in the squalor. They were all over the Row, living in the missions and the welfare hotels side-by-side with the disproportionally large number of registered sex offenders in the area.

I wanted to do something. Who wouldn’t? Seeing the kids caused me to undergo a series of internal contortions where I tried to wrap my heart around what I believed about philanthropy: that it’s a feel-good endeavor for the doer. It may sometimes be a very profitable feel-good endeavor but not so good for the recipient. I was all judgment with regard to the service providers. I had compassion for the people on the street, but didn’t want to intervene in anyone’s karmic destiny. After all, isn’t this what they asked for in this life”¦to learn what they needed to learn to advance spiritually? That’s what I believe about myself. Any suffering I’ve endured has propelled me deeper into a spiritual practice. Closer to God. Deeper into devotional service. That’s the point” isn’t it?

I follow the devotees around the corner past the Midnight Mission to San Julian Street between 6th and 7th. San Julian is the notorious block where bodies were 3 and 4 deep on the sidewalk, half-naked people sprawled out, shooting drugs into open wounds, smoking crack, mentally ill, under age, anything goes, the predatory population, the dealers, dealing in the open-air drug market. This was a few months back before the Safer Cities Initiative put 50 new cops on the beat and implemented a forced migration of the tent encampments that were overwhelming skid row. These days it’s a little more orderly. It’s still there, but micromanaged by the LAPD.

Skid Row is a metaphor of broader human problems mirrored all over the planet: How we treat each other; How our larger consciousness is reflected by the people we elect. The meta message of Skid Row in Los Angeles is that we don’t care about those who have fallen through the cracks of society.

“My first experience spending time on Skid Row was in 1972 when I stood on street corners chanting Hare Krishna,” Nrsimhananda says. “We used to visit the area once a week and distribute prasadam (spiritual food) to the “less fortunate.” We were outsiders, and so were they. We opted out of the 9-5 rat race; so had they. We slept on the floor; they were asleep on the sidewalk. We liked to get high on chanting the names of God; they had their drug of choice. We had a lot in common, and everybody there seemed to accept and appreciate us then – as they do now. Re-visiting the area 35 years later, nothing much has changed except we almost all seem to have found that mattresses are more of a necessity than a luxury. The missions are a testament to the help that has been blessing the transients for a few decades already.”

And though that’s true, you’ve got to wonder what the hell skid row is still doing here. There’s no shortage of help, money, food. We’re not in Sri Lanka. There are discarded clothes and food all over the gutters down here. Clearly, anyone who wants to go into a program at one of the missions will have dental, medical and social services, as well as spiritual assistance at their disposal. But you have to be willing to make the choice; People living on the streets of skid row are not all in a condition to make choices that are in their best interest, so it would seem.

“The teachings of the Bhagavad-Gita devote much of a chapter to the issue of charity – in the modes of goodness, passion, and ignorance,” Nrsimhananda tells me. “There is detailed information about the subtleties of proper philanthropy. Charity in the mode of ignorance is to be given up. Giving money to a person who will use it to buy drugs or alcohol is a waste. Charity that does not nourish the soul but only the body is also prohibited,” he says, and cites the Gita.

“Chapter 17, Verse 20. That gift which is given out of duty, at the proper time and place, to a worthy person, and without expectation of return, is considered to be charity in the mode of goodness.”

The operatives being proper time and place. The missions make thousands of meals a day by professional chefs in huge modern kitchens, but feeding everyone on skid row hasn’t altered the situation on the street. I consider whether it’s a good idea. I also consider that if I found myself out of a house and a job with no resources that I’d be grateful for their charity.

“Chapter 17, Verse 21,” Nrsimhananda continues, “But charity performed with the expectation of some return, or with a desire for fruitive results, or in a grudging mood, is said to be charity in the mode of passion.”

That seems obvious enough. If you profit from skid row with the wrong intentions, God only knows what kind of karma you’re racking up.

“Chapter 17, Verse 22. And charity performed at an improper place and time and given to unworthy persons without respect and with contempt is charity in the mode of ignorance.”

Which brings us to the issue: How do I help somebody? What are my checks and balances to ensure that I am operating in the right mode and not out of ego? How do you help somebody who doesn’t want it? Is it helpful to feed someone sleeping in the gutter or is it charity in the mode of ignorance? Would it be more enlightened to force them to check into a mission whose program includes a program of self-improvement? There are some who think so and want to impose a homeless court system that would enable authorities to pluck them off the street. It’s a complicated concern with no clear answers.

Anyone who is sleeping in a box on the streets isn’t capable of making great choices for themselves. But it becomes a larger issue, as many people have said: clearly the measure of any society is how we treat our most vulnerable members (paraphrased from Ghandi).

The question is how to really help. I already feel I’m compassionate and tolerant. So, what can I do personally? What can we do collectively? The possibilities are as expansive as the complicated geography. I offer: Talk about it. Read about it. Meditate, chant, say a prayer, write a check, call a congressman, call a mayor, go to a benefit, go to skid row and talk to someone who is living on the street, meet the people, invest in a collective consciousness that says compassion is essential. Embrace the community. Love them. Include them. Hold it in your heart that we emerge as a society that practices a practical compassion for everybody. Hope. Wish. Add to this list.

“Only Krishna’s summary of such altruism crosses my mind,” Nrsimhananda says:

Acts of sacrifice, charity and penance are not to be given up; they must be performed. Indeed, sacrifice, charity and penance purify even the great souls. ––His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2002-2007

LA Yoga Ayurveda & Health Magazine