When Human Rights Extend to Nonhumans

By Donald G. McNeil Jr. | Jul 19, 2008

If you caught your son burning ants with a magnifying glass, would it bother you less than if you found him torturing a mouse with a soldering iron? How about a snake? How about his sister?

Does Khalid Shaikh Mohammed — the Guantánamo detainee who claims he personally beheaded the reporter Daniel Pearl — deserve the rights he denied Mr. Pearl? Which ones? A painless execution? Exemption from capital punishment? Decent prison conditions? Habeas corpus?

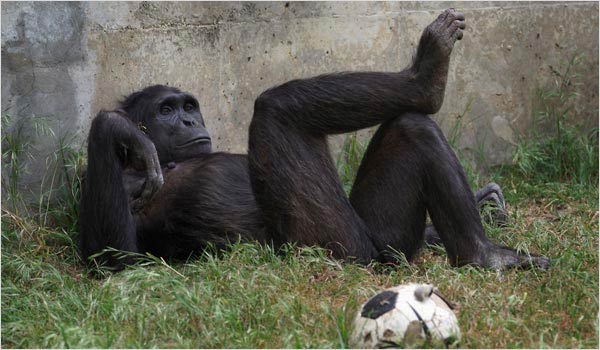

Such apparently unrelated questions arise in the aftermath of the vote of the environment committee of the Spanish Parliament last month to grant limited rights to our closest biological relatives, the great apes — chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans.

The committee would bind Spain to the principles of the Great Ape Project, which points to apes’ human qualities, including the ability to feel fear and happiness, create tools, use languages, remember the past and plan the future. The project’s directors, Peter Singer, the Princeton ethicist, and Paola Cavalieri, an Italian philosopher, regard apes as part of a “community of equals” with humans.

If the bill passes — the news agency Reuters predicts it will — it would become illegal in Spain to kill apes except in self-defense. Torture, including in medical experiments, and arbitrary imprisonment, including for circuses or films, would be forbidden.

The 300 apes in Spanish zoos would not be freed, but better conditions would be mandated.

What’s intriguing about the committee’s action is that it juxtaposes two sliding scales that are normally not allowed to slide against each other: how much kinship humans feel for which animals, and just which “human rights” each human deserves.

We like to think of these as absolutes: that there are distinct lines between humans and animals, and that certain “human” rights are unalienable. But we’re kidding ourselves.

In an interview, Mr. Singer described just such calculations behind the Great Ape Project: he left out lesser apes like gibbons because scientific evidence of human qualities is weaker, and he demanded only rights that he felt all humans were usually offered, such as freedom from torture — rather than, say, rights to education or medical care.

Depending on how it is counted, the DNA of chimpanzees is 95 percent to 98.7 percent the same as that of humans.

Nonetheless, the law treats all animals as lower orders. Human Rights Watch has no position on apes in Spain and has never had an internal debate about who is human, said Joseph Saunders, deputy program director.

“There’s no blurry middle,” he said, “and human rights are so woefully protected that we’re going to keep our focus there.”

Meanwhile, even in democracies, the law accords diminished rights to many humans: children, prisoners, the insane, the senile. Teenagers may not vote, philosophers who slip into dementia may be lashed to their beds, courts can order surgery or force-feeding.

Spain does not envision endowing apes with all rights: to drive, to bear arms and so on. Rather, their status would be akin to that of children.

Ingrid Newkirk, a founder of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, considers Spain’s vote “a great start at breaking down the species barriers, under which humans are regarded as godlike and the rest of the animal kingdom, whether chimpanzees or clams, are treated like dirt.”

Other commentators are aghast. Scientists, for example, would like to keep using chimpanzees to study the AIDS virus, which is believed to have come from apes.

Mr. Singer responded by noting that humans are a better study model, and yet scientists don’t deliberately infect them with AIDS.

“They’d need to justify not doing that,” he said. “Why apes?”

Spain’s Catholic bishops attacked the vote as undermining a divine will that placed humans above animals. One said such thinking led to abortion, euthanasia and ethnic cleansing.

But given that even some humans are denied human rights, what is the most basic right? To not be killed for food, perhaps?

Ten years ago, I stood in a clearing in the Cameroonian jungle, asking a hunter to hold up for my camera half the baby gorilla he had split and butterflied for smoking.

My distress — partly faked, since I was also feeling triumphant, having come this far hoping to find exactly such a scene — struck him as funny. “A gorilla is still meat,” said my guide, a former gorilla hunter himself. “It has no soul.”

So he agrees with Spain’s bishops. But it was an interesting observation for a West African to make. He looked much like the guy on the famous engraving adopted as a coat of arms by British abolitionists: a slave in shackles, kneeling to either beg or pray. Below it the motto: Am I Not a Man, and a Brother?

Whether or not Africans had souls — whether they were human in God’s eyes, capable of salvation — underlay much of the colonial debate about slavery. They were granted human rights on a sliding scale: as slaves, they were property; in the United States Constitution a slave counted as only three-fifths of a person.

As Ms. Newkirk pointed out, “All these supremacist notions take a long time to erode.”

She compared the rights of animals to those of women: it only seems like a long time, she said, since they got the vote or were admitted to medical schools. Or, she might have added, to the seminary. Though no Catholic bishop would suggest that women lack souls, it will be quite a while before a female bishop denounces Spain’s Parliament.

But we’re drifting from that most basic right — to not be killed for food.

Back to the clearing. As someone who eats foie gras and veal (made from tortured animals) and has eaten whale (in Iceland), I don’t know why I suddenly turned squeamish when offered a nibble of primate. On reflection, I probably faked that too. When I was young, my family used to drive over Donner Pass each year to go camping, and my mother would regale us with the history of the Donner Party. Even as a child, I had no doubt that, in extremis, I would have tucked in.

On our drive back to Cameroon’s coast, my guide insisted that some of the local Fang people, well known for cannibalism in the 19th century, still dug up bodies to eat. I believed him partly because in South Africa, where I then lived, murder victims were often found missing the body parts needed in traditional medicine.

Cannibalism is repugnant to the laws of all countries. But that repugnance is not written in the extra tidbits of DNA that separate us from chimps. Quite the opposite: “pot polish” on human bones found in various archaeological sites suggests that some of our ancestors exited this world as stew. That too puts us in the “community of equals” with apes; female chimpanzees are known to eat rivals’ babies.

But when human law does intervene in this primate-eat-primate world, it is also on a sliding scale. Even animal cruelty laws have a bias toward big mammals like us. For example, in a slaughterhouse, chickens are sent alive and squawking into the throat-slitting machine and the scalding bath.

But under the federal Humane Slaughter Act, a cow must be knocked senseless as painlessly as possible before the first cut can be made.

Which raises an interesting moral dilemma for the righteous Spanish Parliament: What about bullfighting?

As in all great struggles separating man from beast: a lot of it’s in the capework. Olé!