A Hindu Mourns the Newtown Tragedy

By Vineet Chander (Vyenkata Bhatta Das) | Dec 27, 2012

I first learned of the tragic shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, while on my way to work. One of my fellow commuters shared whatever scant details were known at that time with the rest of the train car. There were gasps and exclamations, and then we all fell silent. My mind raced, viscerally, to my daughter–who would be in her own preschool class in a few hours–and to my wife, an elementary school teacher. What if it had been them? I chided myself for thinking in this way, both because it was so painful and because it seemed so self-centered. But I couldn’t shake the thoughts. And so I reflected, and then grieved, from where I sat — as a parent.

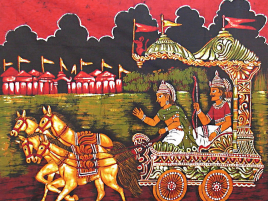

Arjuna, the warrior prince who is Krishna’s dialogue-partner in the Bhagavad Gita, is also a parent — although that is the not the role he is most often remembered for. After hearing Lord Krishna’s treatise on the nature of spiritual reality and the eternality of the self, and the virtues of following one’s Dharma even in the most trying of circumstances, Arjuna agrees to again pick up his bow and fight in the war. A few days later, Arjuna’s son Abhimanyu, one of the youngest and most courageous warriors on the battlefield, is brutally slain. Arjuna reacts as a parent would: he weeps, he beats his fists against his chest, he curses, he grieves.

Many years ago, one of my teachers was asked about this episode. A particularly well-read, if not cynical, Indian journalist challenged him: “Swamiji, Krishna teaches Arjuna that the soul, the true self, can never be killed and that the body is simply a temporary vehicle. But when his son is killed, Arjuna forgets all this and weeps. Isn’t this inglorious?” The elderly teacher answered strongly: “No! It is not that a devotee of God becomes like a stone, hard-hearted and devoid of emotion. A devotee feels all emotions. If his son is killed, he experiences pain and he grieves. This is his glory. He grieves for his son, and still he follows his Dharma.”

How might a Hindu experience and share in the nation’s grief in the wake of the tragedy in Newtown? We can grieve as Arjuna did, and support others to do the same. The Gita’s sixth chapter (6.32) describes this as the hallmark of one who has reached the highest stage or deepest realization of yoga: such a person celebrates the happiness of others as his own, and experiences the pain of others as he would his own. Of course, to maintain such a state of radical empathy and compassion is admittedly difficult. We can, however, at least aspire towards it. We can think of our children, or partners, or loved ones, and ask What if it had been them?

Why do such unspeakable tragedies take place to begin with? Hinduism, like other spiritual traditions, offers us a great deal of philosophical insight to grapple with the question. The doctrine of karma provides some way to make sense of the seemingly meaningless, but also raises problems of its own. The idea that this material world, home to suffering born of selfishness, greed, anger, and madness, is an illusory construct and artificial imposition on our true spiritual essence is, technically speaking, true — but provides little practical comfort. Moreover, unless we have the requisite spiritual maturity and sensitivity, our answers will probably ring hollow and cold. We may even philosophize our way out of our humanity, or excuse ourselves from what is needed most — to be present and genuinely share in the pain of others. Let us resist that temptation.

It is said that, at times like this, a nation grieves as one. President Obama echoed this sentiment concisely when he told Newtown, “You are not alone.” This is the challenge to Hindu-Americans. One of the pillars of Hinduism is the idea of ekatva, a sacred oneness that binds all beings in creation. We can find, within this tragedy, an opportunity to live out this idea; we can shed ekatva of its abstractness and transform it into a powerful offering of comfort and support to a community, and a country, that so desperately needs it.