Devotees on the Frontlines of COVID-19: Chaplain Ghanashyam Das

By Madhava Smullen | May 19, 2020

When Ghanashyam Das first began his chaplaincy service in New York City, little did he know that he would end up on the frontlines of a global pandemic, risking his own health every day to provide spiritual and emotional support for patients dying of Coronavirus.

Ghanashyam, now 42, joined ISKCON in 2000 at 26 2nd Avenue in New York, the movement’s first ever temple. Later, he moved to the Bhakti Center in Manhattan, where he lived as a monk for eleven years, and where his empathic nature saw him serve as counselor and mediator for his fellow brahmacharis.

This led to a post as assistant chaplain at Columbia University, and then, at students’ request, as official chaplain at NYU. So when he decided to change ashrams and move into family life, it made sense to Ghanashyam to learn how to do what he loved for a living.

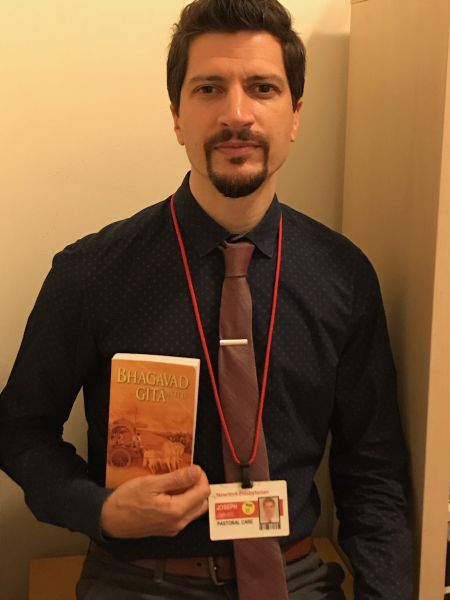

Beginning in 2014, he took a year of Clinical Pastoral Education at Belleveue Hospital, which included training through regular patient visits as well as academic processes to learn listening and empathy skills. He then interviewed for a paid chaplain residency at New York-Presbyterian Hospital – ranked the number one hospital in New York City, and number five in the nation – and was hired the very same day.

Upon conclusion of his one-year residency, the supervisor of the chaplaincy program liked Ghanashyam so much that she created a position for him as assistant to the supervisor, helping to train new residents. Finally, in 2018, he was hired as a full-time palliative care chaplain at the main branch of New York-Presbyterian in Manhattan, tending to patients suffering from serious illnesses or dying.

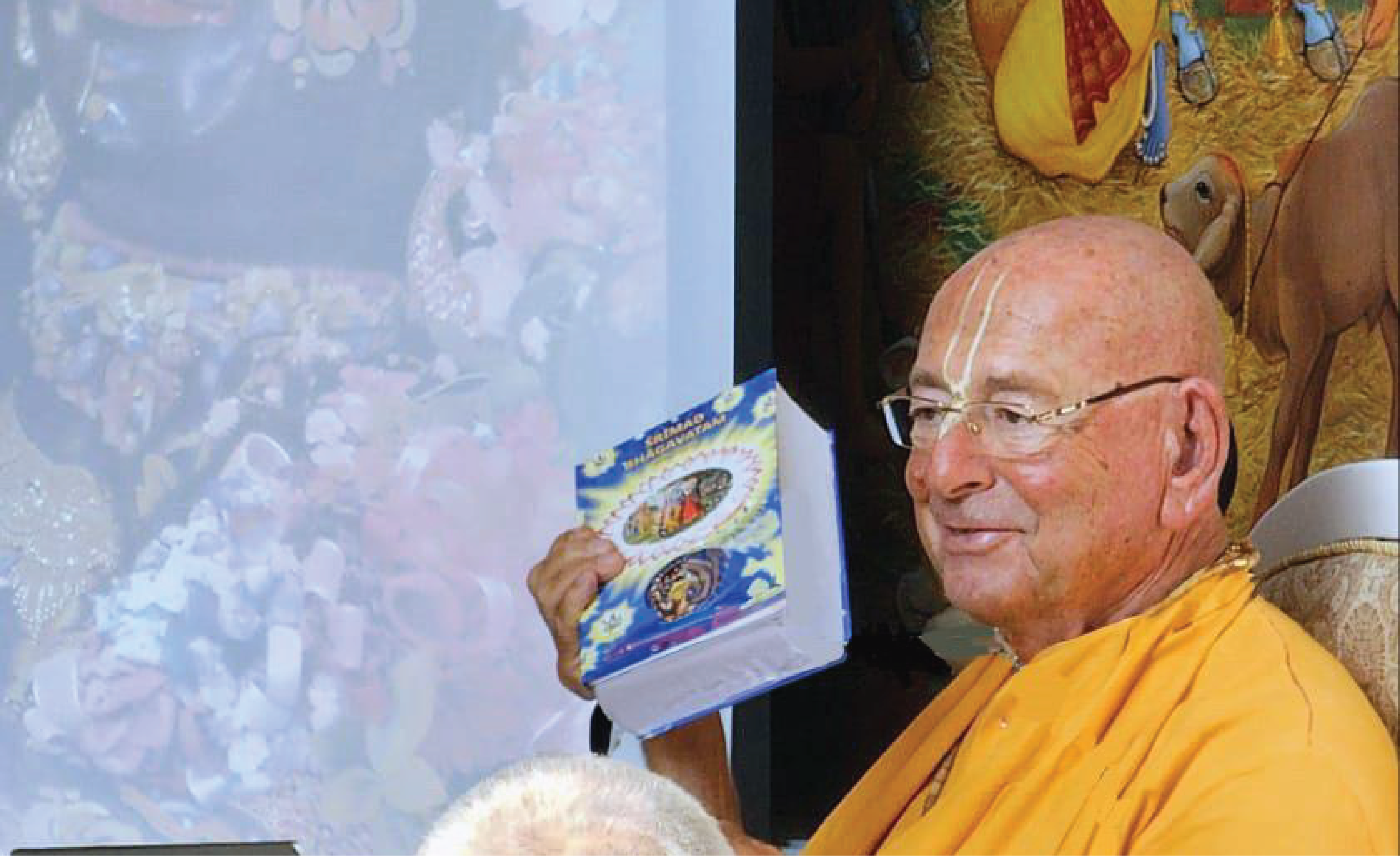

New York-Presbyterian Hospital chaplain Ghanashyam Das

Caring for Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic

During normal times, Ghanashyam would start his day by meeting with the team that provided focused care for palliative care patients, consisting of a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, a psychiatrist, and a chaplain.

The team would give each other referrals, and then Ghanashyam would check in with every patient on his list, asking if he could support them by bringing them spiritual resources, a chaplain from their own religion, or if they would just like to talk. Normally, he would spend weeks or months with the same patients, conversing with them and building a relationship.

But after the COVID-19 pandemic hit, everything changed. The U.S. sustained the most known Coronavirus cases in the world, and New York state the most confirmed cases of any state in the U.S. More than half the state’s cases, meanwhile, are in New York City.

This vastly impacted Ghanashyam’s work as a chaplain.

At one point, the number of palliative care patients in his hospital at a time jumped from twenty-five to nearly ninety, about eighty percent of them Coronavirus patients.

“It was so overloaded, we could hardly handle it,” says Ghanashyam, who spends most of his days on COVID positive units. “We only have two small palliative care teams of five or six, so there are just two palliative care chaplains in the whole hospital. It became hectic and intense. We had to move from one patient to the other much more quickly.”

Although hospices usually exist as a separate facility, so many new patients were sick and dying that the hospital opened its own hospice unit to care for them. And while hospice care is usually recommended for those who are given six months or less to live by doctors, most Coronavirus patients in the hospice unit of New York-Presbyterian Hospital die within hours to days.

What’s more, because they are extremely sick, and most of them are intubated and placed on ventilators, Ghanashyam can’t converse with them as he usually did. “So I just go in the room and pray or chant Hare Krishna for them,” he says.

If patients of non-Hindu religions don’t request a chaplain of their own faith, Ghanashyam reads their main spiritual scripture, or delivers a broader prayer for them. “Dear God,” he prays, “This is a very precarious and scary situation, and we ask that your protection is upon this person, that you’re here with him, and that he can experience your presence. Please empower the nurses and doctors to do their best work to help him. And please allow him to experience love coming from his family and your own divine love, whatever his body may be experiencing.”

By mid to late March, Coronavirus infections became so widespread that the hospital no longer allowed chaplains to enter patients’ rooms; this remains in place today. “The best I can do is stand outside the room and chant or pray,” says Ghanashyam.

Earlier on in the pandemic, in a tragic turn of events families could not even visit their dying relatives. During this time, Ghanashyam would call patients’ family members on an iPad so that they could talk and connect visually with their loved ones.

Fortunately, since early April – when the hospice unit became fully functional – select family members have been able to visit at scheduled times, with appropriate precautions.

Of course, some patients do not have family to visit them; but they always have Ghanashyam.

“I live just a ten-minute walk from the hospital, so I told the nurses, if anybody’s dying alone, call me, and I’ll come in,” he says. “There have been times when I’ve just sat with a patient and chanted Hare Krishna to them or prayed for them the whole time, so they don’t die alone without any support.”

Taking Shelter of Krishna

For Hindu or Jain patients, and particularly for devotees of Krishna, Ghanashyam is able to make special arrangements: he reads from the Bhagavad-gita to them, chants with them, and brings them prasadam, Ganga water, Tulasi leaves and pictures of Krishna.

Among these patients are the large Guyanese and Trinidadian population of Queens, who have shown their deep love for Lord Krishna.

When Ghanashyam asked one Hindu man in his late seventies who was dying if he had anyone he needed to talk to, or anything he needed to resolve, he responded, “I have no regrets. I’ve had my family, and my devotion to God, and I feel like there’s nothing in the way.”

“If you have nothing else to accomplish, and you know you have just a short time left,” Ghanashyam advised the man, “Then all you have to do is focus your mind on Krishna.”

“How do I do that?” asked the patient, who was a pious Hindu but had not had a regular spiritual practice throughout his life.

Ghanashyam experimented with different methods, bringing the man japa beads and chanting with him, then reading the Bhagavad-gita to him; but neither practice seemed to connect.

“Finally, I had the idea to bring him a picture of Sri-Sri Radha Muralidhara from the Bhakti Center,” Ghanashyam says. “I put it on the wall in his room, and as soon as he saw it, he was blown away by how beautiful it was.”

“That picture changed everything. He started praying to Krishna, and when his family would come to visit, they’d immediately go to the picture, bow their heads and fold their palms. They began bringing him fruits to offer. The whole atmosphere transformed.”

“I wasn’t there when he passed away because it happened overnight,” Ghanashyam continues. “But his wife later told me that he was looking at the picture, and motioned to her to take it down and give it to him. She took it off the wall and put it in his hands. He held the picture form of Radha Murlidhara to his face, then to his heart. And he passed away embracing Them. It was incredible.”

The Purifying Power of Suffering

In his work as a chaplain, Ghanashyam has developed faith in the transformative power of suffering.

“When I’m with patients, I’m not always trying to stop their suffering, give them good news, and tell them it’s all going to be fine,” he says. “I trust that it can open up a power that’s normally not there. And I have faith that sickness can make people reflect, and make them more mild and humble. Some people turn to God more, some reflect on their life, the mistakes they’ve made, or things they would like to change. There’s a purifying power that’s not usually available. So I’m not so much afraid of suffering. Instead I say, let me step into it with them and be supportive, and see what happens.”

Supporting Families Through Grief

Another important part of Ghanashyam’s job is supporting patients’ families and guiding them through their grief over the phone.

To do this effectively, he prepares himself by entering into a mindset of empathy. “I think about the background,” he says. “That this person’s father was healthy, and out of nowhere, he got this disease and now he’s in the hospital and very likely to die. So let me enter into his son’s world and realize how stressful, difficult and scary it must be for him.”

When Ghanashyam calls family members and tells them he’s there for them if they want to talk, most open up and share. Many express their appreciation and give him blessings when he tells them he visits and prays for their relative every day. Often, they cry, unsure of what to do, and Ghanashyam listens very carefully, empathizes, and holds the space for them.

Although it’s difficult, he also has to be able to detach himself afterwards. “When I’m talking with them, I get into it fully, and when I hang up the phone, I completely let it go,” he says. “Because it’s not healthy to keep it all.”

Dealing With Fear

While visiting COVID-positive patients all day, Ghanashyam wears gloves, a mask with protective eye shield, and a protective gown that covers his whole body down to the shins. At first, he felt secure that he was taking all possible precautions, and therefore safe.

But one night, the fear began to get to him. “I woke up in the middle of the night feeling very hot, and thought, ‘Oh man, is this a fever? Am I getting the symptoms?’” he recalls. “I started freaking out – ‘My wife is here, is she going to get sick now?’ I became really nervous and couldn’t get back to sleep. And I remember looking at all Prabhupada’s books on my shelf and thinking, ‘How much of this knowledge have I really internalized? When we die, we just have the consciousness we’ve cultivated throughout our life. I have to go deeper into these books.’”

The next morning, Ghanashyam did not feel ill anymore. And having had such powerful realizations about death, he decided to simply face his fear. “I thought, ‘I’m not going to hide at home, this is my work,’” he says. “I might get sick, but if I do I’ll accept it and deal with it.’ And once I decided to just walk through the fear and accept whatever consequences were going to come, that’s when the fear started to reduce. Now I feel great about it. If I’m going to do this work, I might as well do it fully, and not resist it.”

The Greatest Opportunity to Serve

Although the number of palliative care patients at the main branch of New York-Presbyterian is now beginning to fall every week, down from a height of nearly ninety to somewhere in the sixties, Ghanashyam’s work is far from over.

The blessings of patients and their families give him the strength to continue, as does the opportunity for spiritual growth.

“I see this as a practice for dying,” he says. “Because eventually, Coronavirus may go away, but disease will not. Some form or other will be there, and at some point, it will come to me and the people I love too. So this is an opportunity to face those scary things in the heart with integrity; to prepare myself, get in the right mindset and face it without letting fear stop me.”

Ghanashyam is also taking shelter of a quote by Srila Bhaktivinode Thakur: “Wherever there is the greatest need, there is simultaneously the greatest opportunity to serve.”

“I think a lot about that statement,” he says. “There is a great need right now, and I feel like I should seize this opportunity to be there for people and help them at this time.”