India’s Vedic Revival

By Sankirtana Das (ACBSP) | Feb 21, 2024

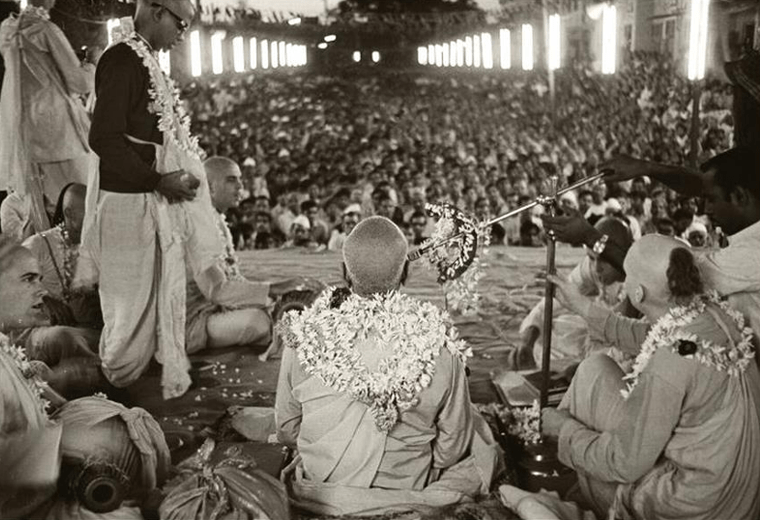

Srila Prabhupada preaching to a large crowd in India.

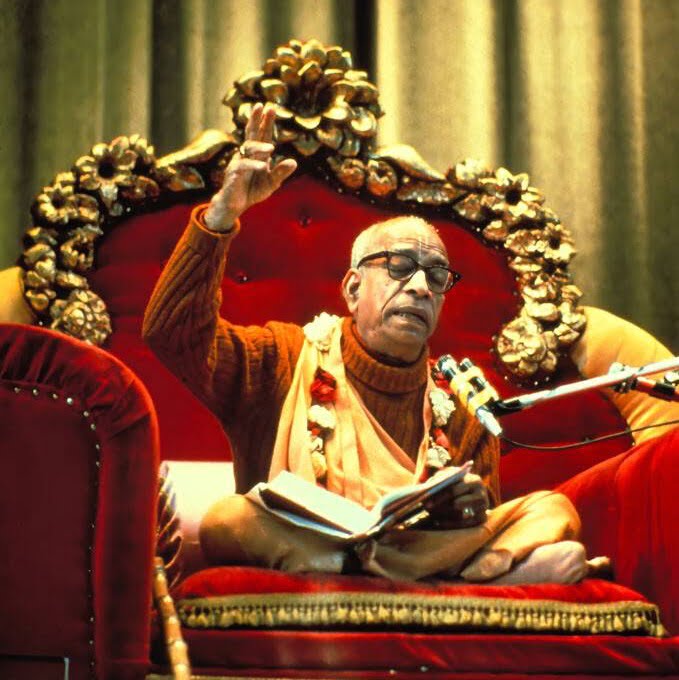

Srila Prabhupada, founder of the worldwide Hare Krishna Movement, vigorously presented the Vedic culture and the teachings of Sanatana Dharma throughout the world in the last ten years of his life. This was a monumental and singular achievement for a man who had not stepped outside of India until his 70th year. In 1965, Prabhupada obtained free passage on a cargo ship and arrived in the USA with only a few dollars in his pocket and no financial backing. In coming to the West, Prabhupada wanted to fulfill his guru’s final request in 1936 to take the teachings of Sri Krishna to the English-speaking world. Prabhupada also sought to lay the foundations for a renewal of Sanatana Dharma in India as well.

For over a hundred years, the Western view of India has been one of severe poverty: people eking out an existence on the streets of India’s big cities. Yet, Western historians are clear about India’s greatness and know all too well how the invasions of India and British colonialism had devastated its economy and culture. For example,

“If I were asked under what sky the human mind has most fully developed some of its choicest gifts, has most deeply pondered on the greatest problems of life, and has found solutions, I should point to India.” – Max Mueller

“India was a far greater industrial and manufacturing nation than any in Europe or than any other in Asia. Her textile goods – the fine products of her looms, in cotton, wool, linen, and silk – were famous over the civilized world.” – J. T. Sunderland

“India was the motherland of our race, and Sanskrit the mother of Europe’s languages: she was the mother of our philosophy…mother, through the village community, of self-government and democracy.” – Will Durant

In 1835, the English Education Act was instituted. At the time, there were over 700,000 village schools in India. Schools were banned, as was the teaching of Sanskrit. Rather than supporting the efforts of local schools in their local languages, one thousand schools and colleges were established in the 19th century, with all classes conducted in English. Thomas Macaulay, one of the Act’s main framers, saw this as a way to turn the more intelligent Hindus away from their culture. He explained the new school system must create “a class of persons, Indian in blood and color, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.” In this way the English overview would gradually be disseminated into the rest of the Indian population. In a letter to his father, Macaulay boasted that the English schools will educate children who won’t “know anything about their country. They won’t know anything about their culture, they won’t have any idea about their traditions…”

These so-called centers of learning served to indoctrinate Hindus into believing that their Vedic culture arrived with the Aryan “invaders” who came to India from some undetermined place, that their esteemed Vedic scriptures were merely fables and myths, and that the Indian economy was enhanced, rather than actually destroyed, by British manipulations. The British even commissioned a Hindu author, N.N. Ghose, to write a book entitled “England’s Work in India” (1909), glorifying the British and their administration of India. It was used as a text in the school system. Their Aryan invasion theory helped the British claim that they had a right to be there since India had always been in the crosscurrents of different invasions over thousands of years. Through these schools, religious conversion to Christianity became an increasingly strong cultural element of British rule.

In a letter dated September 18, 1976, Srila Prabhupada explains the essence of Ghose’s book, “…that we are uncivilized and the British had come to make us civilized. Later on, the policy became successful because in our childhood days, any Anglicized gentleman was considered to be advanced in civilization…(and now) our leaders are not very serious to revive our own culture.” But Prabhupada’s letter is hopeful. He concluded, “if we revive Krishna consciousness in a systematic way, within a very short time we can revive our original Indian culture on the basis of the teachings of Lord Krishna and the Bhagavad-gita.”

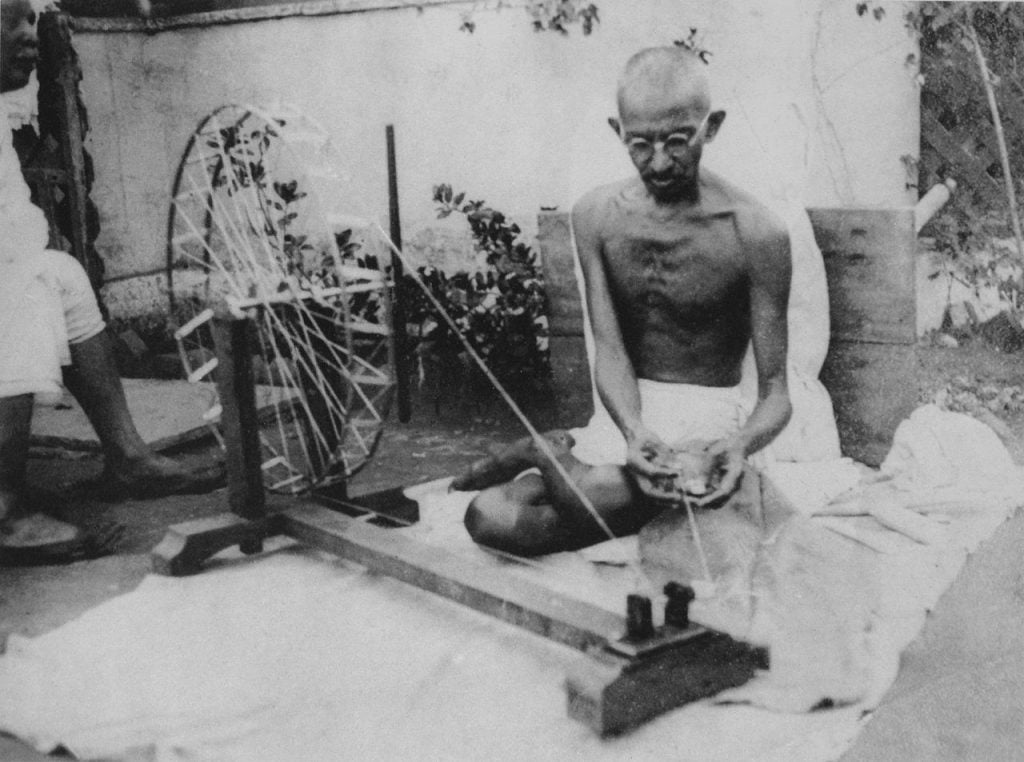

The British strategy of indoctrination continued for over a hundred years, through India’s independence in 1947 and beyond. Jawaharlal Nehru became India’s prime minister for the first 16 years of its independence. Although he, along with Gandhi, rejected British rule, Nehru did not reject his British training and the Western materialistic worldview. Gandhi wanted to overcome the caste divisions which the British had actually encouraged. He wanted to quell the divisions between religions and political ideologies. He wanted to revitalize village life. Gandhi saw India’s strength in its village culture: producing their own food, cloth, and pottery and living a peaceful lifestyle. In June of 1974, Prabhupada spoke to the World Health Organization in Geneva, making these very same points about village self-sufficiency.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Nehru, as opposed to Gandhi, wanted to compete in the world on the West’s terms rather than on India’s natural strengths. He wanted to industrialize India as quickly as possible. He, along with many other educated Indians, concluded their spirituality was inhibiting the material progress of the nation. Nehru proclaimed the dams and factories as the “new temples of modern India.” He saw that the answer for the future growth of India resided simply in a continued and strengthened secular education.

Nehru was delighted to find a 4th-century BC Sanskrit text called “Artha-shastra.” The book contains many chapters on various material arts: politics, economics, military strategy, etc. Nehru touches upon its core philosophy in his own book “The Discovery of India” (p. 97), “Their general spirit was comparable in many ways to the modern materialistic approach; it wanted to rid itself of the chains and burden of the past, of speculation about matters which could not be perceived, of worship of imaginary gods. Only that could be presumed to exist which could be directly perceived, every other inference or presumption was equally likely to be true or false. Hence matter in its various forms, and this world could only be considered as really existing. There was no other world, no heaven or hell, no soul separate from the body. Mind and intelligence and everything else have developed from the basic elements.”

In 1958, Prabhupada sent Nehru a letter advising him to readjust his vision for India. Prabhupada wrote that “materialism conducted with an aim of reaching spiritual perfection is the right adjustment of human activity. If the aim of spiritual realization is missed, the whole plan of materialism is sure to be frustrated…The history of the West beginning from the time of the Greeks and the Romans down to the modern age of atomic war— is a continuous chain of sense gratificatory materialism, and the result is that the Westerners were never in peace within the memory of 3000 years of historical records. Neither it will be possible for them at any time in the future to live in peace if the message of spiritualism, just suitable to the present age, does not reach their hearts.”

In his lectures and discussions in the West, Prabhupada often touched upon the history and struggles of India, giving his Western disciples a more tangible understanding of these blatant attacks on Dharma. On a morning walk in Durban (October 1975), Prabhupada stated that the purpose of British policies of the colonial era was “to kill India’s culture.” On the walk, Prabhupada discussed Macaulay, Nehru, and Gandhi and how the British lured innocent villagers into the big cities, creating a population living on the streets. He also explained that Sanatana Dharma is not only for Hindus but for everyone.

In various discussions and lectures, Prabhupada touched upon India’s wealth. Indians were expert shipbuilders, and their traders traveled to distant ports a thousand years before Moslems or Europeans arrived in India. India’s exports were far greater than other countries. He also noted that the “artificial partition,” which made Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh into separate countries, exasperated the troubles between Hindus and Muslims.

In 1970, as Srila Prabhupada left Japan to go to India, he told his disciples, “I have opened the West. Now I will take my dancing white elephants (his western devotees) to India.” Brahmananda, one of Prabhupada’s early disciples, understood that “the mission was to have the Indian people become devotees.” In the early days of the Krishna Movement, Prabhupada would often say, “I am the only Indian.” When he spoke to Hindu audiences, he often implored them to join this revival of Vedic culture one way or another; his repeated request, “Do not neglect your culture, the Vedic culture.”

In a conversation with a London reporter (March 1975), Prabhupada relates that some Indians claim to be Hindus but are not following their Vedic teachings, just as Westerners claim to be Christian but do not follow the teachings of Jesus. He ended, “This is going on all over the world…This is the position of the modern Hindus. They have lost their own culture, and they wanted to imitate Western culture.”

In Bombay (November 1975), Prabhupada frankly tells an Indian gentleman, “Your forefathers might have been misled, but why you will commit the same mistake again?” Prabhupada explained that although his Western disciples had taken to spiritual consciousness, the Indians were not yet prepared to take up their own culture. For the most part, since the colonial era, many Hindus have neglected their spiritual heritage. Prabhupada’s conclusion is, “They are sleeping.” The revitalization of the sacred Vedic culture and knowledge in India was certainly a core element of Prabhupada’s worldwide mission.

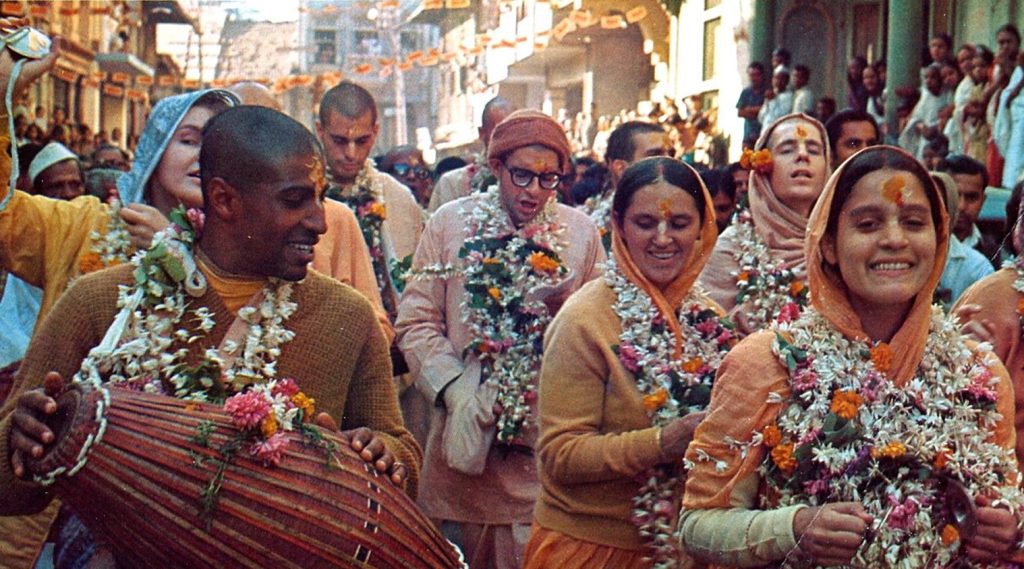

ISKCON devotees chanting in the streets of India, being garlanded by appreciative Indians.

Srila Prabhupada passed away in 1977 in Sri Krishna’s holy town of Vrindavan. Prabhupada’s message, along with his ISKCON temples, gradually impacted the people of India. When Western devotees traveled there (myself included), Hindus would often exclaim, “You are following better than us.” By the mid-1990s, Hindus began to openly question the education the British had left them with, an education that undermined their culture. For example, the concocted Aryan invasion theory, that their scriptures were fables, or the ludicrous notion that the British had uplifted their economy and culture.

During the colonial era and well into the 20th century, hardly anyone in India could comprehend the almost irreparable damage the British had caused. In his travels and presentations, Prabhupada vigorously made points about India’s history and heritage that no one else was speaking about at the time.

It was only later that scholars and researchers began to re-examine their history, culture, scriptures, and all the various facts and figures at their disposal. Discussions, conferences, and events in India and abroad ensued (I was invited to make presentations at some in the USA). And looking back now, I think Prabhupada hit the mark. His appeals to the Indians certainly influenced their renewed interest in the Vedic culture and Sanatana Dharma.

Unfortunately, we see religion being politicized and weaponized both in the East and the West. Very often, religions are associated with nationalistic movements. In India, of course, Hinduism is the dominant religious tradition. But by its very nature, Sanatana Dharma transcends Hindu Nationalism. Hindus have certainly endured much hardship. And on the strength of their spiritual heritage and their undying connection to their great epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, the Indian people can show the world that they embody an age-old, enduring culture. This is something to be proud of. But they must carry that pride humbly and conscientiously.

Sanatana Dharma must be approached in this way. For millennia, these profound teachings have attracted wisdom seekers from around the world to India. This has been the subject matter of popular books like “Siddhartha,” “The Lost Horizon,” and “The Razor’s Edge.” Their authors had gone to India and immersed themselves in its culture and ashrams. In the United States, the Bhagavad Gita has been revered for two hundred years, since the time of Emerson and Thoreau. Sanatana Dharma, the Eternal Path, embodies spiritual principles that are universal and meant for all people, and especially for all seekers of the truth. The sages tell us, “When we protect the Dharma, the Dharma, in turn, protects us.”

About the Author

Sankirtana Das (aka Andy Fraenkel), a disciple of Srila Prabhupada, is a longtime resident of the New Vrindaban Community, and an award-winning author and storyteller. His most recent book, Hanuman’s Quest, is acclaimed by scholars and has received a Storytelling World Resource Honors. He also sits on the board of directors for the Vedic Friends Association. At New Vrindaban, Andy offers sacred storytelling and scheduled in-depth tours. This article is the result of research for his new book, a work-in-progress and yet untitled. For more info about his work visit www.Mahabharata-Project.com.