“Make Me Dance”

By Chaitanya Charan Das | Jul 01, 2016

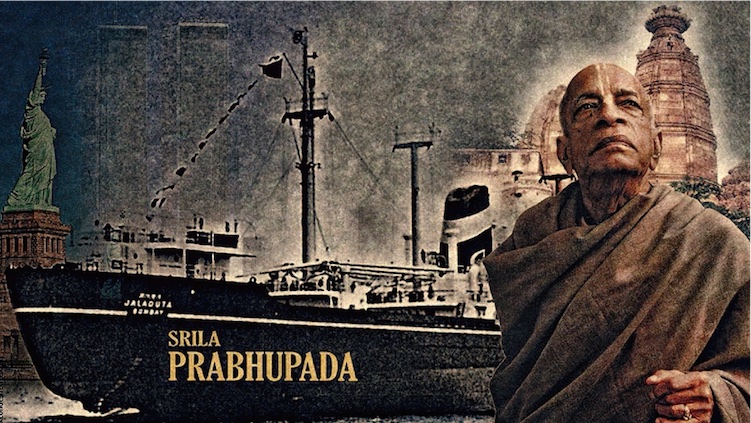

Meditation on Srila Prabhupada’s prayer on beholding the American coastline

In the world’s great wisdom-traditions, prayers are often acknowledged as means for accessing divine power. The prayers by saints often reveal the profound depths of their selfless devotion to God.

One such exalted prayer is the song Markine Bhagavata-dharma (Teaching Krishna consciousness in America) that Srila Prabhupada composed in 1965 while he was aboard the Jaladuta, the ship that had carried him from India to America. However, the ship had only been the physical instrument – what had actually carried him across the ocean was his selfless aspiration to share Krishna’s message of spiritual love with the world. That aspiration had inspired him to embark in the advanced years of his life on a bold journey, alone and penniless. And his journey had turned out to be much more demanding than any normal ship journey. After being initially discomfited by seasickness, he had been afflicted on two successive nights with two devastating heart attacks, which he had to endure without any medical assistance whatsoever. Having weathered both the stormy seas and the deadly heart attacks, he had finally, after a thirty-five-day voyage, reached the coast of America.

On beholding the American coastline, Srila Prabhupada used his mother tongue Bengali to express his heart’s innermost thoughts and emotions in an intimately direct appeal to Krishna. Revealingly, even these spontaneous expressions are rooted in scripture. This natural link between his personal expression and scriptural revelation is evident in his quoting a series of Sanskrit verses from Srimad-Bhagavatam, a devotional classic that is considered one of the most important books in the Sanskrit canon. This is the book whose translation and commentary was to become his life’s magnum opus – a multi-volume rendition whose first three volumes he was carrying with him. These volumes comprise the transcendental arsenal with which he aspired to dissipate the worldly illusions of his audience.

Let’s look verse-by-verse at the meaning and mood of Srila Prabhupada’s prayer-song.

- He begins by expressing his gratitude to Krishna for his immense mercy. Referring to himself with disarming humility as a fallen soul, he confesses his uncertainty about why Krishna has brought him there. And he appeals to Krishna to do with him whatever may be his divine will, an appeal that foreshadows the song’s conclusion. At first glance, there might seem to be little evidence of Krishna’s mercy in Srila Prabhupada’s condition. He is about to disembark in a foreign land without money, contacts or institutional support. He has no guarantee that his sponsor, a person whom he has never met before, will welcome him. Nor does he have any guarantee that his audience would welcome his message. Yet he is grateful. He has at long last got the opportunity to fulfill his spiritual master’s instruction to share Krishna’s message in English in the Western world. Srila Prabhupada had dedicated his life to fulfilling his spiritual master’s instruction. For over forty years, he had strived to share Krishna’s message in India, albeit without much success. And now he has finally got the opportunity to share that message in America.Even if there is no clear way for him to tap that opportunity, he sees just the availability of this opportunity as Krishna’s great mercy. Thus, he demonstrates an inspiring example of counting one’s blessings even when the blessings are sparse and are surrounded by obstacles.

- This verse begins with an even more candid admission of uncertainty, wherein he guesses that Krishna must have some purpose for having got him so far. His uncertainty conveys that even a dedicated devotee whose life is entirely guided by scriptures and sages may not always be sure about how to apply their instructions in this messy world. Being divinely guided doesn’t mean that there can’t be uncertainty about practical action – it means that there won’t be any uncertainty about perennial intention. Srila Prabhupada is determined to serve Krishna, but how exactly he will serve him in this foreign land is unclear and calls for some prayerful inference. Underlying the surface uncertainty is a deep certainty – the conviction that Krishna must be having some plan. Srila Prabhupada points to the difficulty of sharing the bhakti message in America by referring to it with the word ugra-sthana “terrible place.” This is a strikingly atypical assessment of America, which is usually perceived by visitors as the land of opportunity, prosperity and liberty. When Srila Prabhupada sees the American coastline, he sees not material prosperity, but spiritual poverty. Being driven by compassion, he longs to share the treasure of bhakti with not just America but with the entire Western world and indeed the whole world, much of which is afflicted with spiritual ignorance.

- The next verse specifies what is terrible about the land he is approaching: its people are covered by the lower modes of passion and ignorance. The same trappings of worldly prosperity that others might have seen as signs of progress and success, Srila Prabhupada sees as symptoms of severe infection by the lower modes. Such infection makes people materially obsessed and spiritually dulled. The anti-spiritual result of the modes is pointed in the second line: they won’t be able to taste the glories of Krishna, a taste that is the engine of the transformation of character that bhakti stimulates. Srila Prabhupada has seen in India how material infatuation has made his countrymen apathetic to spiritual wisdom. And he apprehends a similar, if not greater, problem in America, with its far greater material allurements. Intriguingly, while assessing the task before him, he doesn’t mention the many other obstacles that would have dominated the thoughts of most sociological observers – obstacles such as unfamiliarity of language, culture and worldview. His overlooking these obstacles signifies his deep abiding faith in the universality and transcendence of bhakti.

- Srila Prabhupada’s transcendental focus is further highlighted in his delineation of the solution to this problem: Krishna’s mercy, which is far more powerful than the modes’ deluding power. He begs for mercy by which his audience will be able to appreciate Krishna’s glories. Acknowledging that changing their disposition from materially infatuated to spiritually attracted is a herculean task, he expresses his full confidence that Krishna’s omnipotence can make it possible.

- Taking this appeal forward, he begs Krishna for mercy so that people will be able to relish the rasa of bhakti. This mention of rasa points to the venerable tradition that Srila Prabhupada represents: Gaudiya Vaishnavism. Rasa, the concept of devotional taste expressed in the language of dramaturgy, is the Gaudiya tradition’s distinctive contribution. Presently, we have taste for various material pleasures. The process of bhakti-yoga centers on purifying our taste, thereby enabling us to relish bhakti-rasa, higher devotional happiness. Thus, bhakti-yoga asks not for a rigid renunciation of pleasure, but for a relishable redefinition of pleasure.

- Srila Prabhupada’s acknowledgement of Krishna’s omnipotence is further evident in his declaration that everything rests on Krishna’s will: By his will, all living beings have come under illusion – and by his will, all living beings can come out of illusion. The defining difference between their bound state and their liberated state is Krishna’s will. Of course, their own desire is important – they need to change their desire from wanting to enjoy independent of Krishna to lovingly harmonizing with his will. Still, this prayer’s purpose is not to exhaustively analyze the philosophical technicalities of all the factors involved in action. The prayer’s purpose is to express Srila Prabhupada’s utter dependence on Krishna. In keeping with this mood, the pertinent point is that Prabhupada attributes to Krishna all doership and all credit for the deliverance of people; he doesn’t think himself the doer or deliverer.

- The next verse reflects a revealing blend of dependence and confidence: If Krishna desires the deliverance of people, they will surely understand the bhakti message. This may raise the question: Doesn’t Krishna always desire the deliverance of everyone? Yes, he does. Again, the point is that Srila Prabhupada doesn’t see himself as the one who will transform people’s hearts; he sees Krishna as the transformer.

- While expressing his total dependence on Krishna’s mercy, Srila Prabhupada is by no means conceiving his own role passively. He intends to dynamically, tirelessly, expertly make Krishna accessible to his audience. How? By speaking bhagavata-katha, an umbrella term that refers to Krishna’s message, pastimes and glories. Significantly, he equates bhagavata-katha with an avatar, a concept that is a defining characteristic of the broad bhakti tradition, a concept that points to the Absolute Truth’s descent into this relative material world. The word avatar usually refers to the Lord’s various descents such as Rama, Narasimha, Vamana and other transcendental forms that periodically manifest in this world. Here Srila Prabhupada refers to a more esoteric connotation of that word: Krishna’s sonic avatar as bhagavata-katha. The nondifference of Krishna and the sound vibrations glorifying him is a central theme of the Bhagavatam. In fact, the Bhagavatam indicates that Krishna descends not only as a sonic avatar but also as a textual avatar – the Bhagavatam, which is replete with bhagavata-katha, is often considered an avatar of Krishna. This textual avatar has ascended like the shining sun to dissipate the darkness of the present age of Kali (1.3.43). Given that bhagavata-katha is Krishna’s avatar, those who hear it repeatedly will be empowered to counter illusion and become spiritually sober.

- To build on this theme of the potency of bhagavata-katha, Srila Prabhupada seamlessly shifts from Bengali to Sanskrit, from self-composed verses to scriptural verses, and from expressing personal emotion to reiterating time-honored revelation. He quotes from a section of the Bhagavatam, which describes the modus operandi of bhakti-yoga, specifically of its fundamental limb – hearing bhagavata-katha. He quotes a series of five verses from Srimad-Bhagavatam (1.2.17-21). In quoting thus, Srila Prabhupada follows the example of prominent exponents of the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition. For example, Krishnadasa Kaviraja Goswami, author of one of the tradition’s foundational books, Chaitanya Charitamrita, intersperses the Bengali narrative with many Sanskrit verses. The specific verses that Srila Prabhupada quotes are revealing, for they delineate how bhakti practice brings about spiritual healing. A doctor, on seeing a devastating epidemic, may recollect the formula for the cure, thereby gaining confidence to combat the morale-crippling magnitude of suffering evident before one’s eyes. Similarly, Srila Prabhupada here recollects and recites these verses that delineate how bhakti-yoga can cure the pandemic of bhava-roga, the disease of material attachments, a disease that sentences eternal souls to repeated misery in the cycle of birth and death. These verses describe how hearing Krishna’s glories is itself pious and activates his purifying potency within our heart (17); how by regular hearing, the inauspicious impurities in our heart are removed and bhakti becomes firmly established (18); how thereafter the lower modes along with their associated drives such as lust and greed disappear, thereby enabling one to become situated and satisfied in the higher mode of goodness (19); and how the subsequent performance of bhakti engenders clear understanding of what Srila Prabhupada translated as “the science of God”, thereby freeing one from attachment (20). The last verse in this sequence describes the liberated state – the knot of attachment in the heart is cut, doubts are eradicated, selfish action is stopped, and the self is seen in its transcendental glory as being beyond matter and beyond the bondage of matter (21). Srila Prabhupada’s quoting these specific Bhagavatam verses indicates that he is not expecting or requesting Krishna to perform any supernatural jaw-dropping miracles that will magically transform his audience. He is simply asking that he be made an agent for the purifying, transforming potency of bhagavata-katha.

- Restating in Bengali the preceding point of the transformational potency, this verse says that by hearing bhagavata-katha, people will become freed from all inner inauspiciousness. Thus, Srila Prabhupada expresses the confidence that bhakti-yoga itself can counter the lower modes that cover his audience.

- Still, inspiring people to keep hearing Krishna’s message till comprehension dawns and taste awakens is a formidable, if not insurmountable, challenge. Acknowledging this, Srila Prabhupada stresses his lack of qualification. Referring to himself as a shudra – not in the material sense associated with the discriminatory caste system, but in the sense of being spiritually disqualified – he declares that he lacks any power to meet this challenge and begs for Krishna’s mercy.

- Intriguingly, Srila Prabhupada follows his statement of his lack of qualification with his statement of firm determination. He declares that he will simply speak bhagavata-katha, leaving in Krishna’s hands the result of such speaking. His simple resolution conveys poignantly the inconceivability of humility in bhakti. Normally, feeling disqualified erodes our determination. Some people even allege that humility is psychologically damaging, breeding feelings of inferiority. It’s possible that obsessing over one’s disqualifications can degenerate to inferiority complex and chronic depression. However, devotional humility is an entirely different ballgame. Within bhakti, we dwell primarily on Krishna, not on our disqualifications. While striving to focus thus, a humble awareness of one’s disqualification becomes the impetus and the launching pad for focusing on Krishna, who is the bestower of ability and mercy. By thus inspiring us to take shelter of the one who is the source of divine empowerment, humility enhances our determination, as is implicit in Srila Prabhupada’s mood in this verse.

- Next he refers to Krishna as the spiritual master of the whole universe, conveying thereby that the Lord knows best how to share his glories with his audience, who are culturally, linguistically, intellectually, religiously and educationally far different from the audiences that he has addressed back in India. Rather than dwelling on such disheartening dissimilarities, Srila Prabhupada focuses on the overarching commonality: Krishna is the benefactor and spiritual master of all living beings, including those that comprise his audience. In service of the supreme spiritual master, Srila Prabhupada is acting as a spiritual master of his audience. He therefore asks the supreme spiritual master to make the servitor spiritual master’s words understandable to the audience – more specifically, he asks Krishna to ornament his words. The ornament he seeks is not poetic beauty, rhetorical flourish or oratory excellence; it is purity of heart, which will make bhagavata-katha not just intelligible to the head, but also transformational for the heart.

- That the ornamentation Srila Prabhupada seeks for his words is purity of intention is evident in the next text. He prays that by Krishna’s mercy, his words will become pure, thereby helping people become free from the miseries caused by their illusions. A physical medicine’s potency doesn’t depend on the motivation of the doctor administering it. The potency of spiritual medicine, however, depends on how purely the speaker is motivated. Put another way, spiritual medicine reaches people’s hearts to the extent the speaker’s heart is pure. The speaker acts as a conduit for Krishna’s omnipotent mercy to flow through; lesser the resistance of self-centered egoistic desires within the conduit, the greater the current of mercy flowing through and reaching the audience. Accordingly, Srila Prabhupada prays that Krishna make his speaking of bhagavata-katha pure. Srila Prabhupada conveys here that he is not relying on the force of his personal charisma or his polemic skills to transform people. No doubt, these played a significant role in the spread of the bhakti tradition under his stewardship. But his appeal conveys that he feels entirely dependent on the potency of bhagavata-katha.

- He then fervently beseeches Krishna: “Make me dance; make me dance, O Master; make me dance like a puppet according to your will.” Here, the intensity of devotional emotion inspires a departure from the symmetry of poetic structure. Whereas all other Bengali verses in this song are duplets, this verse is a triplet, with the third line reinforcing the verse’s emotion with the vivid image of a puppet. The puppet metaphor might seem disturbing, even denigrating. What about human individuality and creativity? Are we meant to reduce ourselves to mere puppets? That bhakti doesn’t require rejection of our individuality and creativity is seen in Srila Prabhupada’s own example. He exhibited remarkable resourcefulness, even ingenuity, in making the bhakti tradition accessible to people in various parts of the world. The thrust of the puppet metaphor is not the rejection of human intelligence but the harmonization of human will with divine will. When we appreciate that Krishna is omniscient and omni-benevolent, we understand that harmonizing with his will represents the perfection of human intelligence. Srila Prabhupada’s appeal to be made a puppet stems from his awareness of both worldly reality and spiritual reality. He is aware of the worldly reality that the task confronting him is formidable, some might consider impossible. But he is not disheartened because his vision is not locked to this world – it extends beyond worldly problems to the spiritual reality of Krishna’s omnipotence, which can overcome all problems. This verse represents a poetic circularity, a satisfying symmetry in the beginning and the end. He begins by stating, “I don’t know why you have brought me here, but you must have some purpose.” And in this penultimate verse he states, “When you have brought me here, please make me dance.”

- Srila Prabhupada concludes by indicating that his honorific “Bhaktivedanta” is not meant to be just a matter of designation – it should be a matter of contribution. Stating humbly that he doesn’t have any knowledge or devotion, he states that he nonetheless has strong faith in the potency of Krishna’s holy name and prays for mercy so that he can live up to the name he has been bestowed. This verse contains the first and only reference to the holy name. The holy name and bhagavata-katha are considered to be non-different. Both are spiritual sound vibrations and both manifest the purifying, elevating, liberating omnipotent grace of Krishna – and Srila Prabhupada seeks Krishna’s mercy in both these manifestations.

History would soon be testimony to how well-placed Srila Prabhupada’s faith was – within a decade, millions the world over started chanting the holy names, hearing bhagavata-katha and discovering the inexhaustible happiness of spiritual love.