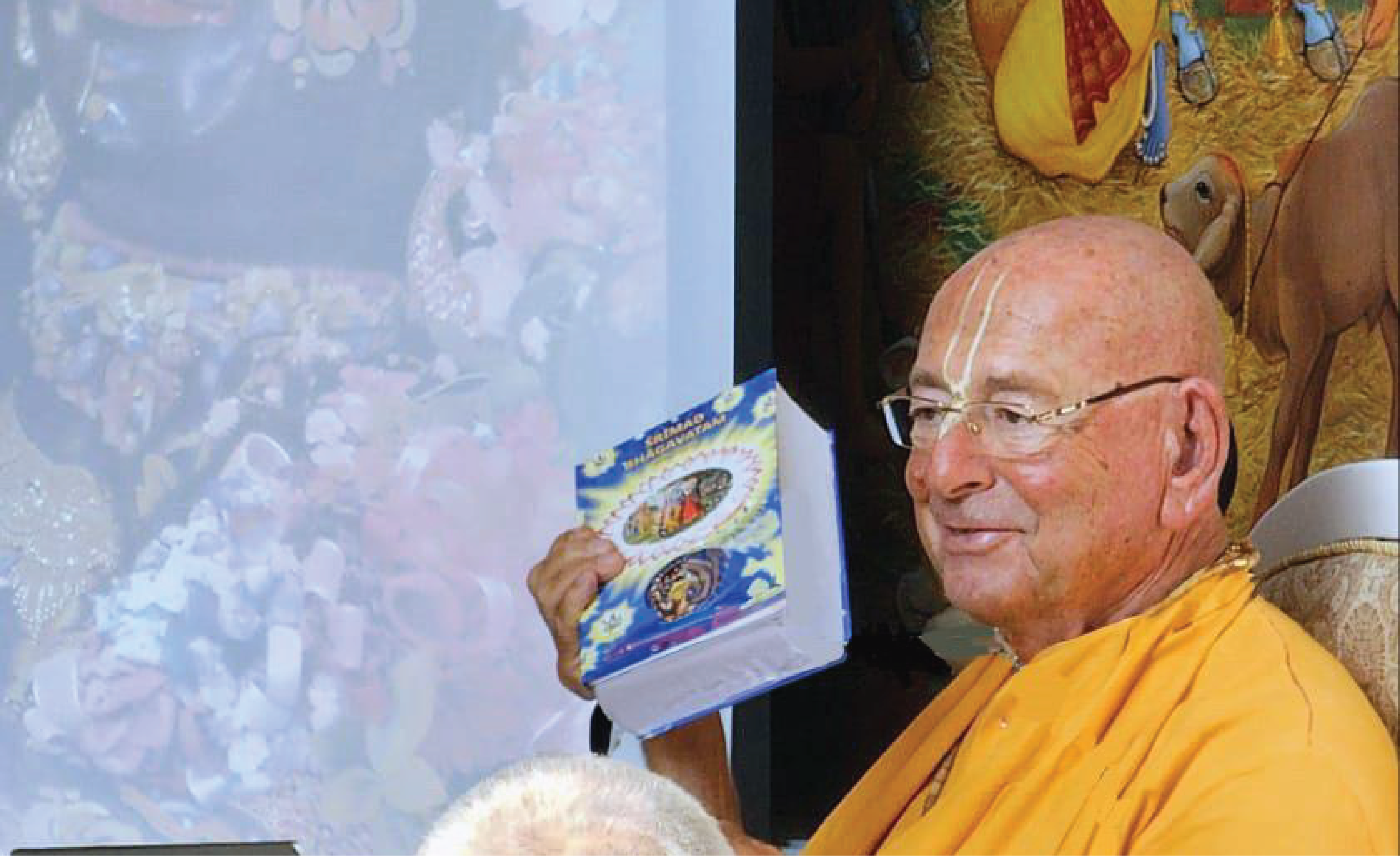

Photographing the Exotic: Brahma Muhurta Dasa

By Madhava Smullen | Sep 27, 2008

The Western eye, and often heart, has always been drawn to the exotic. For artist and photographer Brahma Muhurta Dasa, the pull was stronger than for most. Born Michael Buhler-Rose, he began reading about different philosophies at fourteen, an age when most of his peers were more interested in videogames and girls. When a neighbor of his lent him first Barbara Stoler Miller’s translation of the Bhagavad-gita, and then ISKCON founder Srila Prabhupada’s, he was deeply affected by the ancient text.

“This is it,” he thought. “I want to learn how to follow Krishna’s instructions to Arjuna.” An independent young man, he began visiting his local ISKCON temple in New Jersey, Towaco, and despite protests from his parents, joined at eighteen.

Michael was given the spiritual name Brahma Muhurta by the late Bhakti-Tirtha Swami, and spent many of his early years in the Hare Krishna movement traveling back and forth from the US to India. He utilized his natural inclination for art and detail to dress and worship Radha-Krishna deities, and to research rituals and prepare curriculums at the Bhaktivedanta Academy, ISKCON’s brahmana training school in Mayapur, India.

It wasn’t until several years later that Brahma began to pursue art in a direct way. He received a joint Bachelor of Fine Arts from Tufts University and the Boston Museum School, then got his Master of Fine Arts from the University of Florida in Gainesville. During this time, he realized that photography was the perfect way to express himself. “I was attracted to the unique ability that photography has to describe something,” he says. “There’s this tension that arises between it being a truth-telling device and complete illusion; in many ways, it’s no different than mediums that don’t have anything to do with reality directly, such as painting or drawing.”

Brahma’s career progressed quickly. At the University of Florida, he studied with Andrea Robbins and Matt Becher, a collaborative team whose work had similar parallels to his. They were eager to help Brahma develop his own projects as well as to guide him in his professional art practice. In 2007, he participated in an exhibit at the Art Cologne show in Germany. “It was a very organic process,” he says. “People saw my work there, liked it, and asked if they could exhibit it at another show. And it developed from there.”

Today, Brahma Muhurta’s work has been exhibited in contemporary art galleries in New York, Delhi, Paris, and Italy. Several museums in Germany have his photographs in their collections, and he has upcoming shows in Calcutta and Berlin.

But Brahma’s most striking achievement would come later, inspired by the very exotic that had captured him at fourteen. “I was watching a Bharat-Natyam (traditional Indian dance) troupe run by Anapayini Jakupko, a second generation devotee at the ISKCON temple in Alachua, Florida,” says Brahma, “When an idea suddenly came to me. Here were western women, in Florida, who had been either raised in India or simply born into its socio-religious heritage. They weren’t supposed to be exotic, yet somehow they were.”

Brahma began to recognize scenes that mimicked the orientalist paintings of the French Romantic artist Eugéne Delacroix, and of Paul Gauguin. Some of the photographs that followed drew a parallel relationship to these paintings, while others mimicked them exactly. One of Anapayini and her sister Kumari sitting in front of a pool, for instance, is very similar to Gauguin’s 1891 painting Tahitian Women on the Beach.

But while Gauguin and Delacroix portrayed their subjects only as ‘the exotic other,’ with no identity beyond that, Brahma’s have far more depth.

“At first, the viewers feel familiar with the image, thinking they’re seeing an exotic or Orientalist photograph in the style of the early paintings,” Brahma explains. “But then they’ll do a double-take. Suddenly, they’ll see all the puncture points within the photograph that question the idea of what really is exotic: The Floridian landscape; a Honda in the background; and of course, white American women. But these women are not wearing a costume just to make a point — they have an authentic relationship to the dress. So the viewer has to constantly reassess what is exotic.”

Brahma’s new show, called Constructing the Exotic was exhibited at the University of Florida and at the Southern Illinois University. But it really began to cause a stir this July, when it was featured as part of the Indian-tinged group show Neti-Neti (Not This, Not This) at Bose Pacia gallery in New York. Brahma’s original take on an age-old artistic tradition turned heads and intrigued critics.

“Michael Bühler-Rose’s photographs document young American women whose devotion to Indian culture has led them to adopt the saris, jewelry, makeup and body language of their Indian counterparts,” wrote Roberta Smith in the New York Times. “They seem to have stepped out of Indian miniatures into everyday American settings and send wildly mixed signals.”

While few in the art world truly understood the lifestyle and culture behind these photographs, there were some exceptions. Peter Nagy, the curator of Neti-Neti, is a former East Village art dealer who relocated his gallery, Nature Morte, to New Delhi about eleven years ago. “He’s among the few that appreciate and understand the complex relationship that ISKCON, and especially its second generation, has with India,” says Brahma. “But people who don’t share the same understanding are often moved to ask important questions when they see the photos.”

Questions usually begin with “What is their relationship to India and its culture?” and “How come they’re wearing saris although they’re not Indian?” But these often lead on to deeper inquiries, such as “How does a relationship like this happen?” and “What is the Hare Krishna movement’s philosophy?”

Brahma is not out to convert the art world to Krishna consciousness, but he welcomes such interest, and his projects continue to reflect this attitude.

His next project, like Constructing the Exotic, will also draw from classic paintings – this time, 17th century Dutch still-lifes. “The original paintings were a display of Dutch colonial power, depicting objects which the Dutch East Indian Company had taken from India,” Brahma says. “But today, anything you could buy in a store in Mumbai, Calcutta or Delhi can be bought in the little-India section of most major US cities – and so that’s where I’ll be getting the objects that will feature in my new series, Little Indian Still-Lifes. Thus the series will have the visual quality of Dutch still-life, but will tell the story of India settling in the US rather than of Western colonial power.”

Little Indian Still-Lifes will also probe multiple layers of meaning. “Dutch still-life also had a hidden spiritual side,” Brahma-Muhurta explains. “At the time, religious images were forbidden by the Dutch Reformed Protestant Church. So artists would insert covert symbols to explore spiritual topics. For instance, a watch, skulls, and rotten fruit stood for death; while a flickering candle stood for time.”

Brahma’s exhibit will incorporate similar religious symbolism, albeit with a more Indian flavor. “The candle of Dutch still-life will be replaced by a ghee lamp,” he says, adding that the temporariness of this world is also a major talking point in Vaishnava philosophy. “We’re warned that we must take advantage of what little time we have, because death is just around the corner.”

At only twenty-seven, Brahma’s career is taking off swiftly. This summer, he’ll be curating the shows Opposing Photographers and The Form Itself at New York City’s Bond Street Gallery and Priska C. Juschka Fine Art. Little Indian Still-Lifes will debut in early 2010, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Brahma also focuses on projects more directly connected to ISKCON – he’s currently working on a photographic archive of Krishna’s birthplace, Vrindavana. “Srivatsa Goswami’s institution, the Sri Caitanya Prema Samasthan, hold photos of Vrindavana that go back to the late nineteenth century,” he says. “Using these as a reference, I’ll be looking at Vrindavana’s ancient form, its middle-aged renaissance, and finally the urbanization that began in the seventies and has sadly come to a head within the past ten years. The project will most probably evolve into a large publication featuring all the photos.”

The bulk of Brahma’s photography isn’t so directly connected to Krishna consciousness. Still, he considers it devotional service, since he uses it to support his Krishna conscious family. “I feel that it’s almost offensive to deny your creative inclinations, which are God-given,” he says. “When I wrote an essay for my undergraduate application process, I had to answer the question: ‘Marcel Duchamp, arguably one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, gave up art to play chess later in his career. If you gave up art, what would you do?’”

Brahma’s answer highlights how wonderful Krishna consciousness is. “I did give up art once,” he wrote. “But then I found that to follow the lifestyle I wanted to live, I didn’t have to.”