Review: A Monk’s Quest

By Rrishi Raote | Oct 25, 2009

On a clifftop above the sea, on the Mediterranean island of Crete, a young man meditating at sunset heard a voice inside say “Go to India.” He climbed down to his cave and there met his childhood friend and fellow traveller, who had been meditating on the seashore. This other young man had heard, at the same time, a voice telling him to “Go to Israel.”

Richard Slavin and Gary Liss were middle-class, teenage Americans on a hippie tour of Europe. The 1960s were ending and America was tormented by its war in Vietnam. Slavin, known to his friends presciently as “Monk”, and Liss were not just counterculturals but also serious if unguided spiritual seekers.

The morning after his call to India, Monk left his old friend — and who knew for how long? He had no money and no travel plan. “I believe if I just hitchhike toward the east, someday I’ll reach that land where the answer to my prayers awaits me,” he said. So he did — across Greece, Turkey, Iran and Pakistan.

But he doesn’t reach India until page 86. This marks a change from a number of other books written by Western spiritual seekers in India, which typically get under way once the author is here. Monk’s quest began long before — in his childhood, as he tells it — and he is scrupulous in describing the path he traversed. All this long but fascinating preamble is part of the physical aspect of the “journey home”. The spiritual journey runs alongside.

In India Monk wanders between hills and plains, spending his time with sadhus of all persuasions. He is no tourist but a sadhu himself in search of the right path and the true guru. It is amazing how much seeking he packs into a year — including a month spent meditating on a rock in the Ganga near Haridwar and more time spent in a cave. As in the pre-India section, Monk shows himself to be always open to lessons from experience — and each lesson is marked off in italics to show its importance.

Eventually Monk finds his way to Vrindavan, and there he stays, despite extreme ill health. This place, where Krishna teased the gopis, feels like home.

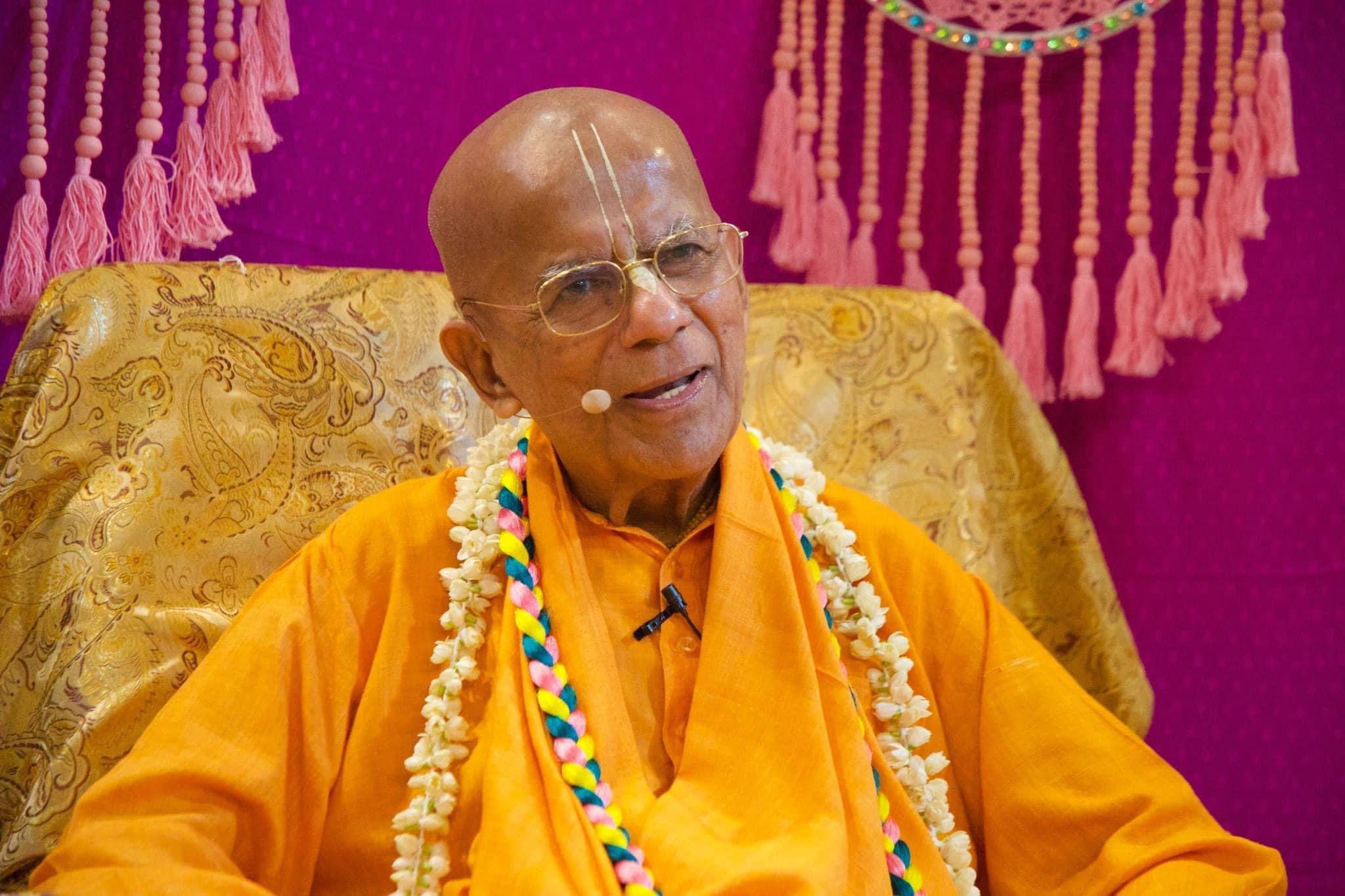

Monk finally takes as his guru Srila Prabhupada, head of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (Iskcon). But this happens at the end of the book. Before this Monk has described the many individuals from whom he sought spiritual leadership, treating each with affection, admiration and sometimes awe. There are memorable characters like the cave-dwelling Tat Walla Baba and the humble Ghanashyam with his cupboard shrine to Radha-Krishna.

Now Monk, or Radhanath Swami, is a senior Iskcon figure. The fact that the end is known makes the story sometimes a trifle dubious — such as the bizarre episode in Kabul when Monk is assailed by a naked Dutch temptress (“perfumed”) and her sweaty Afghan bodyguard, akin to Jesus’s temptations in the desert. But as a whole, the uncomplicatedness and insider-hood of the telling should abash anyone who sees in this book any hint of that evil affliction, Orientalism.