Violence in India Fueled by Religious and Economic Divide

By Hari Kumar and Heather Timmons | Sep 06, 2008

TIANGIA, India: Those who came to attack Christians here early last week set their trap well, residents say.

First, they built makeshift barricades of trees and small boulders along the roads leading into this village, surrounded by rice fields and mango trees, apparently to stop the police from intervening.

Then, villagers say, the attackers went on a rampage. Chanting “Kill these pigs” and “All Hindus are brothers,” the mob began breaking into homes that displayed posters of Jesus, stealing valuables and eventually burning the buildings. When they found residents who had not fled to the nearby jungle fast enough, they beat them with sticks or maimed them with axes and left them to die.

A local official said three people died as a result of the attack on Aug. 25. The carefully placed roadblocks accomplished their purpose; residents say a full day passed before help arrived.

The scene in Tiangia was repeated in villages throughout the Kandhamal district and several other areas of Orissa, a remote and destitute state in eastern India, eyewitnesses and the police said. The violence, which left at least 16 dead, was among the worst in decades against Christians in this Hindu-dominated nation and appears to have been fueled, at least in part, by the growing gap between India’s haves and have-nots.

Orissa has long suffered from government neglect, and Christian missionaries provide services, including schooling, much better than most residents receive, if they receive any at all. While that has caused discontent before, the stakes are growing in a country where the well-educated have a better chance of joining the economic boom.

The attacks in Kandhamal have destroyed or damaged about 1,400 homes of Christians and at least 80 churches and small prayer houses, which were set on fire, a local government official said. Clergymen say orphanages were also destroyed. Estimates from Christian groups put the death toll at more than 25, though a state official in Orissa said 16 were killed.

“I am afraid and will not go back to my village,” said Asha Lata Nayak, 25, who took shelter in a crowded relief camp in Raikia. She is among an estimated 13,500 people who have fled to refugee camps, according to Krishna Kumar, the top state official in Kandhamal.

Nayak says that her husband, Bikram, was fatally wounded while she hid and that her house was destroyed. She said three of the attackers were neighbors.

The violence in Orissa continued this week. An additional 10 prayer halls and a convent were torched on Monday, local and national news media reported, and the federal government pledged Tuesday to send more paramilitary troops to the area to reinforce the local police; in Kandhamal, more than 3,000 troops have arrived.

But on Wednesday, India’s Supreme Court ordered Orissa’s government to submit a report about how it is controlling the area, after reports by Christians that police were not doing enough to stop attacks.

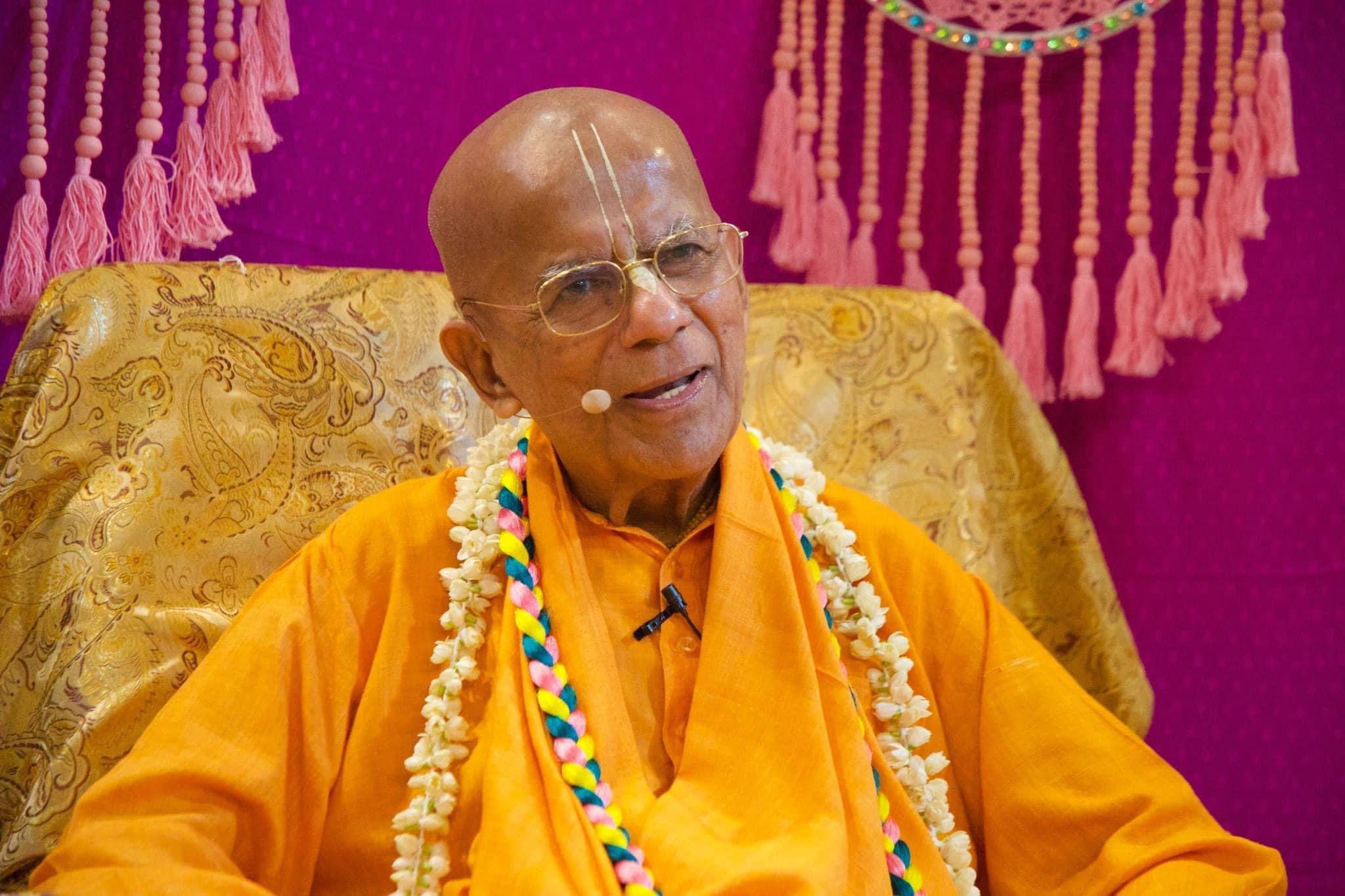

The violence was prompted by the Aug. 23 murder in Orissa of Laxmanananda Saraswati, who had been associated with a Hindu radical group opposed to fellow Hindus’ converting to Christianity. Although a letter left at the scene claimed that Maoist rebels carried out the attacks, many Hindus blame Christians instead.

Non-Christians have long resented the conversions — the most recent Indian census, in 2001, states that 2.3 percent of the population is Christian — but tensions have increased as India’s economy has taken off.

Christian missionaries in India have focused on indigenous and lower-caste groups, including untouchables, or Dalits. Despite laws dating almost to Indian independence in 1947, Dalits are often discriminated against or worse. They are sometimes barred from basic amenities, relegated to dirty and hazardous jobs, and beaten, raped or killed because of their social status.

Conversion to Islam or Christianity does not erase caste identity completely, but Christian missionaries and other non-Hindu religions offer a possible escape by providing Dalits and other downtrodden groups with education, including English classes. Fluency is crucial for anyone who wants to join India’s booming service businesses, including hotels, or to break into the information technology industry fueling much of the country’s growth.

“Across India today, the disenfranchised and repressed peoples, the tribes and the low castes are exiting the caste system” that is entrenched in the Hindu religion, said Joseph D’souza, the president of the All Indian Christian Council and an advocate for Dalit rights. They are converting not only to Christianity, he said, but to Buddhism, Islam and Marxist atheism.

“People are in revolt” after 60 years of their rights being trampled, he said, adding, “It has nothing to do with any particular religion.”

But the conversions occur as many in India’s rural areas, including Kandhamal, see themselves as left behind economically. The area’s 650,000 people subsist mainly by growing and selling rice, turmeric, ginger and forest products.

“The conflict is increasing because we are trying to educate the people and enlighten them,” said Pastor Thomas Varghese, 56, in an interview in Raikia, where he has lived for 10 years. He said he ran almost two miles and spent a night in the jungle to save his life last week, after a mob that included nine people he recognized tried to kill him.

But Pramod Pradhan, a young Hindu farmer in Tiangia village, views the conversions differently, and echoed the feelings of many of the state’s Hindus. “Christian missionaries lured Hindus to convert to Christianity. They bring lot of money to do that.”

Padma Charan Panda, an upper-caste Hindu and a turmeric trader who was watching a televised debate on the issue in Raikia, said “Christian traders exploit poor and illiterate” people.

Meanwhile in Tiangia, Bikram Nayak’s motorcycle lay burnt outside his badly damaged home, where rains had poured in through the roof. Nayak, 30, a government kerosene salesman, died from head wounds after being severely beaten by the mob , his wife said.

Nayak said her faith in Christianity remained unshaken. “My husband died for God Christ,” she said. “I was born as a Christian and I will die as a Christian.”

Hari Kumar reported from Tiangia, and Heather Timmons from New Delhi.