ISKCON Scholar Speaks On Link Between Mental and Spiritual Health

By Madhava Smullen | Apr 14, 2012

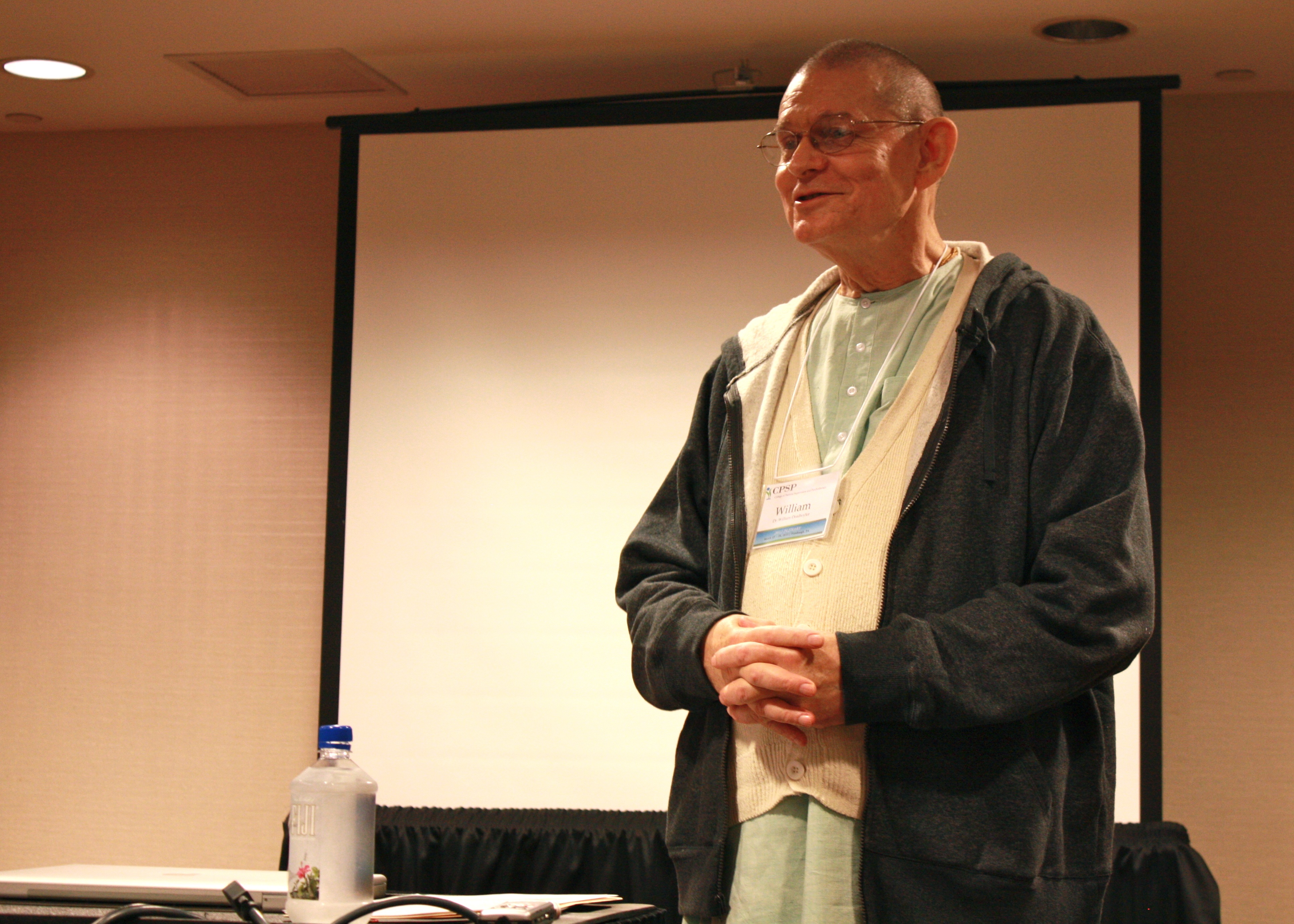

Addressing an audience of around forty, ISKCON scholar Ravindra Svarupa Dasa spoke on the connection between mental and spiritual health at the annual conference of the College of Pastoral Supervision and Psychotherapy on March 25th.

The conference, held at the Doubletree hotel in downtown Pittsburgh, was a major event for clinical pastoral educators—those who train and certify chaplains in preparation for serving at mental institutions, hospitals, hospices, and prisons.

In his talk, entitled “On Continuing the Project of Anton T. Boisen’s Constructive Synthesis: A Contribution from a Vaishnava Hindu Tradition,” Ravindra Svarupa, speaking in full Vaishnava robes, discussed the impact the work of Anton Boisen, a pioneer in clinical pastoral education, had on himself and the ISKCON organization.

Boisen was a Christian minister who was diagnosed with scizhophrenia in 1920 at the age of 44, and placed in Westboro State Mental Hospital by his family. Doctors said he would never recover.

But fifteen months later, he recovered. And as he did, Boisen realized that his condition had been brought about by an extreme spiritual crisis; and that while some of the other patients at the hospital had organically-based illnesses, many suffered from conditions similar to his.

When he was released from hospital, Boisen had a new mission. He began to study the psychology of religion, and developed the thesis that a spiritual crisis can go two ways: if the outcome is successful, it’s called a religious experience. But if the individual’s condition deteriorates, it becomes known as a mental illness.

Eager to test out his ideas scientifically, Boisen became a chaplain in a mental hospital, so that he could understand and help mental patients. Eventually, he began to train future chaplains and became a pioneer in clinical pastoral education. He also wrote several books.

During his talk at the College of Pastoral Supervision and Psychotherapy, Ravindra Svarupa told an intrigued audience of mostly Christian ministers that in 1988, while ISKCON was going through serious struggles, he had overheard a devotee at a “Sunday Feast” program discussing Boisen’s book Exploration of the Inner World.

Ravindra searched high and low for the out-of-print volume, and finally found it at a used bookstore. “Boisen’s parish work and work with the mentally ill was based on Midwestern American Protestant Christians in the 1920s and ’30,” he says. “But the amazing thing was, despite coming from a vastly different geographical and cultural background, his book was a map of the Hare Krishna Movement’s struggles and difficulties in the 1980s.”

Not only was Boisen’s work useful in helping ISKCON’s problems, but it was also congruent with Srila Prabhupada’s teachings: Boisen thought of spiritual life as a science not dependent on historical tradition, and of human beings as being spiritual by their very nature.

Although Ravindra Svarupa was at first hesitant to use something outside the Vaishnava tradition, Boisen’s work was too good to pass up. So in 1996, he gave a month-long class on it called “The Cure of Souls in Vaishnava Communities,” at the Vaishnava Institute for Higher Education in Vrindavana, India. He followed this up with shorter versions of the same course for ISKCON devotees in Radhadesh, Belgium, and Moscow, Russia in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Finally, this year, psychiatrist Robert Charles Powell, MD, PhD, who helped start the College of Pastoral Supervision and Psychotherapy and continues to be one of its advisors, learned of Ravindra Svarupa’s work. He invited the ISKCON scholar to speak at the organization’s annual conference.

In his talk at the conference, Ravindra Svarupa spoke on Boisen’s ideas about what is good for spiritual life, and what is not; and how these ideas corresponded with Vaishnava concepts, especially that of the three modes of material nature.

He discussed how, at the center of Boisen’s 1936 work The Exploration of the Inner World, there is a chart entitled “Personality Changes and Upheavals Arising Out of the Sense of Personal Failure.”

“According to Boisen, the central problem in spiritual health is a sense of personal failure, a common characteristic in religious organizations with high demands and ideals,” says Ravindra Svarupa. “In ISKCON, for example, the ideal is the pure devotee. In the early days, especially, we were expected to join the temple, surrender, and act like a pure devotee right away. We have what Boisen calls ‘desire for response and recognition’: we want to be accepted by personalities like Srila Prabhupada or the Six Goswamis as members of their group. And with that ideal, we look at ourselves, think wow, look at where I am, and feel like we’ve failed.”

There are different responses to this common feeling of personal failure. At the bottom, are the responses in the mode of ignorance, or what Boisen classifies as a degree of awareness known as “Oblivion.” These include withdrawal from the association of devotees or fellow spiritualists, social isolation, and surrender to all one’s lowest impulses. They end in “progressive disintegration” as Boisen calls it in his chart—essentially, mental illness.

In the middle of the chart are responses to the idea of personal failure in the mode of passion, or the degree of awareness Boisen calls “confused.”

Responses in this mode tend to come from concealment. For example, a devotee who is aspiring towards pure devotion may feel conflicting material desires, which is a perfectly natural and common experience. Yet in the “confused” mode he may still want to be known as a great devotee, and thus respond by concealing the truth.

Sometimes this reflects a problem in the institutional attitude, rather than with the individual.

“Say someone is a brand new devotee, and having normal problems with the regulative principles,” Ravindra Svarupa explains. “And he expresses that to another person, who responds, ‘Well that means you’re not a devotee.’ He’s never going to say anything again after that! He won’t talk about his real problems or issues, because he’s afraid of being condemned. That’s concealment.”

Symptoms of concealment include faultfinding, which, when it deteriorates, can turn into paranoia, a kind of mental illness.

“If you secretly feel guilty about yourself, then it’s a relief to look at everyone else as bad, too,” Ravindra Svarupa says. “To give an example from the Vaishnava text Chaitanya Charitamrita, Ramachandra Puri, a disciple of Madhavendra Puri, failed in his relationship with his guru, and so began to criticize others, saying, ‘I see that the disciples of Chaitanya eat too much.’”

Variations of faultfinding, according to Boisen, include substituting minor virtues for major ones. “You fail at the major virtue, so you elevate a small ritual as the important thing,” Ravindra Svarupa explains. “For example, ‘Oh look at all these people, every time they bow down, they let their bead bags touch the floor. That’s awful!’”

Another variation is shifting responsibility, either to other people or to organic scapegoats. For example: “The reason I don’t chant sixteen rounds a day is because there are no pure devotees in ISKCON.” Or “The reason I don’t chant is because I have this disease, or that problem.” Yet another variation is making light of accepted standards—every religion has its “Catholic priest” or its “pure devotee” jokes.

“Another result of concealment is diversion,” says Ravindra Svarupa. “For example: ‘I’m a really good kirtan singer, or fundraiser, and even though I don’t follow the regulative principles, my talent is what really counts because it inspires so many people—so I must not be as bad as I seem to myself.’ And yet another result, of course, is to lower the standards. We say things like, ‘Srila Prabhupada didn’t really mean this—what he meant was this.’”

Moving on up to the top of Boisen’s chart, we find responses to the ‘personal failure’ problem in the mode of goodness, or what Boisen calls the “clear” degree of awareness. These are the ones that are healthy and necessary for spiritual progress.

“Even advanced devotees don’t think they’re advanced,” Ravindra Svarupa says. “But there’s a healthy way to deal with it. Rather than concealment, there is what Boisen calls ‘frankness’ and what Vaishnava texts call saralata, or simplicity. Just being frank and honest about where you are with yourself and others. And with that comes genuine humility.”

Srila Prabhupada talks about this too. “Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura comments that saralata, or simplicity, is the first qualification of a Vaishnava, whereas duplicity or cunning behavior is a great offense against the principles of devotional service,” he writes in the Antya lila of Sri Chaitanya Charitamrita. “As one advances in Krishna consciousness, one must gradually become disgusted with material attachment and thus become more and more attached to the service of the Lord. If one is not factually detached from material activities but still proclaims himself advanced in devotional service, he is cheating. No one will be happy to see such behavior.”

Going together with this is Boisen’s idea to have a dynamic, rather than a static view of morality.

“Dynamic means that anyone who is seriously trying to improve themselves is good,” Ravindra Svarupa says. “Rather than condemning others or ourselves, we look for how we can deal with the problem in productive ways, so it gradually gets better. That’s just the healthy way of doing things!”

All of these insights were greatly appreciated by the ISKCON audiences Ravindra Svarupa taught his course to, as well as the ministers attending his one-hour talk at the annual conference of the College of Pastoral Supervision and Psychotherapy. Several of them approached him afterwards, while one wanted to know how to get a copy of the books he’d mentioned, Bhagavad-gita As It Is and Sri Isopanisad.

“This group is dedicated to working with all kinds of religious traditions, and so they were hapy to see somebody from the Dharmic faiths, if you will,” Ravindra Svarupa says. “I felt very welcome, and I think that we’ll keep up a connection.”

One of the ways Ravindra hopes to do this is by working with with the College, Dr. Robert Powell, and ISKCON organizations such as Mumbai’s Bhaktivedanta Hospital to establish clinical pastoral training and education within ISKCON.

“I think it’s a big opportunity for devotees to become certified chaplains for hospitals, prisons and the like,” says Ravindra Svarupa. “And to help both ourselves and the general public, and spread Krishna consciousness in the broadest way possible—not as a sectarian faith, but as a spiritual science. We hope to also get our own hospices and hospitals in America, just like we have in India. Devotees would be happy to work in such a career, and I think it’s an excellent way for us to become more integrated with society.”