Reversing the Secularization of Eating

By Kent Hayden, M.Div. | Oct 21, 2010

At the end of a journeyman’s summer, I lay in an unfamiliar wood, watching the stars assert themselves upon a deepening night. My wanderlust faded into a gentle homesickness, and I dreamt of cookies, warm chocolate chip cookies and coffee, the deepest of comforts from my Christmases and homecomings. I flipped through the remembered textures and smells of soft dough and chocolate, and I was struck by the centrality of food to my story. Eating has marked my celebrations and my tragedies. Its rituals surround and define the points of reference by which I know my life, and from which I collect hints of life’s meaning.

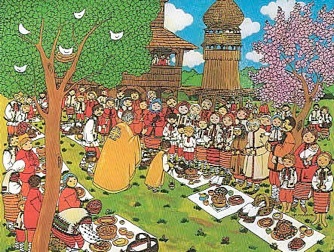

I imagine that such an association with eating is, or has been, the norm for most of us. Across cultures and traditions, the cycles of gathering, preparing, and consuming food have been occasions of ritual and storytelling. They have led to a series of practices and beliefs that ground people in their social, environmental, and existential contexts. But these connections are fading as our eating loses its grasp upon what sacred moments we have left.

Our ancestors indwelled a world flush with the sacrosanct. Hunters connected with their prey as a part of a single chain. They spoke to the spirit of the slain animal and respected its sacrifice. Farmers tended an order that both depended upon and sustained them. They danced and sang for the rain and acknowledged their place in the cycles of nature. Cooking was sanctified as communities grew and defined themselves in terms of their diets. Laws and rituals were developed to bind people together through food. And the final act of eating was sanctified as sustenance was passed between the work-rough hands that contributed to its production. Prayers were spoken and bread was broken as friends and families fed their living with a sense of gratitude.

As these relationships and connections began to be displaced by considerations of utility and efficiency, the sacred was squeezed out of our food system from the outside in. Scanning cartoon-faced packages and dropping cold-cuts into a basket is rarely occasioned with reflection upon one’s place in the universe. The commodification of our eating eliminated the empathy between consumers and consumed. Chemically nurtured and internationally distributed monocropping robbed farmers of their connection with the rhythms of the soil and their relationship with their customers. Mass-produced and nutritionally bankrupt diets broke the social ties of traditional cuisine. And the subjugation of meal-time to our commutes and our sitcoms eliminated the occasion for reflection upon and gratitude for the simple good of enjoying our food.

Our eating has been secularized. It has been robbed of its poetry and beaten into the staccato uniformity of packaged snacks. We have insisted upon efficiency as the only criterion of our culinary aesthetic. As a direct result, our prey suffer needlessly, our planet is wilting under the pressures of our demands, our neighbors are strangers, we are unhealthy, and our place in the order of things is lost behind the incessant pace of our living.

We are in desperate need of reconnecting our eating with the sacred. This needn’t mean a return to the perspectives and practices of the past. It does necessarily mean a reevaluation of the fundamental principles by which we relate to our eating. It means including considerations of beauty and meaning in the design of our food systems.

Conveniently, our religious traditions are equipped with tools and traditions for just such a reconsideration. Ramadan, Yom Kippur, the Sabbath, and the Eucharist — all opportunities for exploring and restoring connections between the sacred and our eating.

But to take advantage of this shared concern for sacred eating, we must be willing to crack open the shells that have formed around our rituals and allow them to inform our everyday living. They must be set loose on our reality so that our memories of warm cookies and coffee continue to bind together not only our own narratives, but our communities, our planet, and the thousand little relationships out of which the sacred emerges.

Kent Hayden, M.Div., is a recent graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary. His exploits include used book hunting, organic vegetable farming, and thought gathering. He is based in New Jersey but is currently living and writing in Royal City, WA.